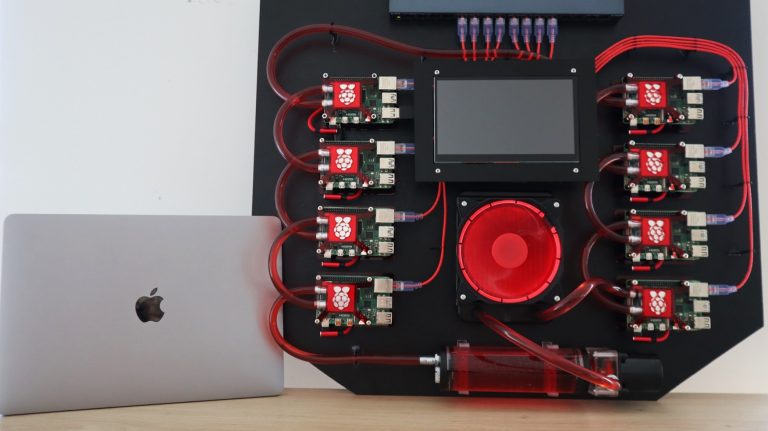

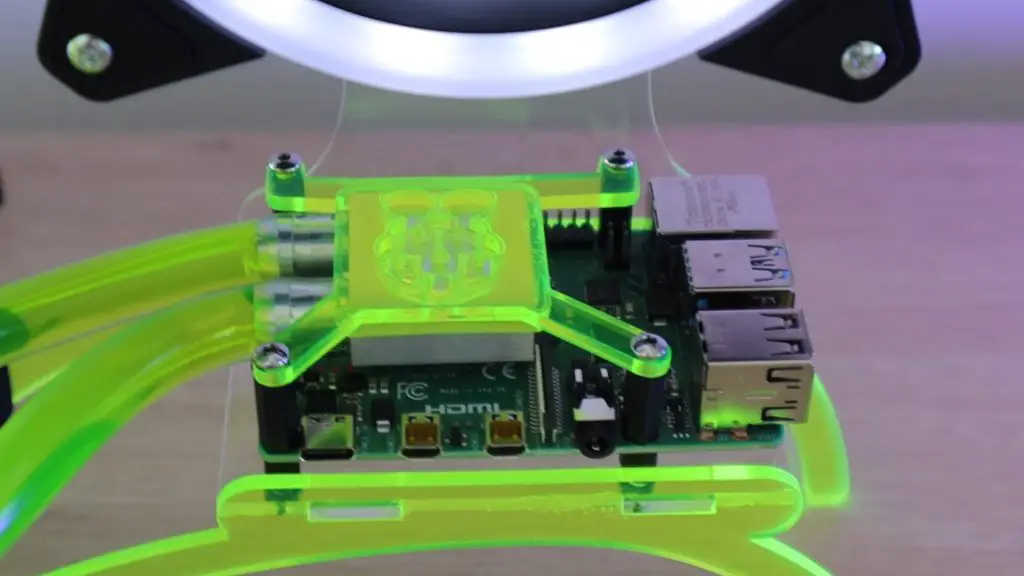

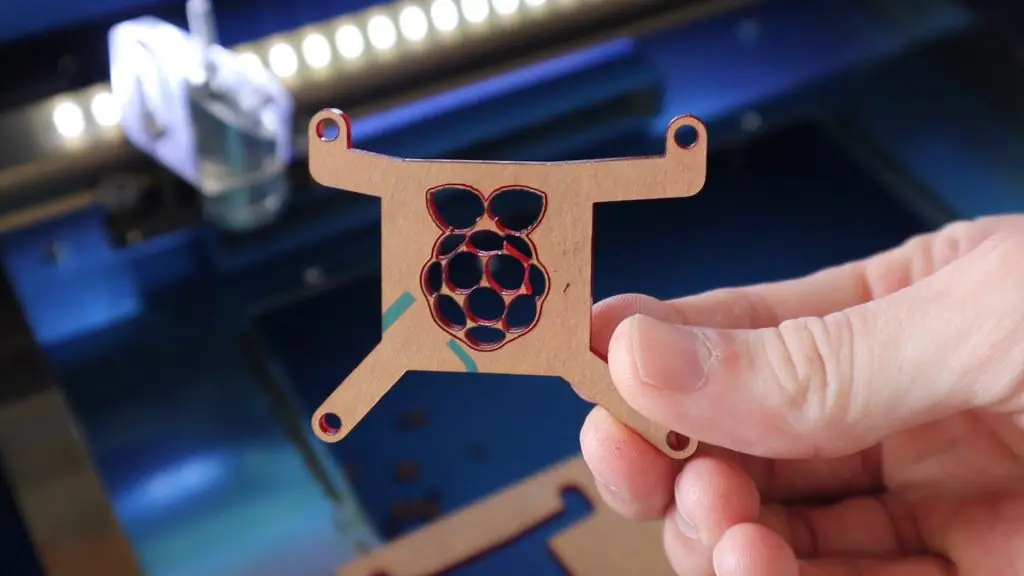

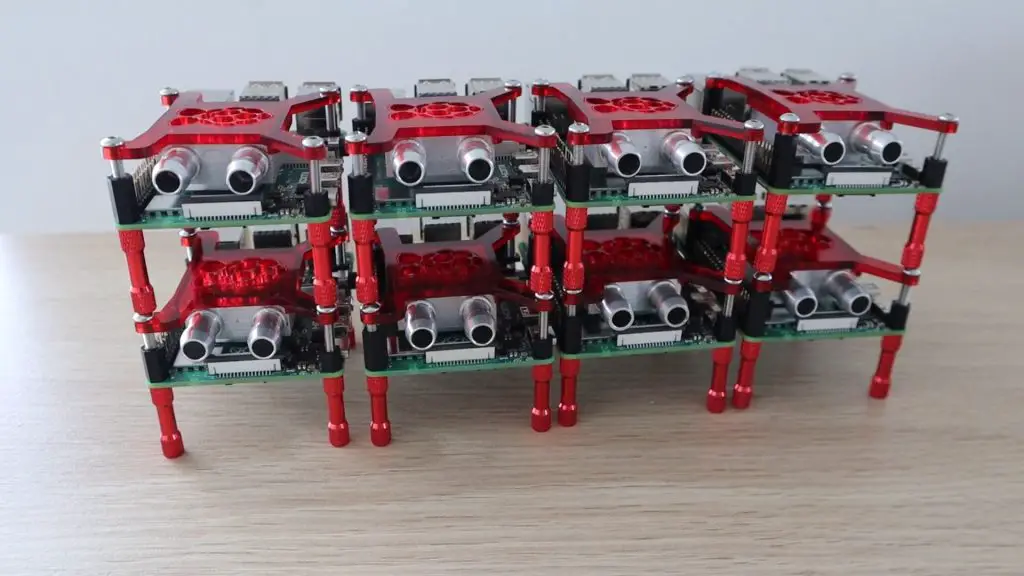

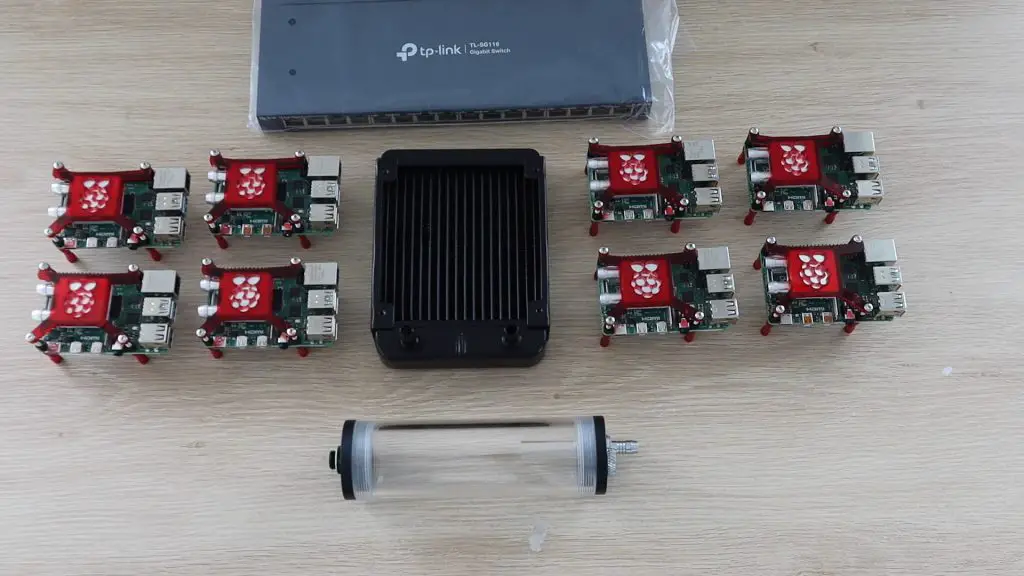

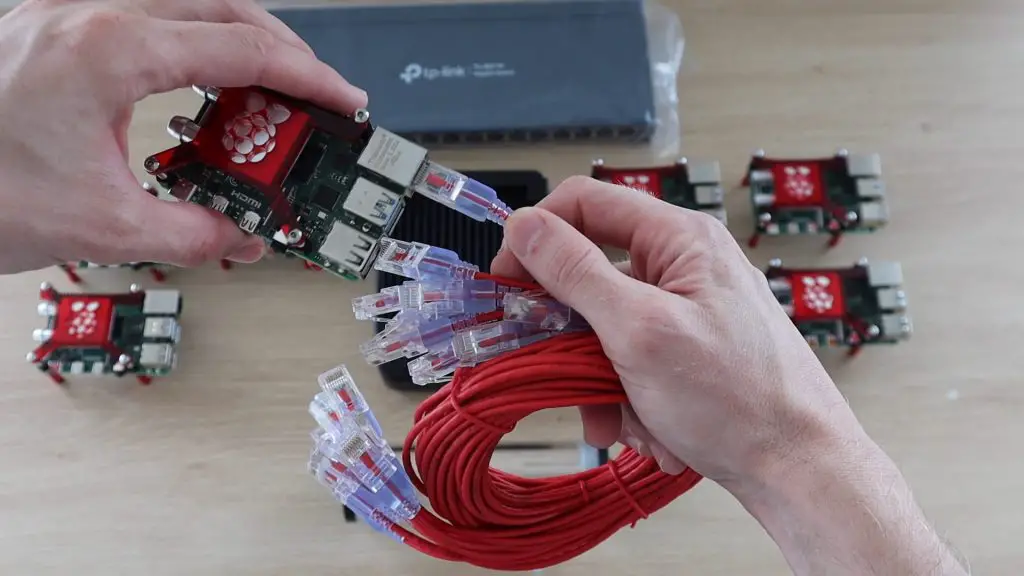

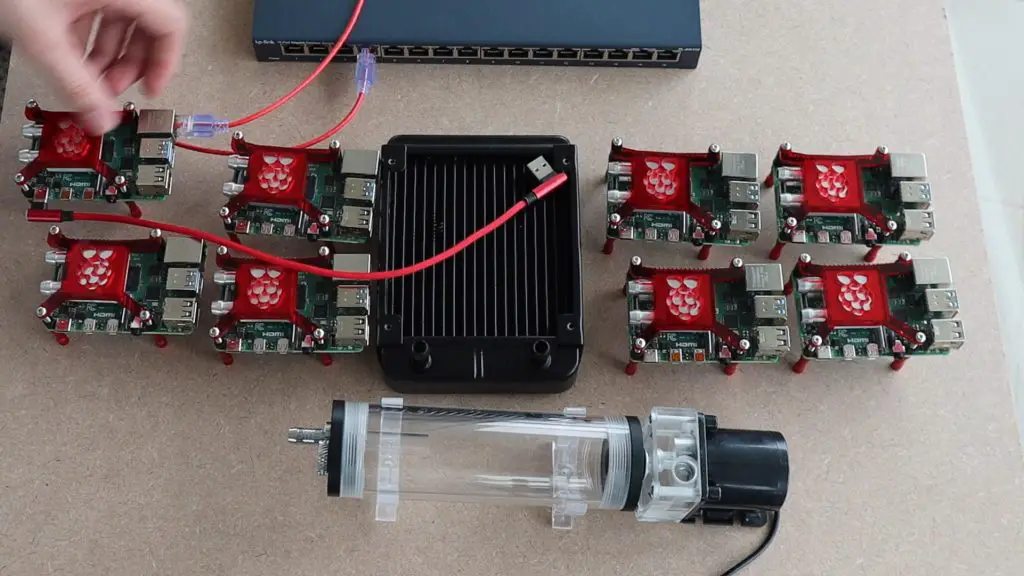

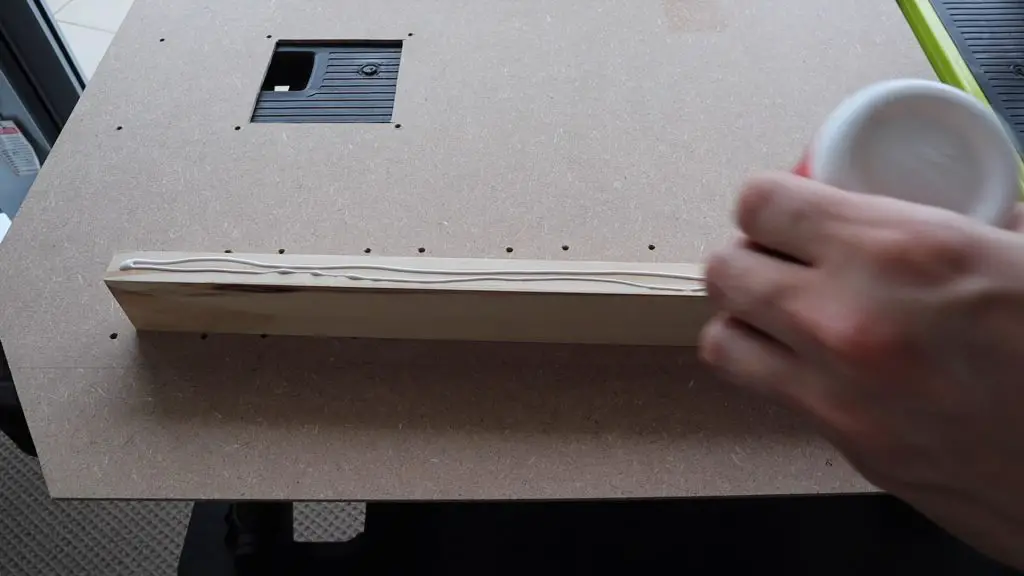

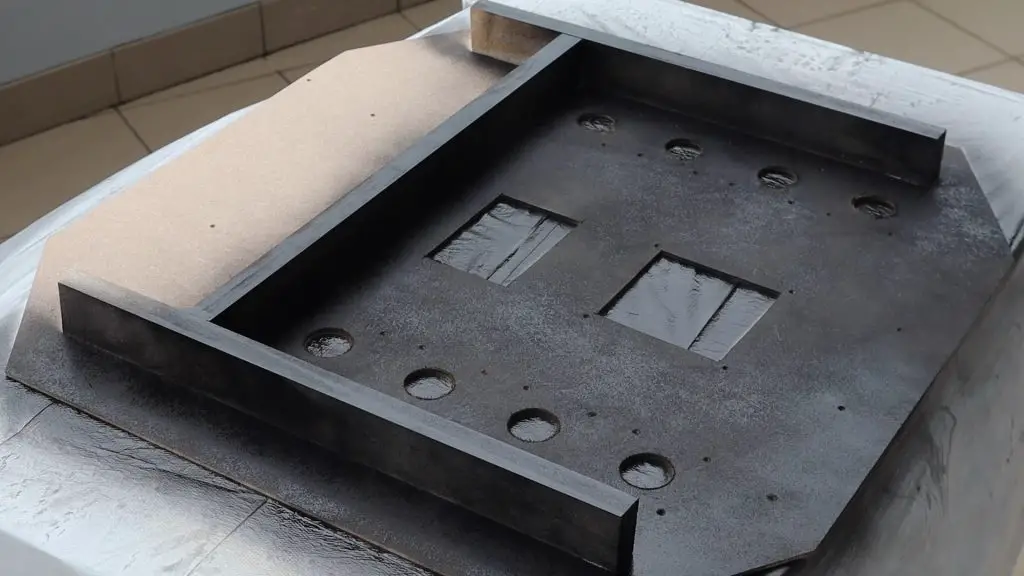

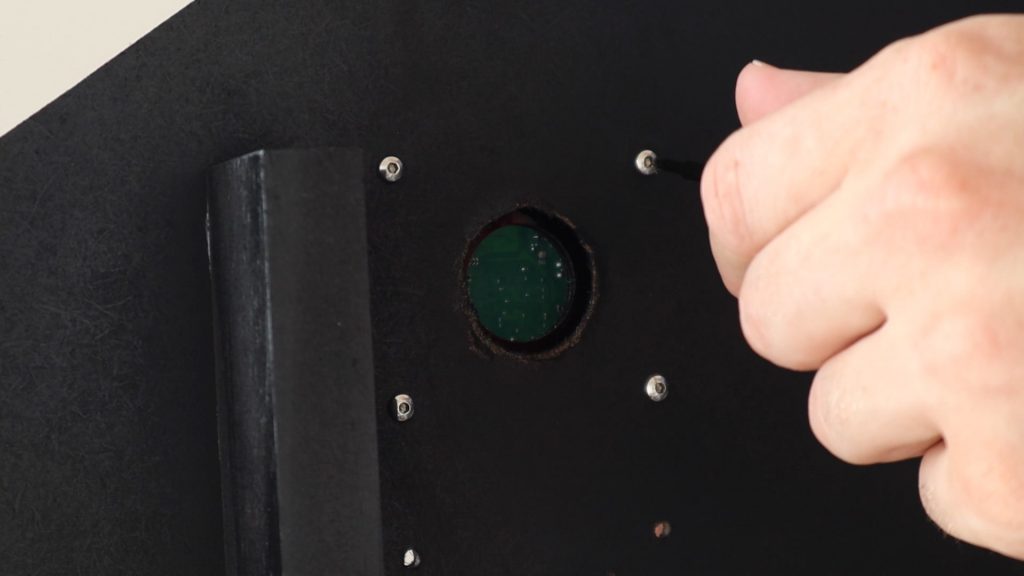

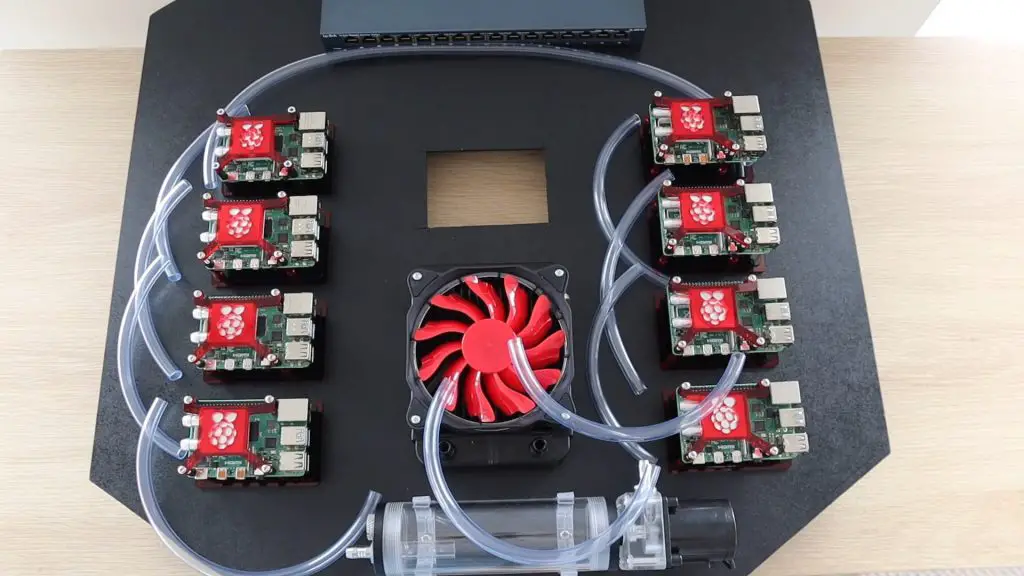

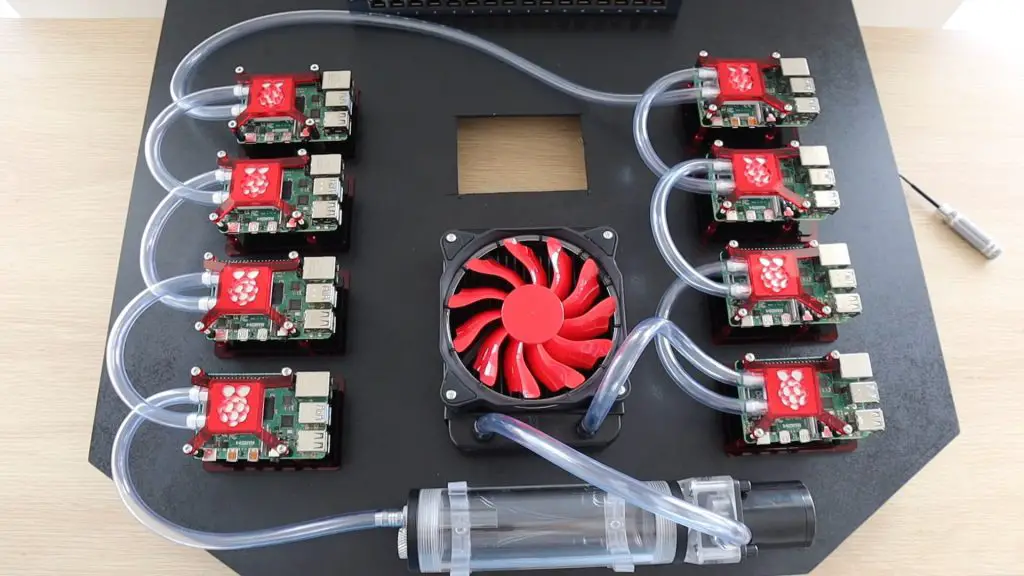

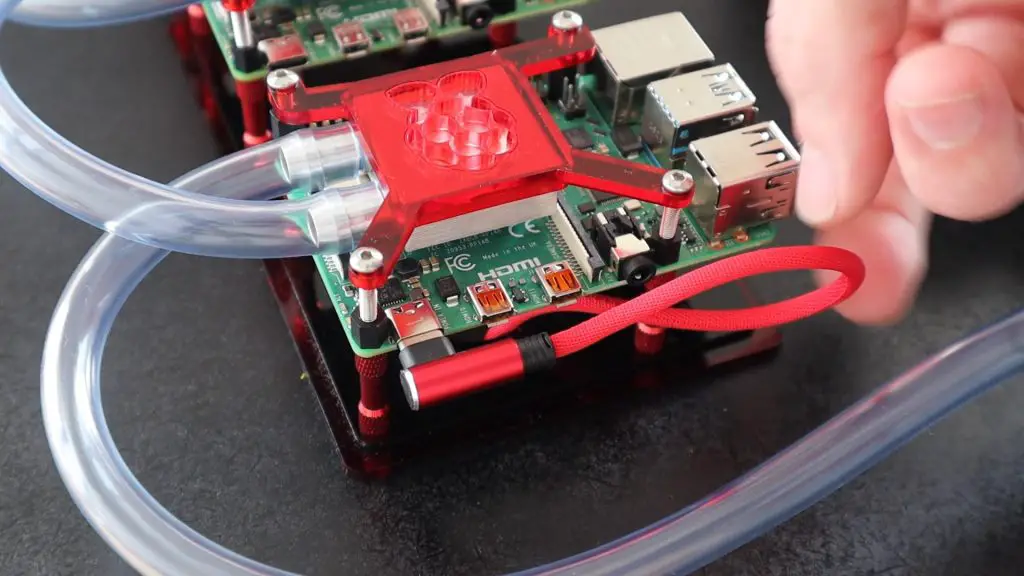

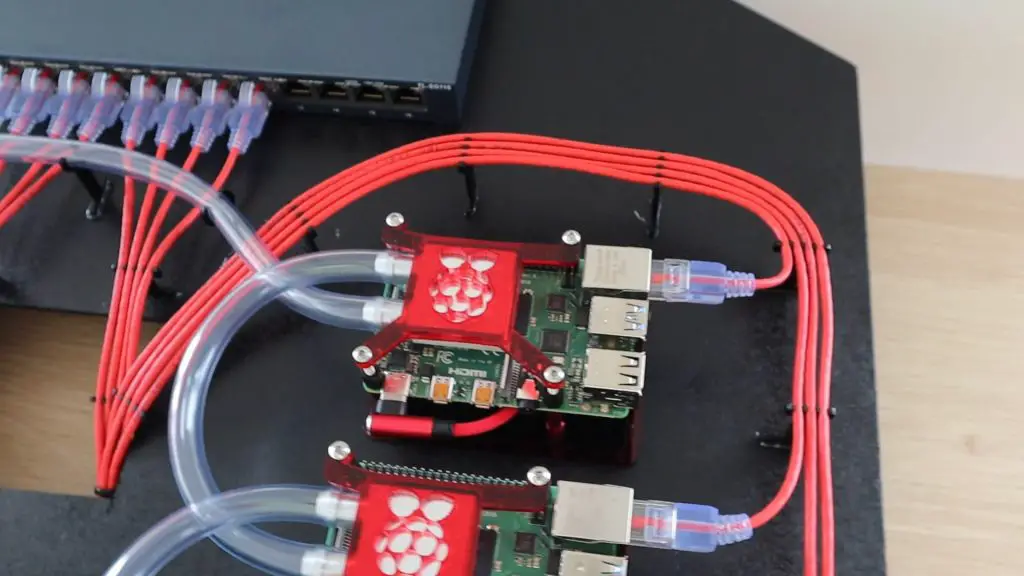

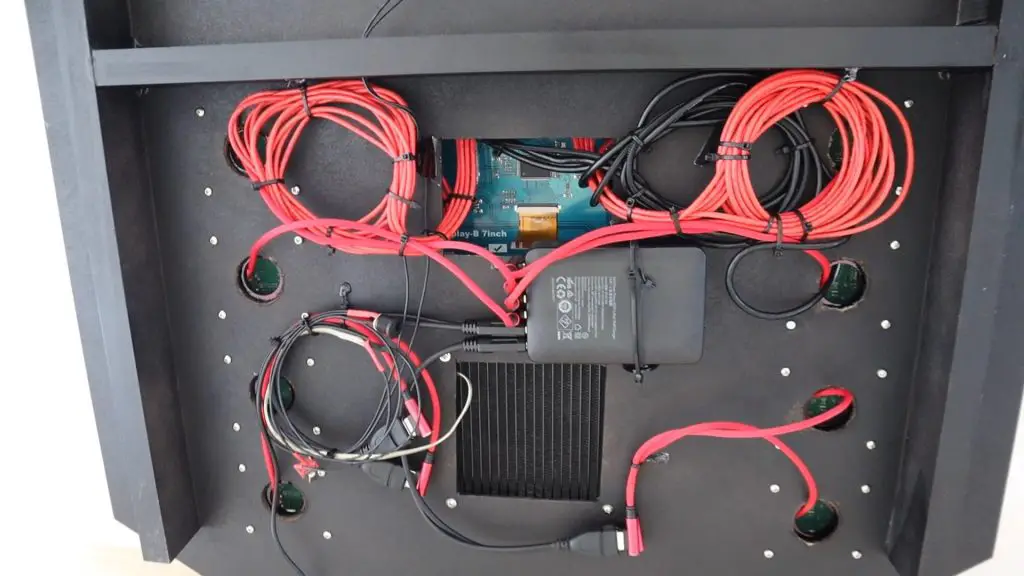

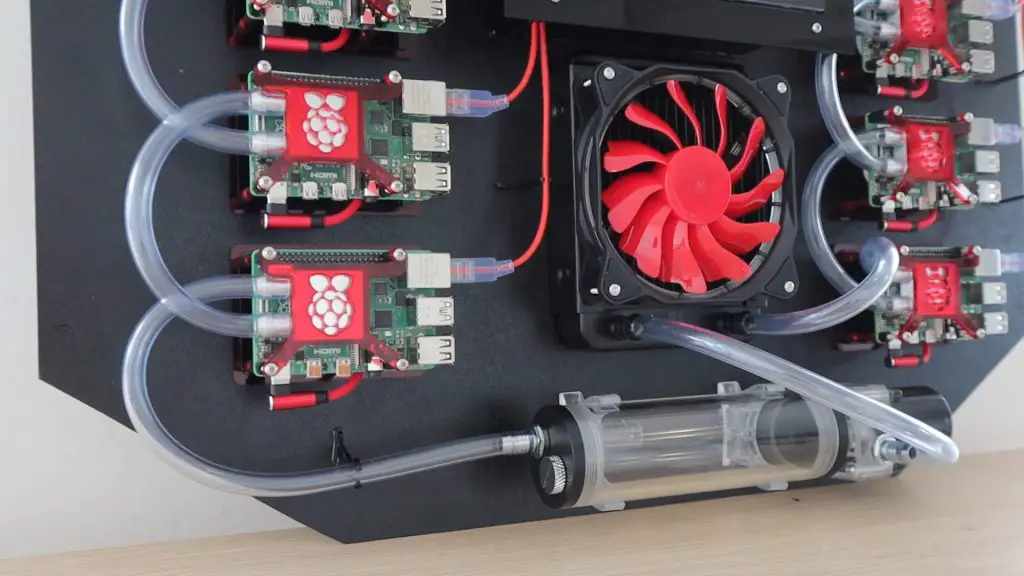

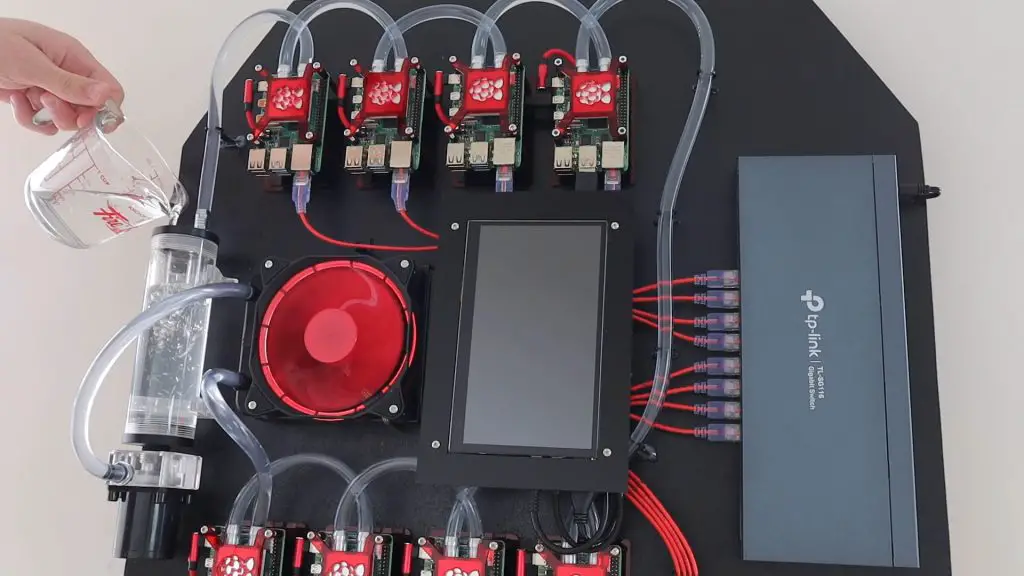

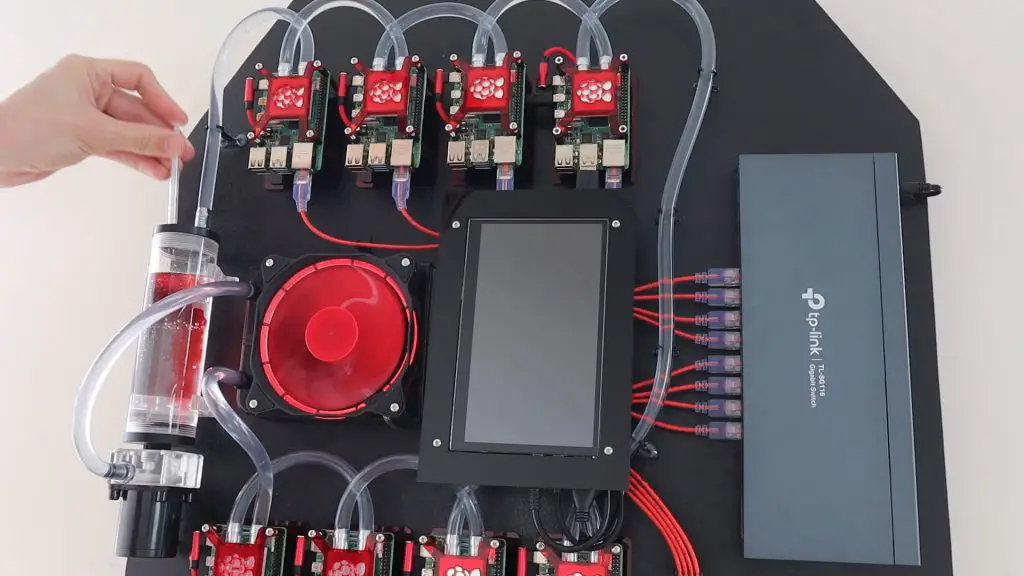

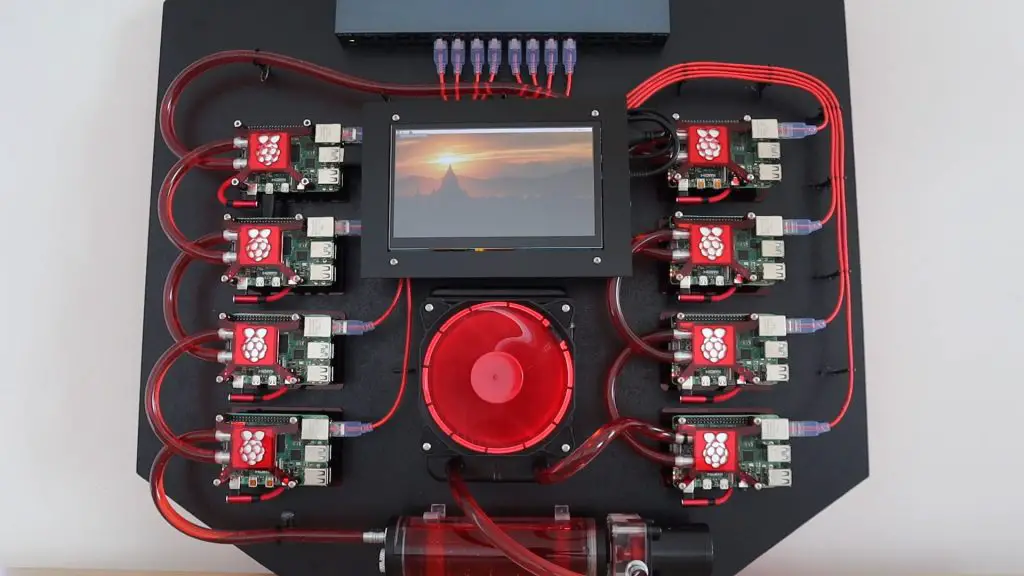

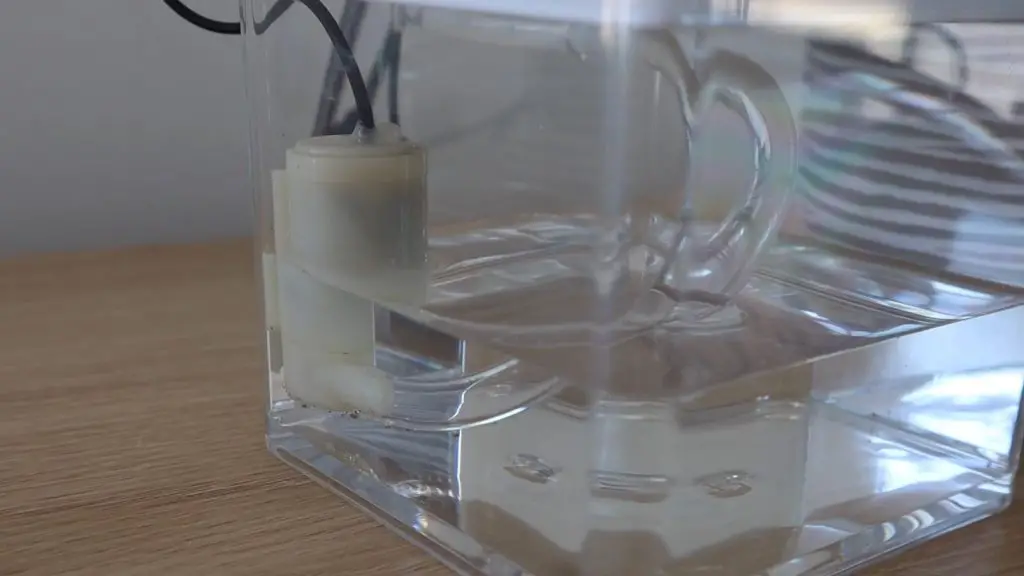

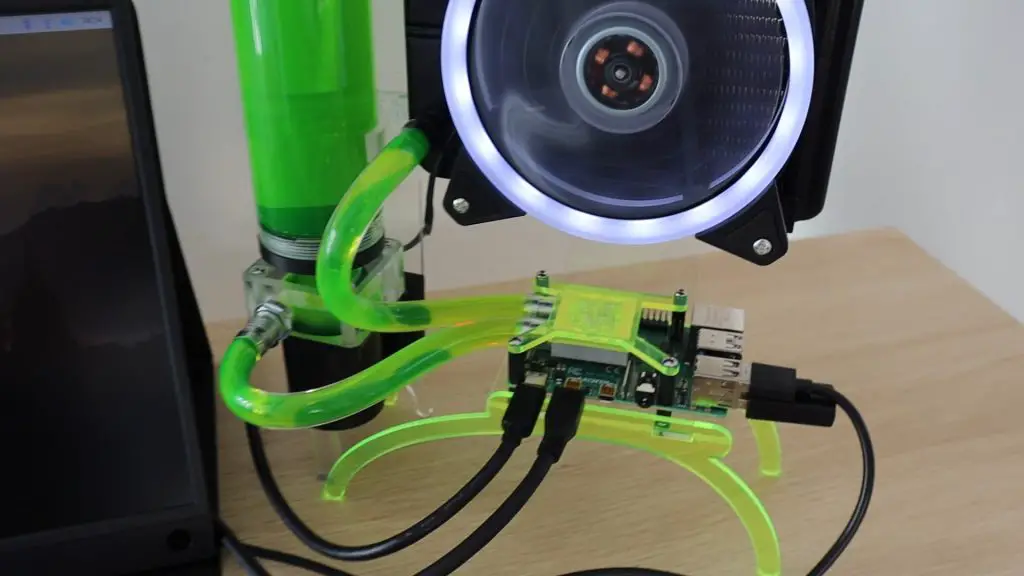

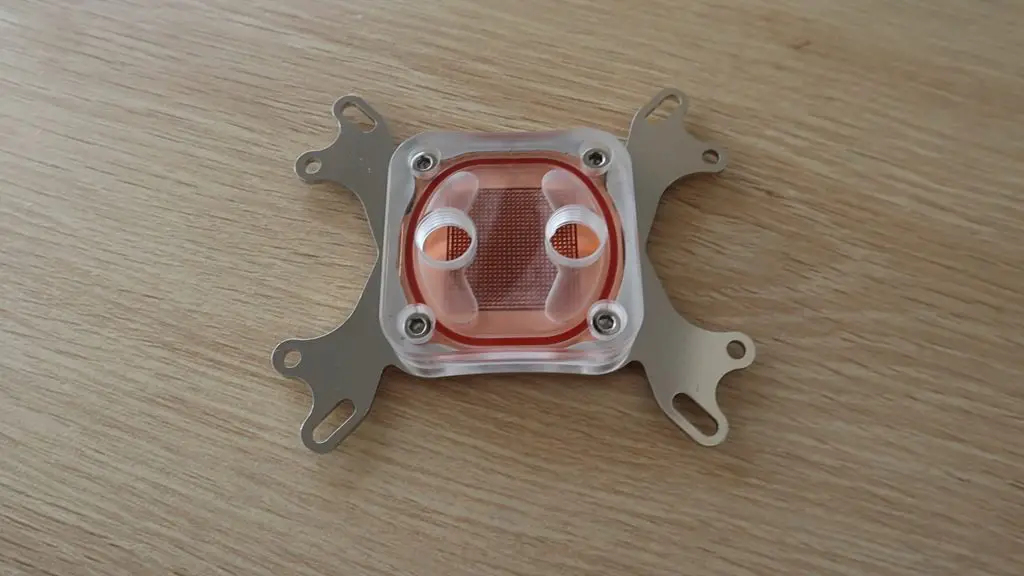

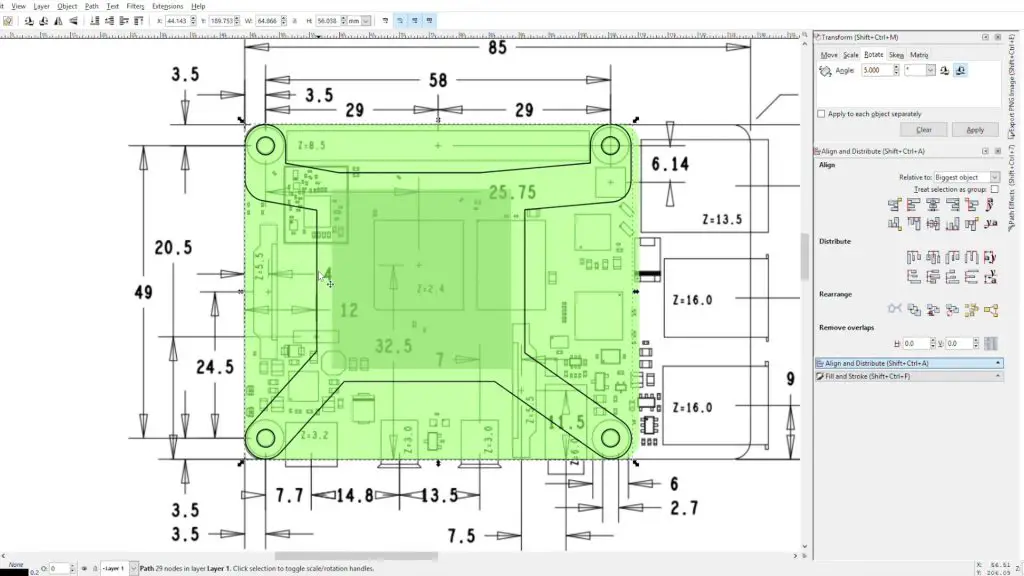

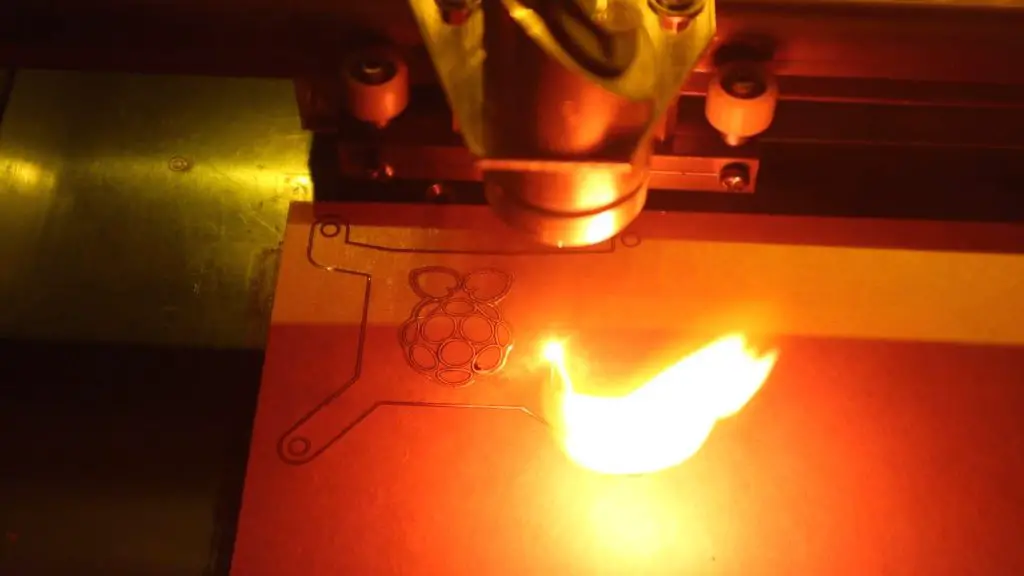

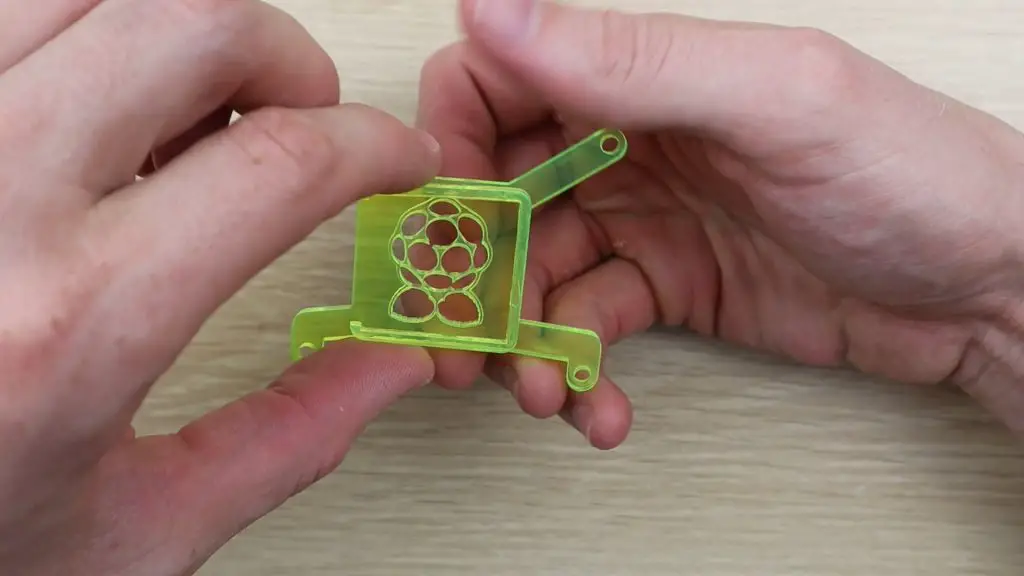

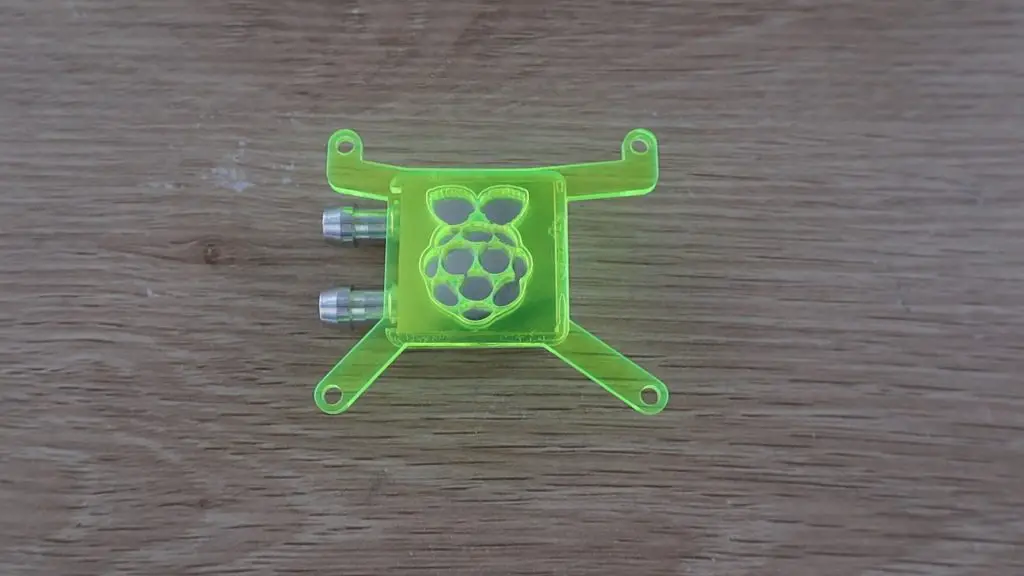

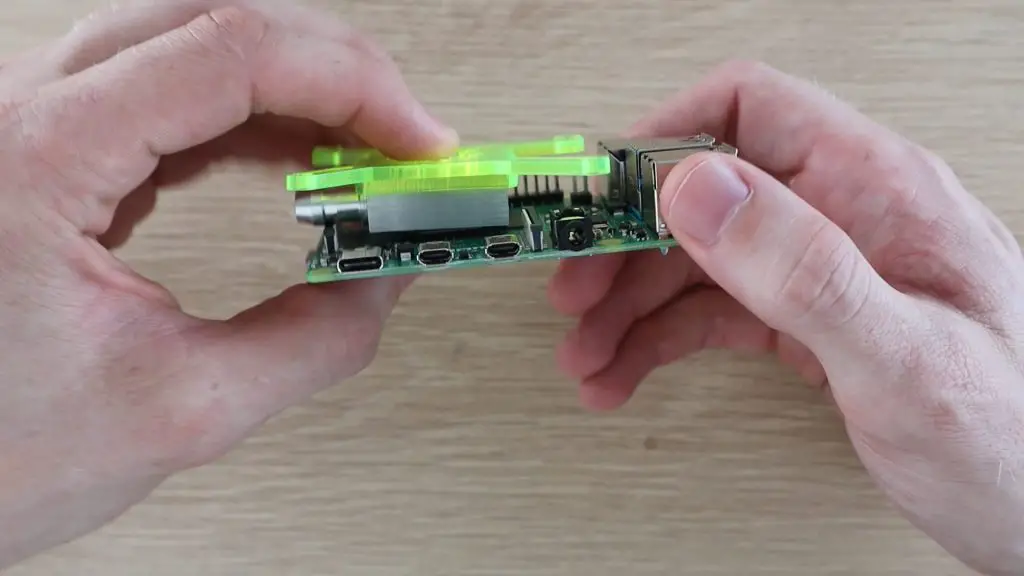

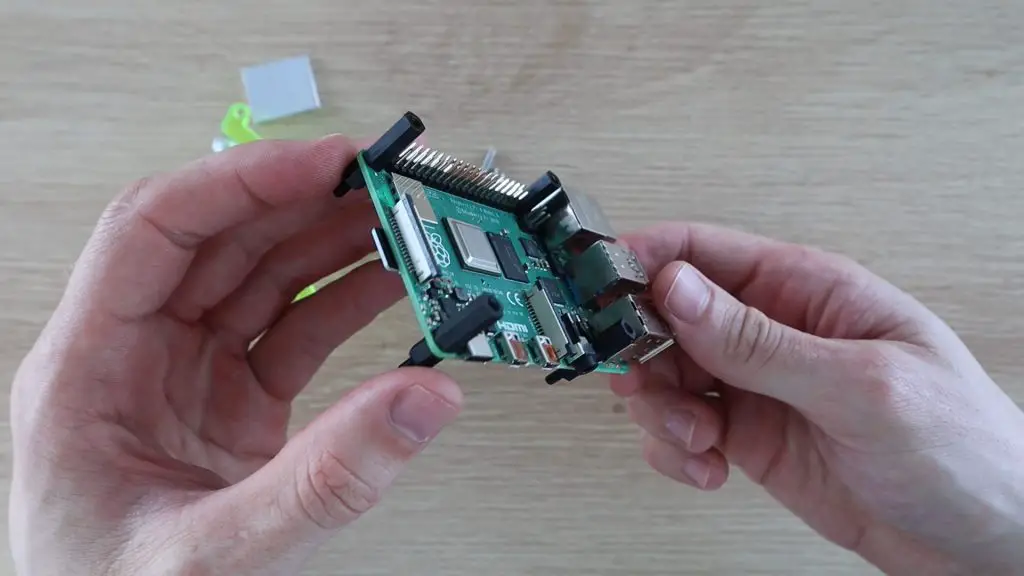

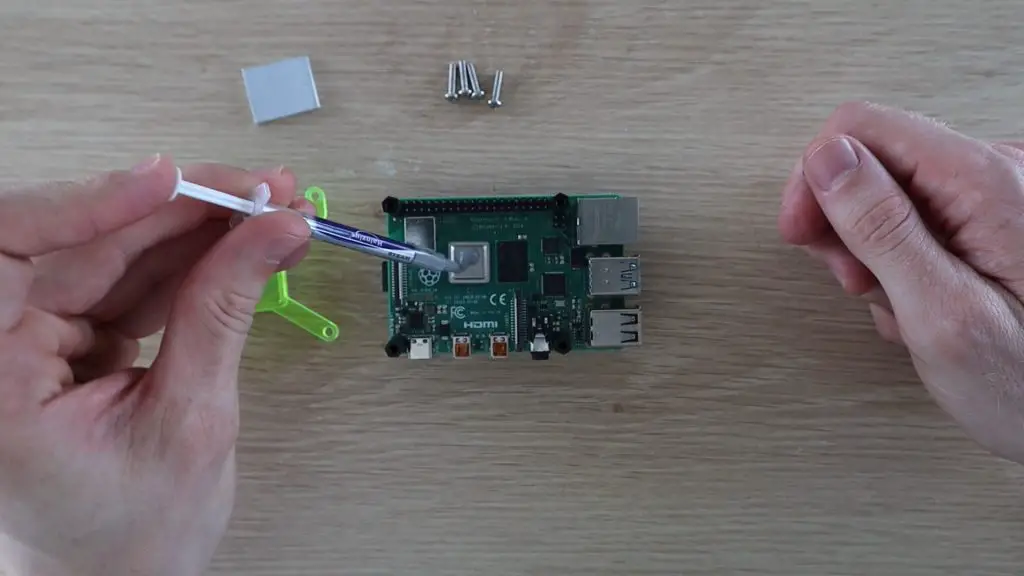

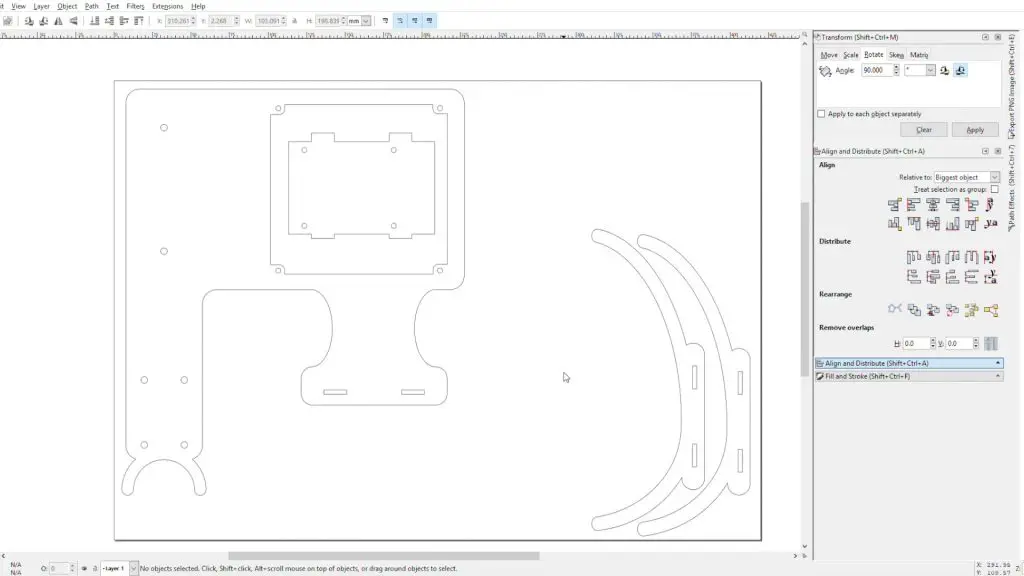

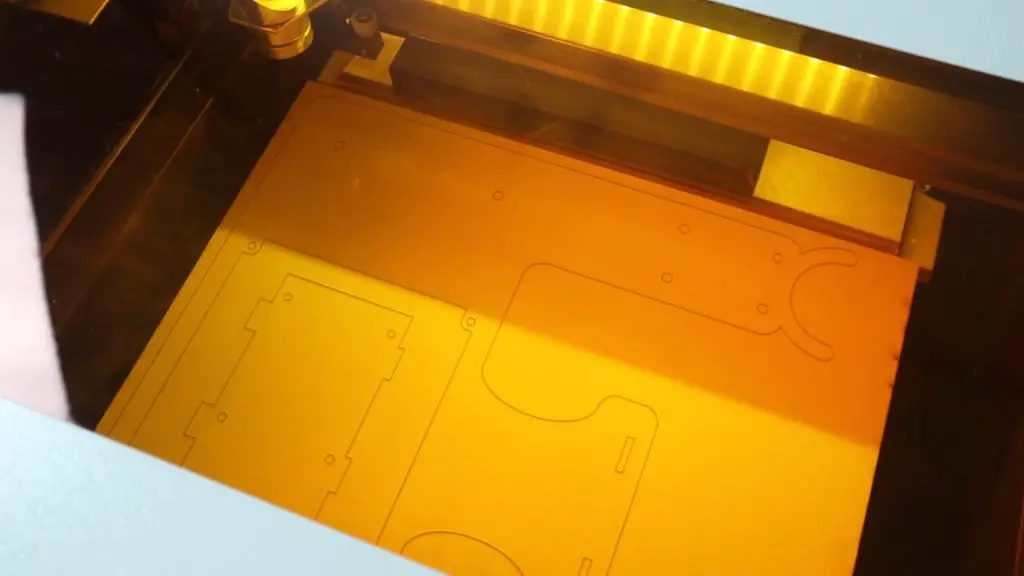

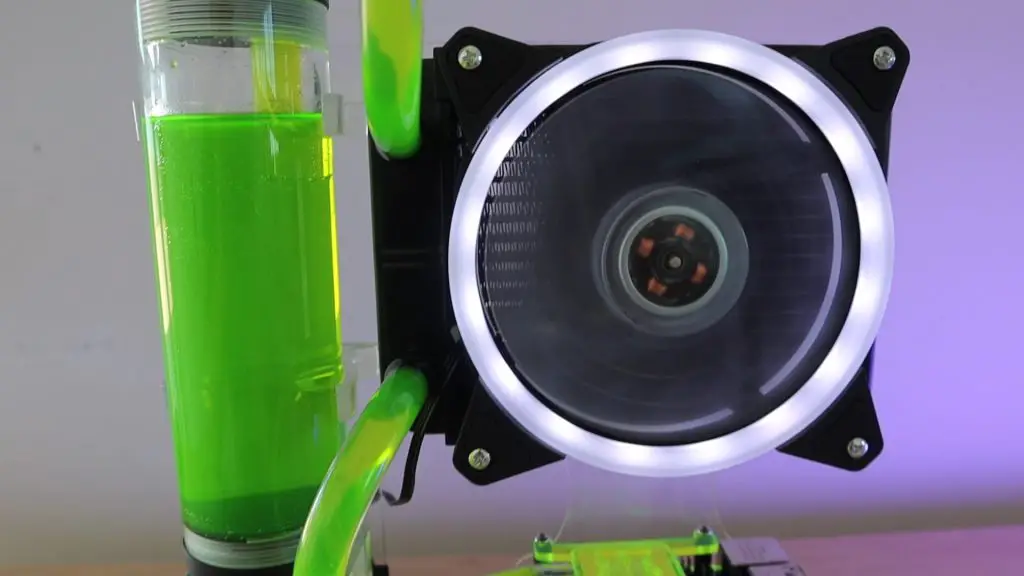

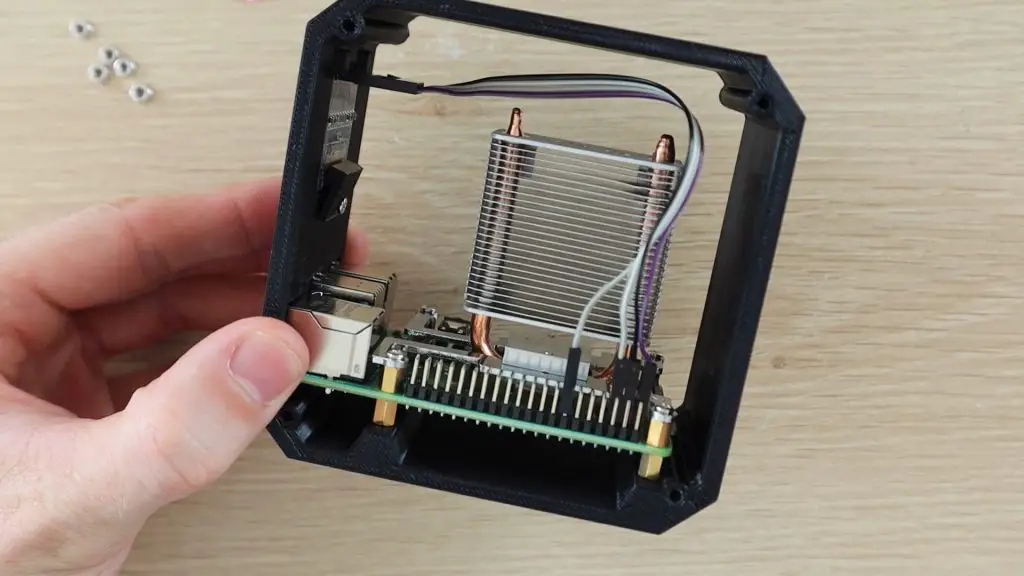

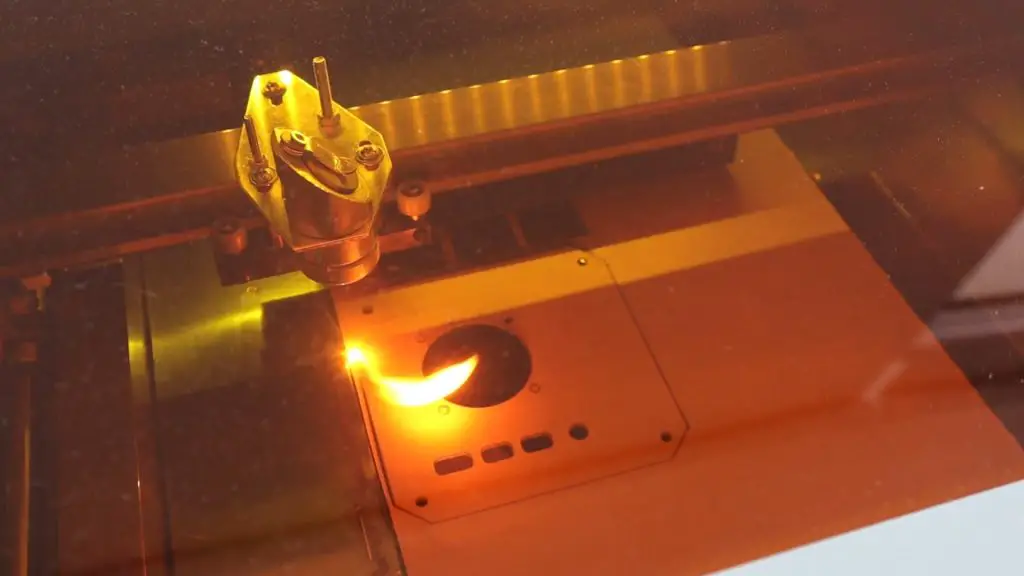

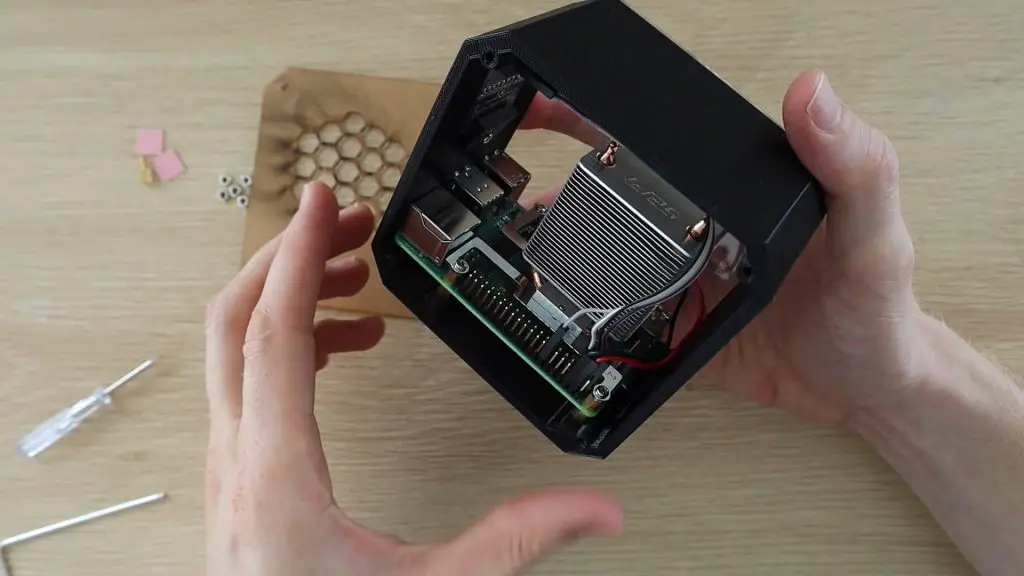

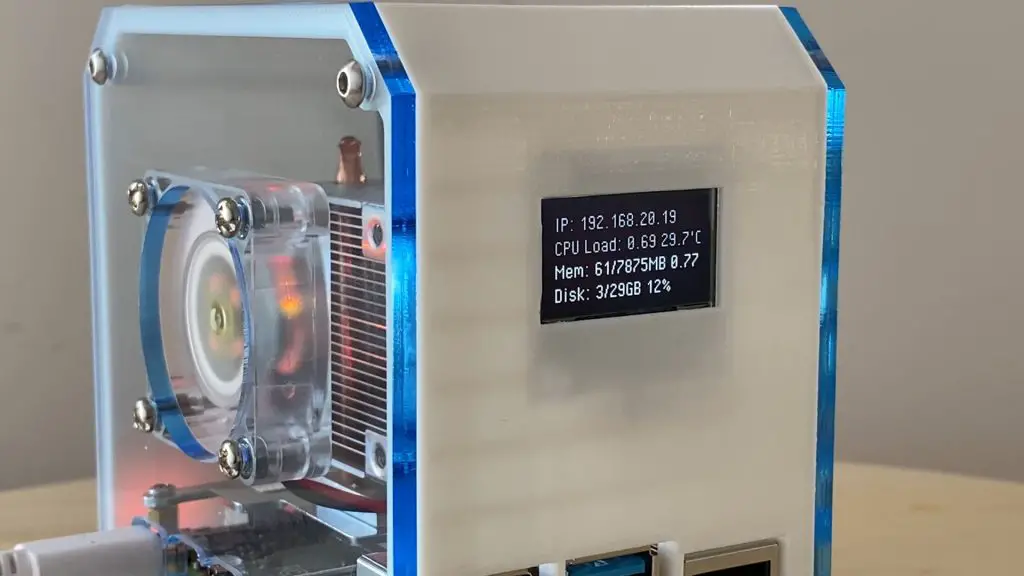

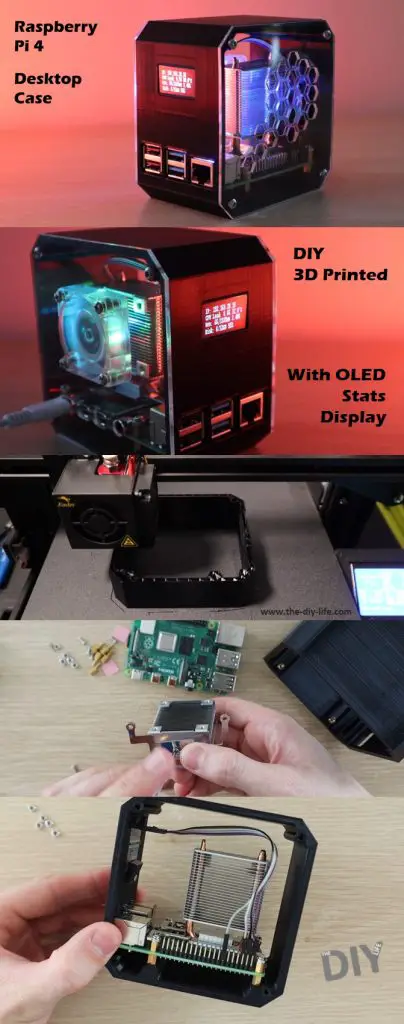

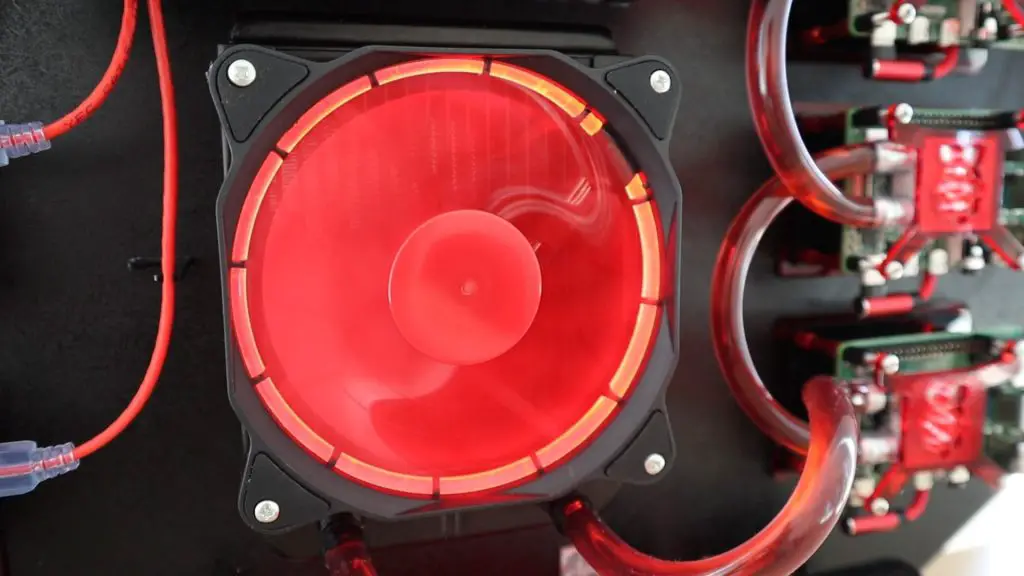

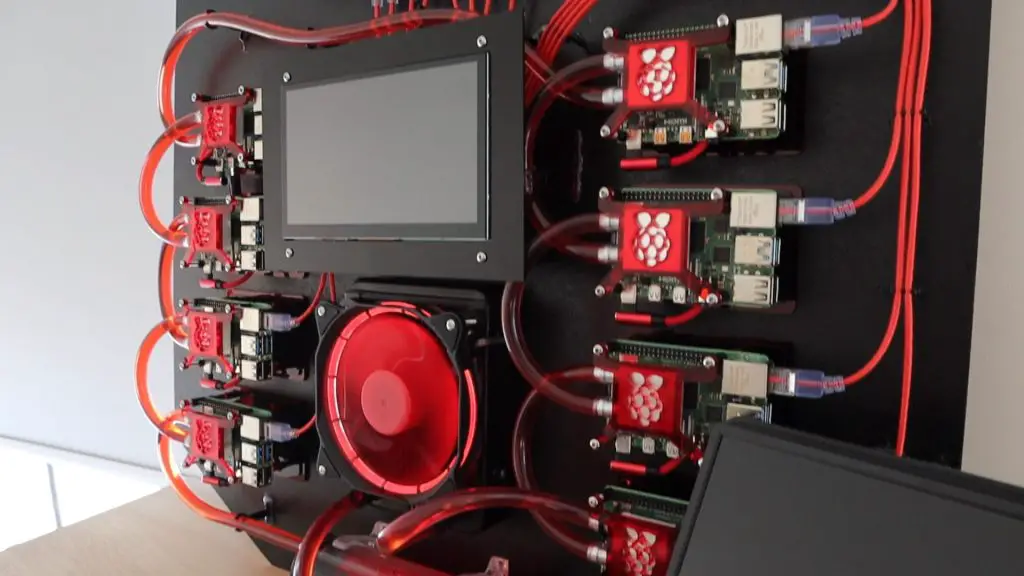

I recently built a water-cooled Raspberry Pi cluster and a lot of people asked how the cluster would compare to a computer because Raspberry Pi’s themselves aren’t seen as being particularly powerful.

If you haven’t already, have a look at my post on building the Pi Cluster.

How the cluster compares to a traditional computer isn’t really an easy question to answer. It depends on a number of factors and what metrics you measure it against. So this got me thinking of how to fairly compare the cluster to a computer in a way that doesn’t rely too heavily on the software being run and uses my Pi Cluster in the way it was intended when I built it,.

The cluster, and Raspberry Pi’s in general, aren’t designed for gaming or rendering high-end graphics, so obviously won’t perform well against a computer in this respect. But my intention behind building this cluster, apart from learning about and experimenting with cluster computing was to run mathematical models and simulations.

The Test Script

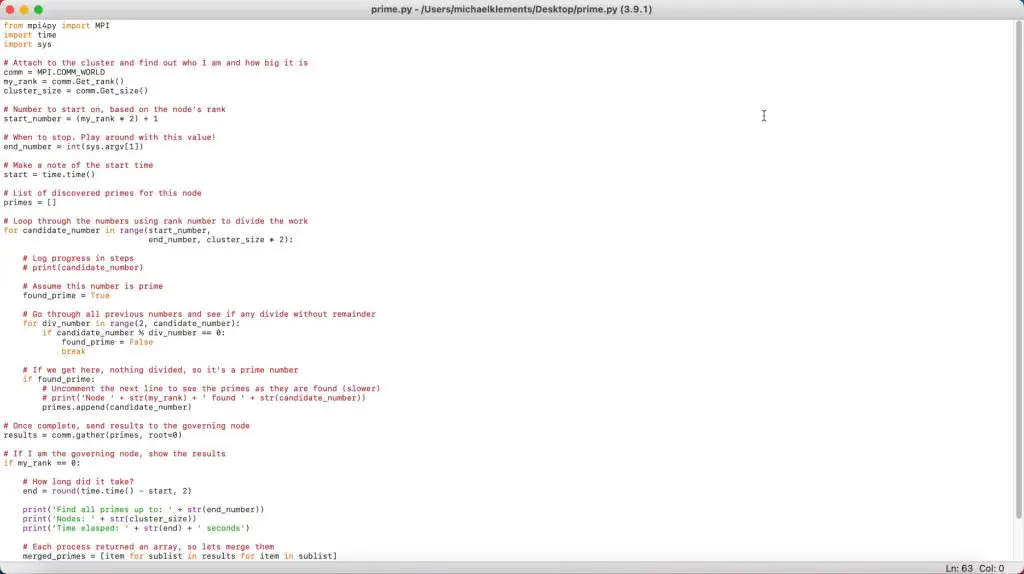

I initially thought of doing something along the lines of calculating Pi to a particular number of decimal places, but then I stumbled across a simple 4 node cluster setup mentioned in The Mag Pi which was used to find prime numbers up to a certain limit. This seemed like a good comparison as it is simple to understand and edit, it is easily adjustable and it can be run on Windows PCs, Macs and Raspberry Pi’s, so you can even join in and see how your computer compares.

The script just runs through each number, up to a limit, and checks its divisibility to figure out if it is a prime number or not. I have simplified their cluster script so that it can be run on a PC, Mac or single Raspberry Pi.

import time

import sys

#Start and end numbers

start_number = 1

end_number = 10000

#Record the test start time

start = time.time()

#Create variable to store the prime numbers and a counter

primes = []

noPrimes = 0

#Loop through each number, then through the factors to identify prime numbers

for candidate_number in range(start_number, end_number, 1):

found_prime = True

for div_number in range(2, candidate_number):

if candidate_number % div_number == 0:

found_prime = False

break

if found_prime:

primes.append(candidate_number)

noPrimes += 1

#Once all numbers have been searched, stop the timer

end = round(time.time() - start, 2)

#Display the results, uncomment the last to list the prime numbers found

print('Find all primes up to: ' + str(end_number))

print('Time elasped: ' + str(end) + ' seconds')

print('Number of primes found ' + str(noPrimes))

#print(primes)I know that this is a very inefficient way of searching for prime numbers, but the intention is to make the script computationally expensive so that the processors have to work. There are some interesting thoughts and algorithms for finding prime numbers if you’d like to do some further reading.

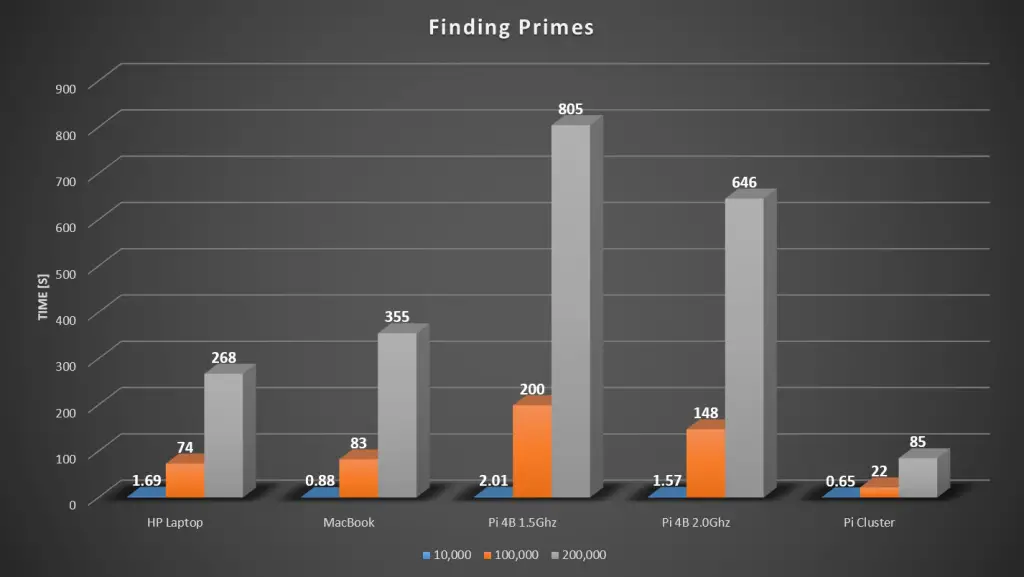

For each setup, we’ll be testing the time it takes to find all prime numbers up to 10,000, 100,000 and 200,000.

I’ll be doing 5 comparisons, running the simulation on two laptops – a 2020 MacBook Air and a somewhat outdated HP Laptop running Windows 10 Pro. We’ll then compare these laptops to a single Pi 4B running at 1.5Ghz, then overclock the single Pi to 2.0Ghz, and then finally run the simulation on the Raspberry Pi Cluster with all of the Pis overclocked to 2.0Ghz.

There were a few requests on my build video to compare the cluster to a one of AMDs Ryzen CPU’s. So if any of you are running one, please try running the Python script which you can download above and share the results in the comments section. I’d also be interested to see how the Pi 400 performs if anyone has one of those.

Edit – Multi-process Test Script

Thanks to Adi Sieker for putting together a multi-process version of the script. This script makes use of all available cores and threads on the computer it’s being run on, so should give much better comparative results for multi-core processors.

I’ll add my updated test results for each system running this script at the end of this post.

import multiprocessing as mp

import time

#max number to look up to

max_number = 10000

#four processes per cpu

num_processes = mp.cpu_count() * 4

def chunks(seq, chunks):

size = len(seq)

start = 0

for i in range(1, chunks + 1):

stop = i * size // chunks

yield seq[start:stop]

start = stop

def calc_primes(numbers):

num_primes = 0

primes = []

#Loop through each number, then through the factors to identify prime numbers

for candidate_number in numbers:

found_prime = True

for div_number in range(2, candidate_number):

if candidate_number % div_number == 0:

found_prime = False

break

if found_prime:

primes.append(candidate_number)

num_primes += 1

return num_primes

def main():

#Record the test start time

start = time.time()

pool = mp.Pool(num_processes)

#0 and 1 are not primes

parts = chunks(range(2, max_number, 1), 1)

#run the calculation

results = pool.map(calc_primes, parts)

total_primes = sum(results)

pool.close()

#Once all numbers have been searched, stop the timer

end = round(time.time() - start, 2)

#Display the results, uncomment the last to list the prime numbers found

print('Find all primes up to: ' + str(max_number) + ' using ' + str(num_processes) + ' processes.')

print('Time elasped: ' + str(end) + ' seconds')

print('Number of primes found ' + str(total_primes))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()Testing The Laptops And Individual Pi

Now that we know what we’re going to be doing, let’s get started with testing the computers.

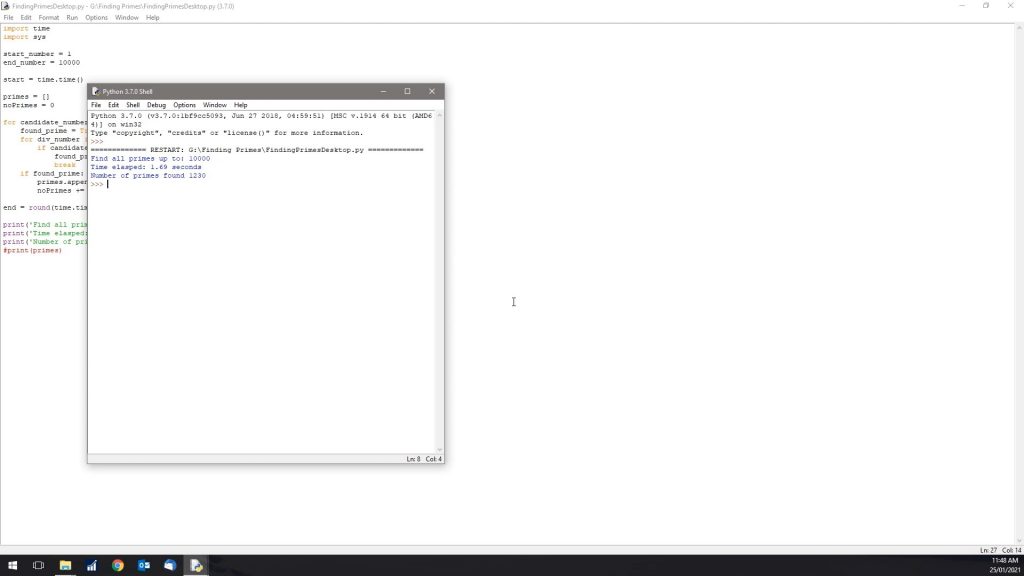

I’ll start off on my Windows PC. The windows PC has a 7th generation dual-core i5 processor running at 2.5GHz.

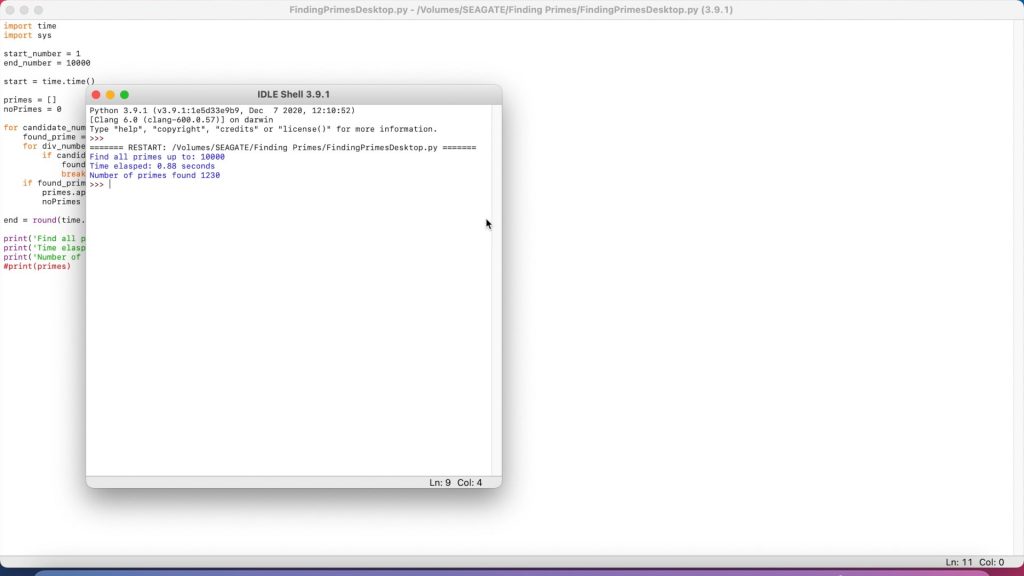

Let’s start off by running the script to 10,000.

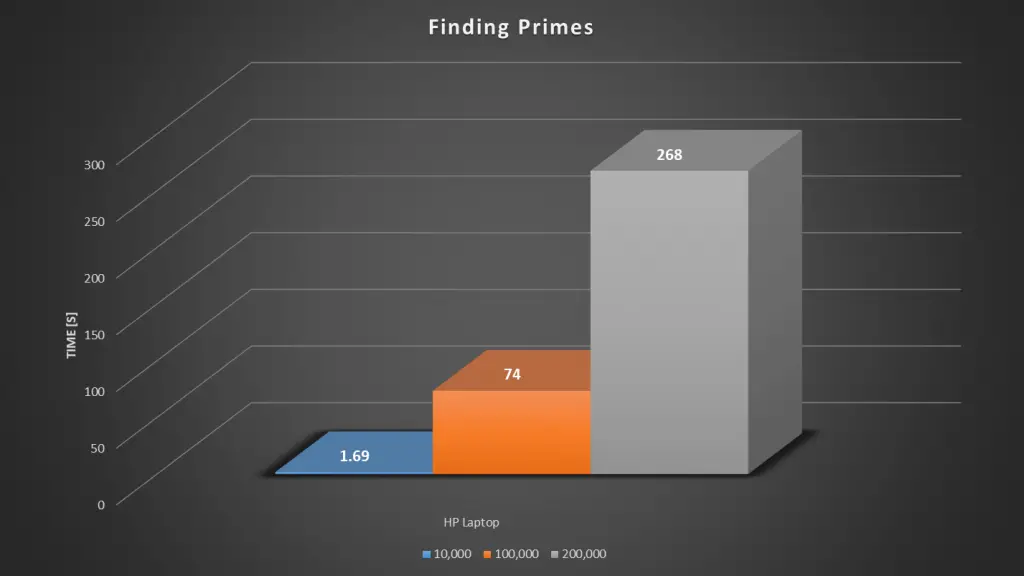

So as expected, that was completed pretty quickly, 1.69 seconds to find 1230 prime numbers below 10,000.

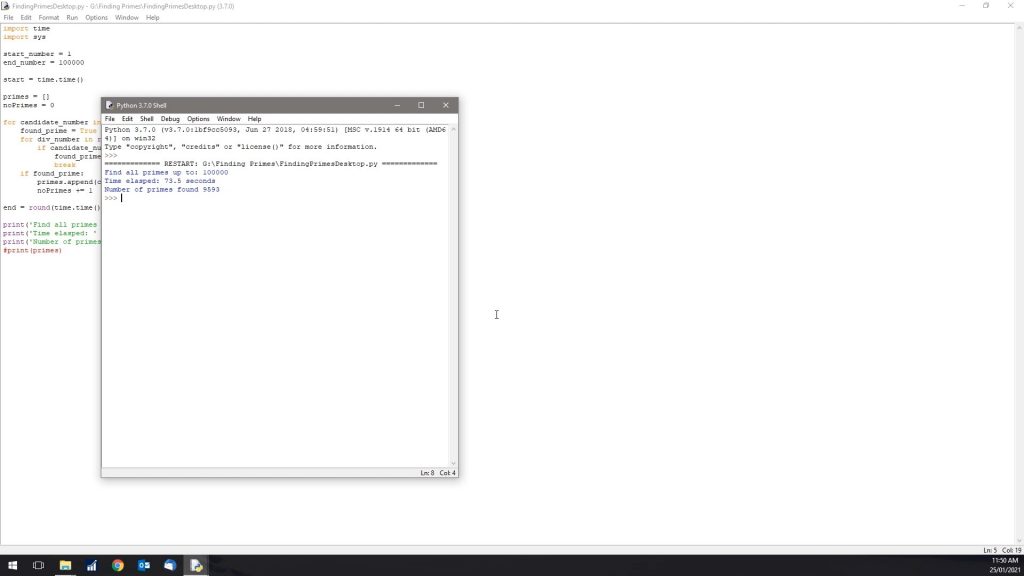

Now let’s try 100,000. Remember that even though 100,000 is only ten times more than 10,000, it’s going to take significantly longer than 10 times the time, because there are exponentially more factors to check as the numbers get larger.

So running the test to 100,000, we get a time of 73 seconds, which is a minute and 13 seconds and we found 9593 prime numbers.

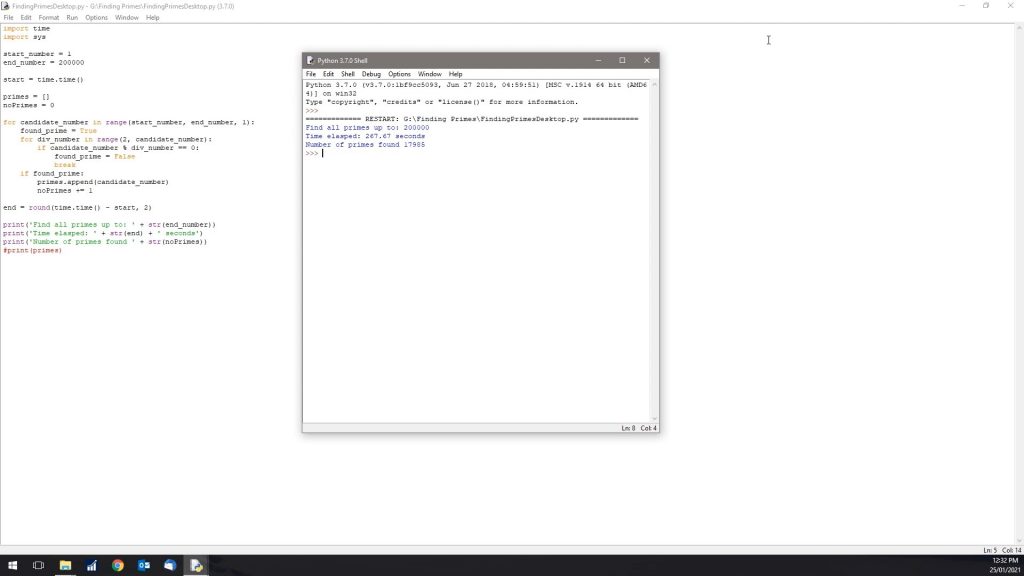

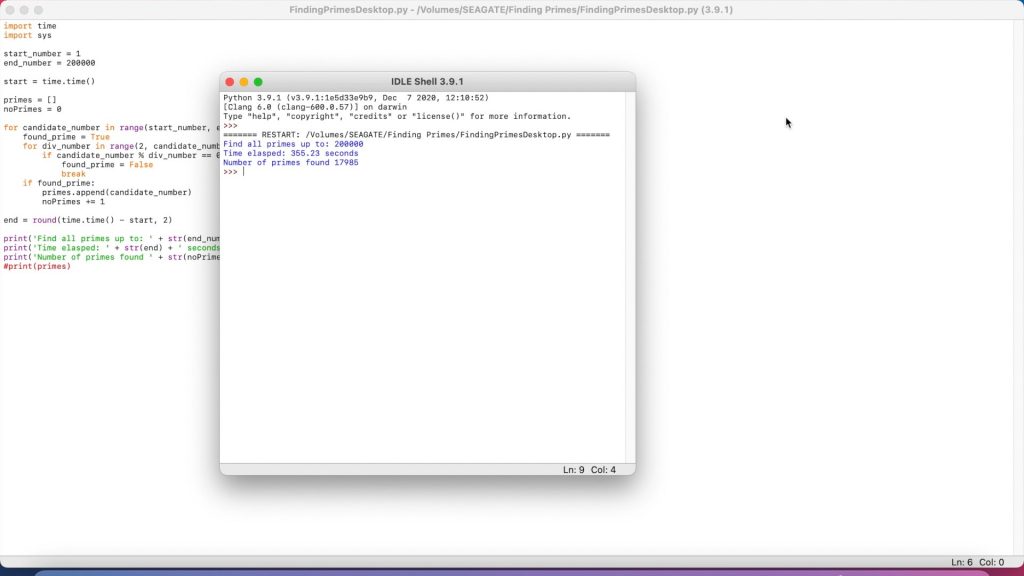

Lastly, lets try 200,000.

So it took 267 seconds or a little under 5 minutes to find the prime numbers to 200,00 and we found 17,985 primes.

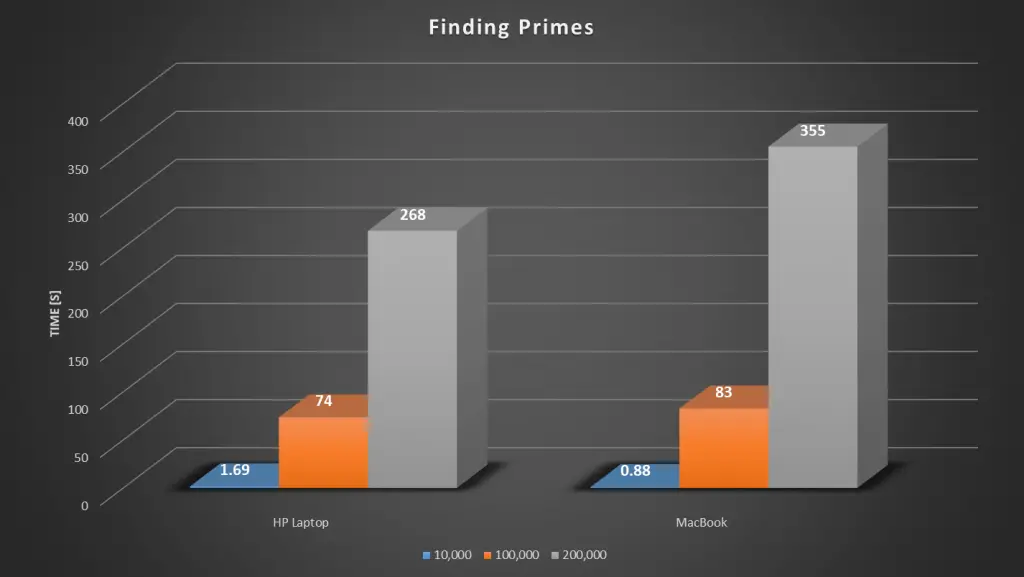

Here’s a summary of the HP laptop’s results.

Next, we’ll look at the MacBook Air. The MacBook Air has a 1.6 GHz Dual Core i5 processor, let see how that compares to the older HP laptop. We’d expect the MacBook to be a bit slower than the PC as it’s CPU is only running at 1.6GHz, while the PC is running at 2.5Ghz.

The MacBook Air was quicker to 10,000 but then took a little longer than the PC for the next two tests, taking just under 6 minutes to find the primes up to 200,000.

Here’s a summary of the results of the two tests so far:

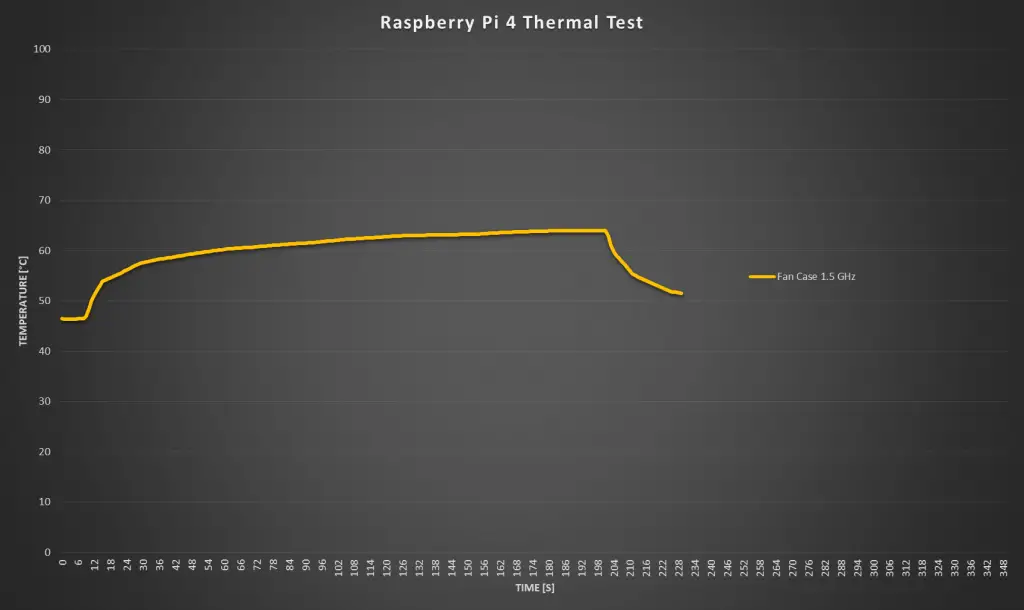

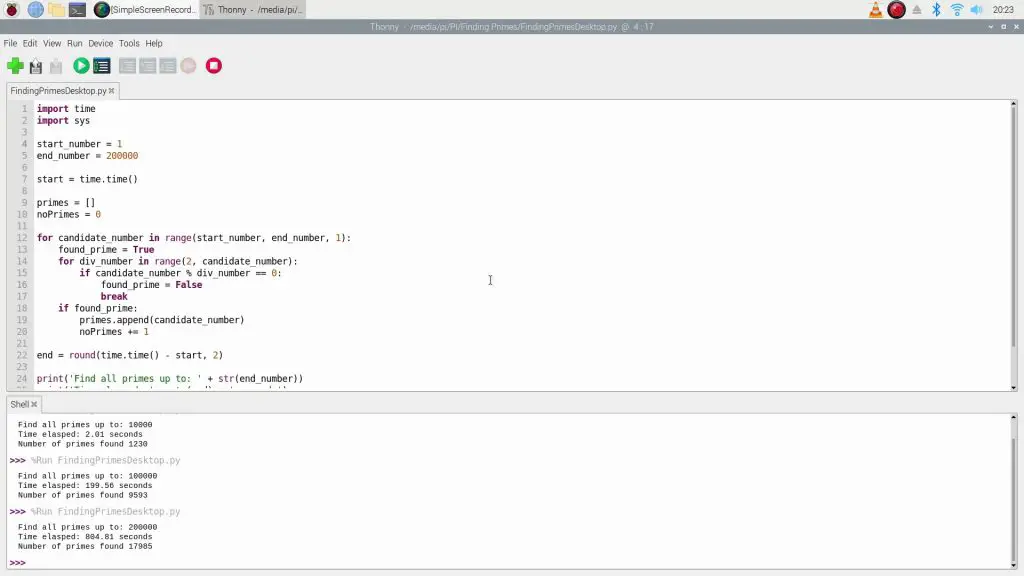

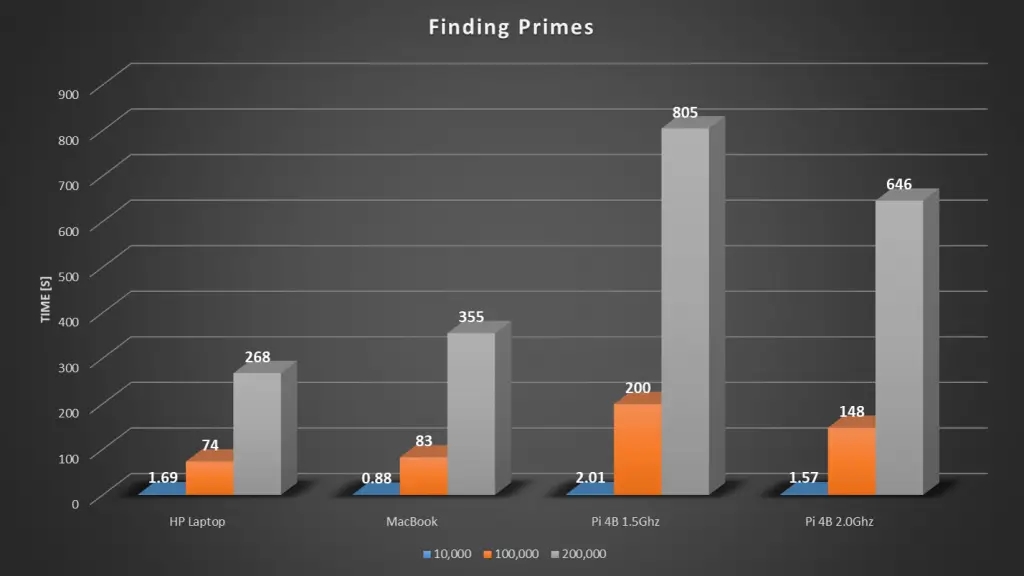

Let’s now move on to the singe Raspberry Pi running at 1.5Ghz.

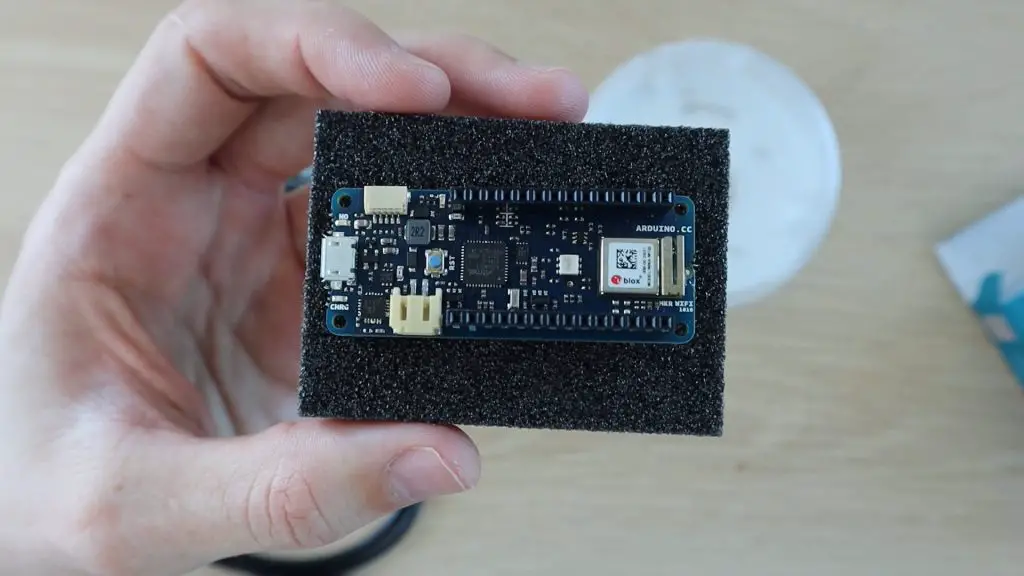

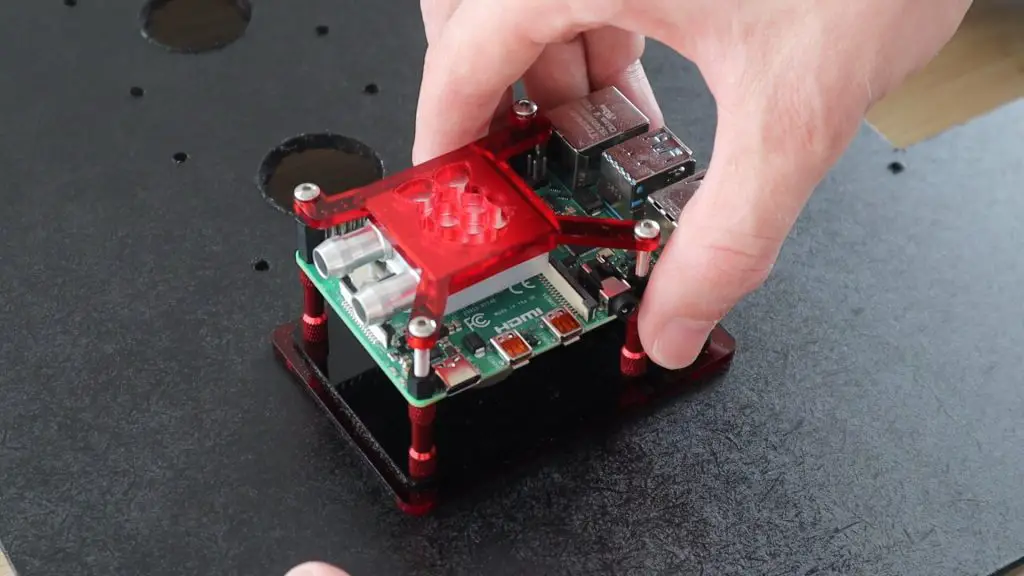

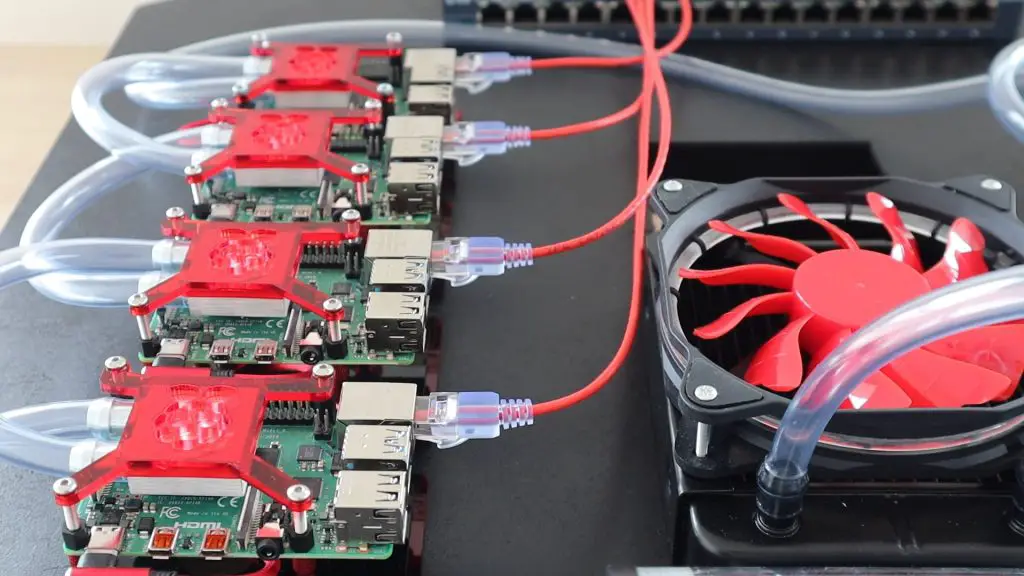

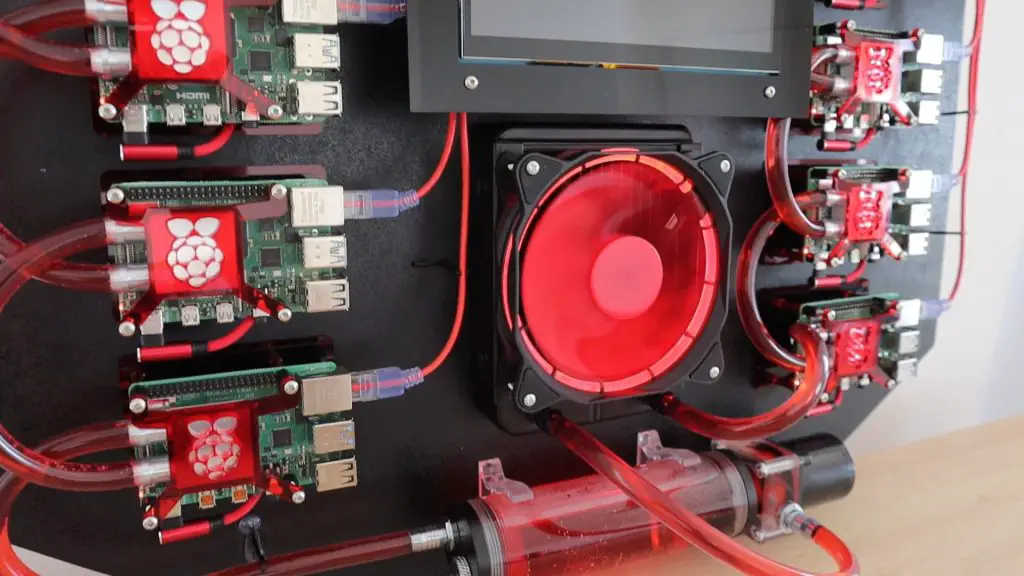

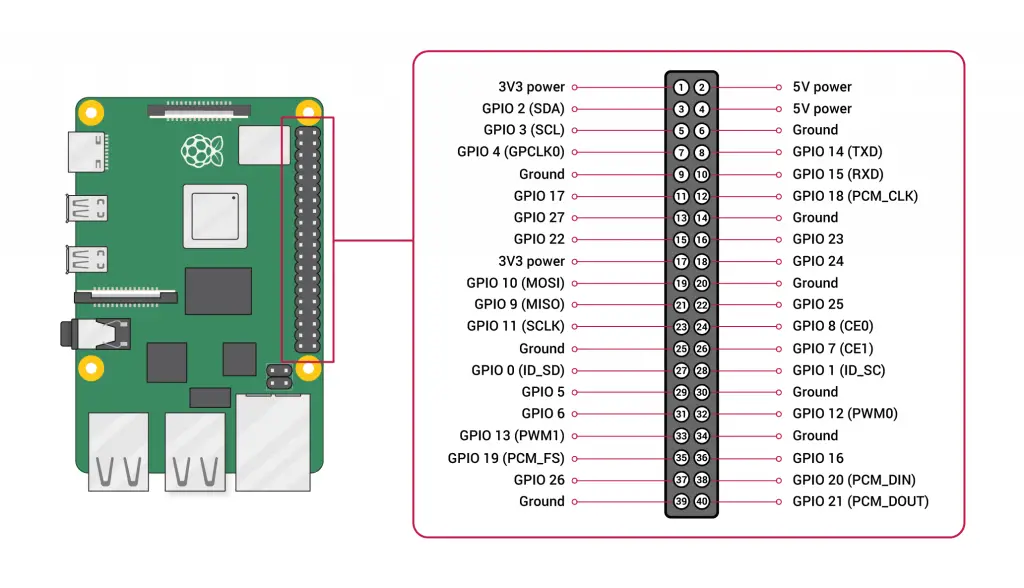

The Pi 4B has a quad-core ARM Coretex-A72 processor.

Even to 10,000, we can already see that the Pi is quite a bit slower than the other computers, taking 2 seconds for the first 10,000 and taking a little over 13 minutes to get to 200,000.

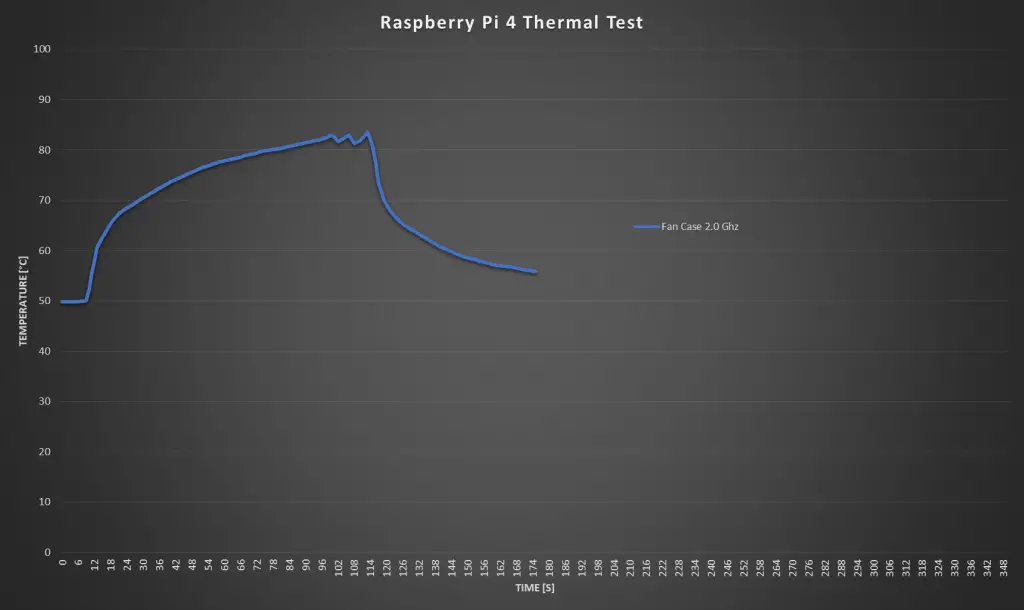

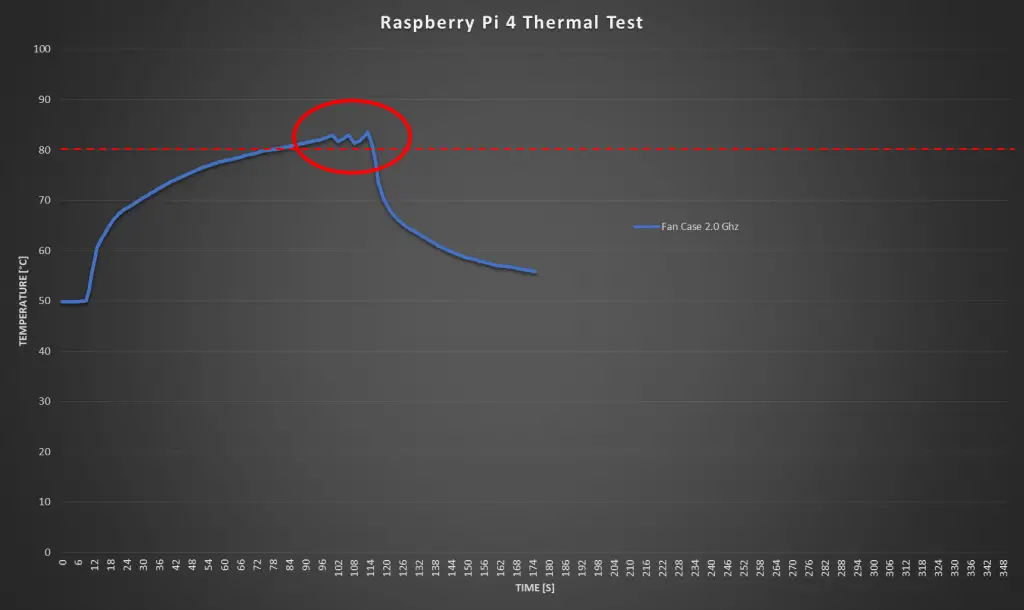

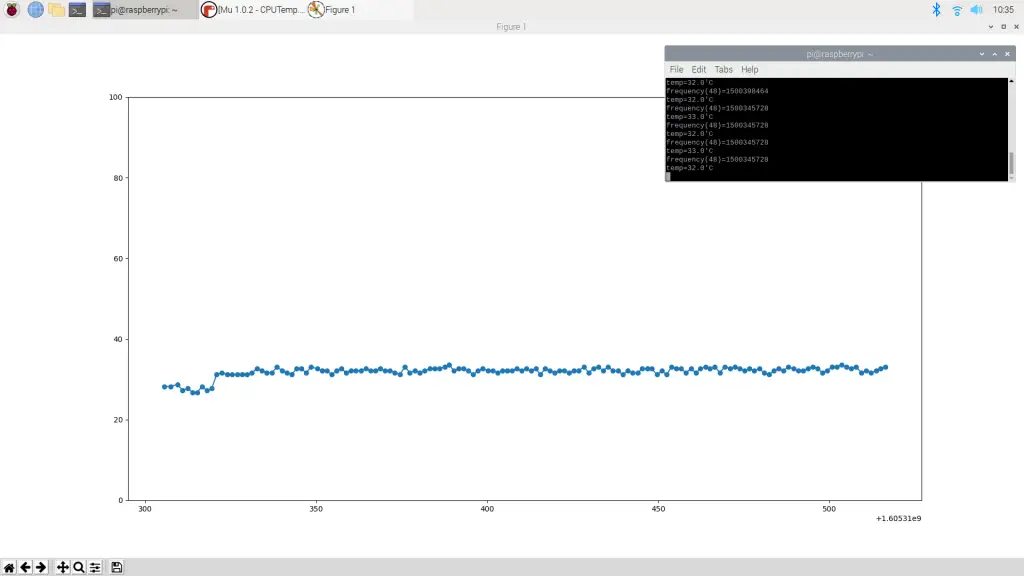

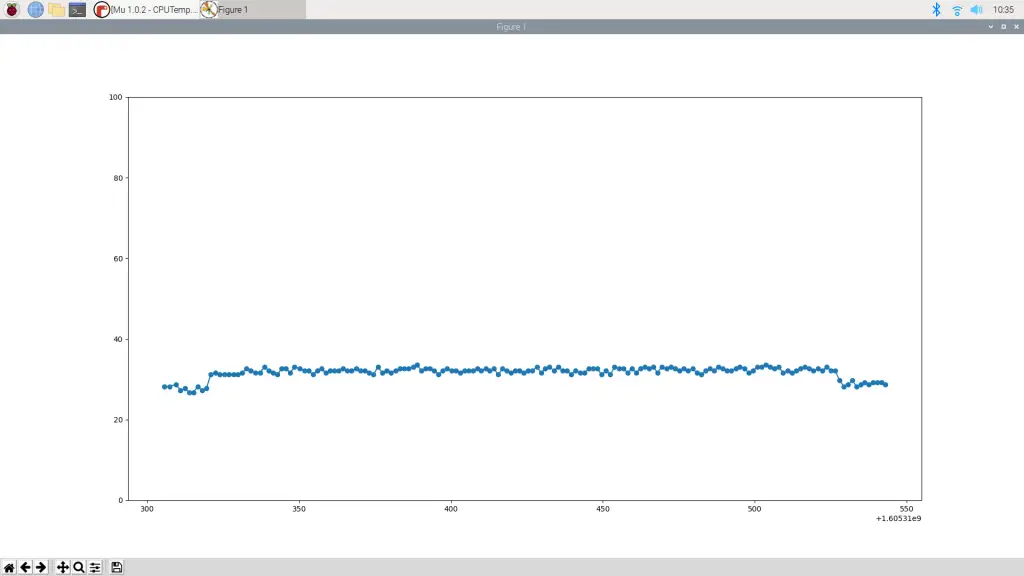

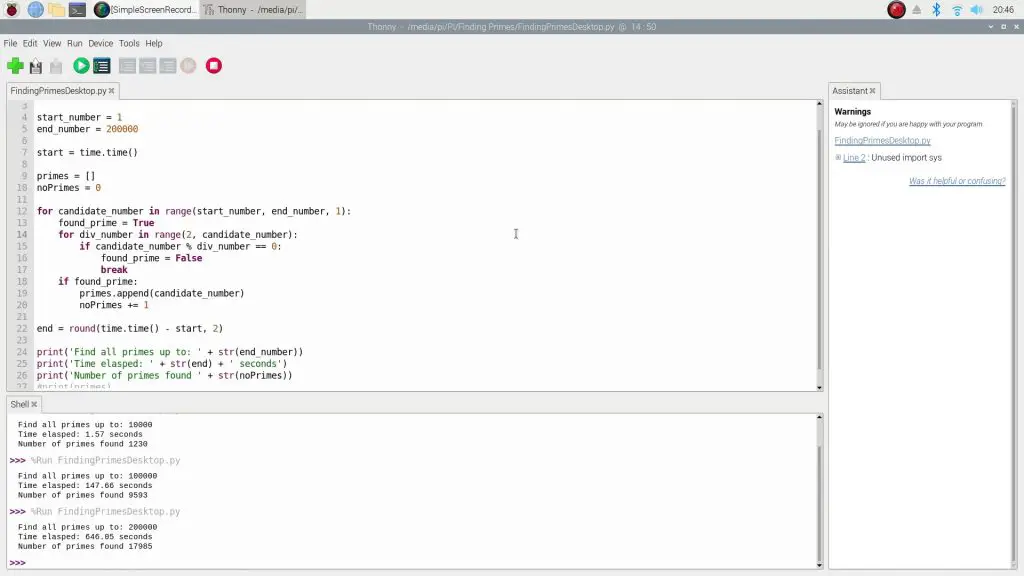

Next we’ll overclock the Pi to 2.0Ghz and see what sort of difference we see.

Overclocking the Pi has made a bit of an improvement. It took 1.57 seconds to 10,000, and around 11 minutes to get to 200,000.

Here’s a summary of the results of our tests of the individual computers:

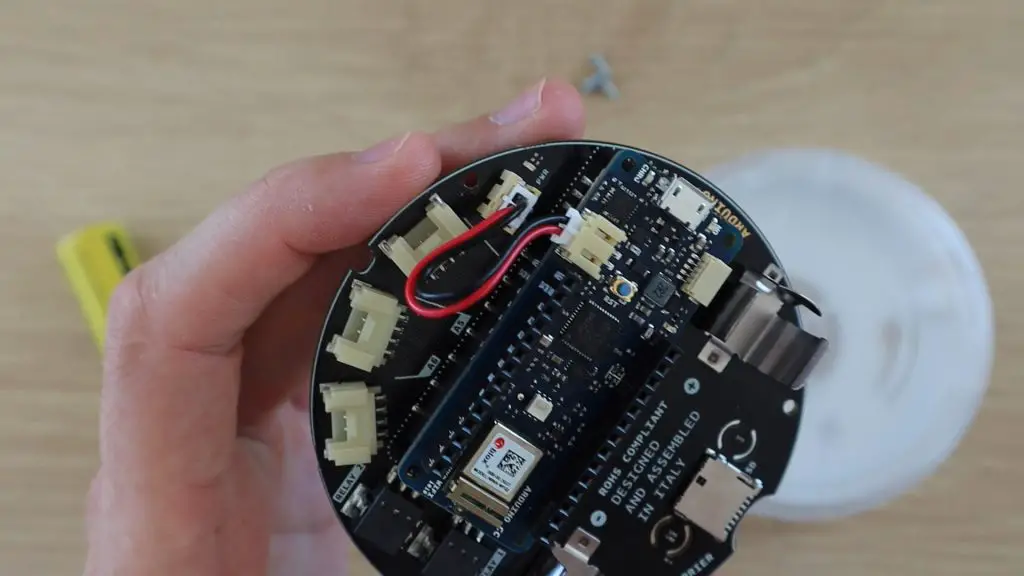

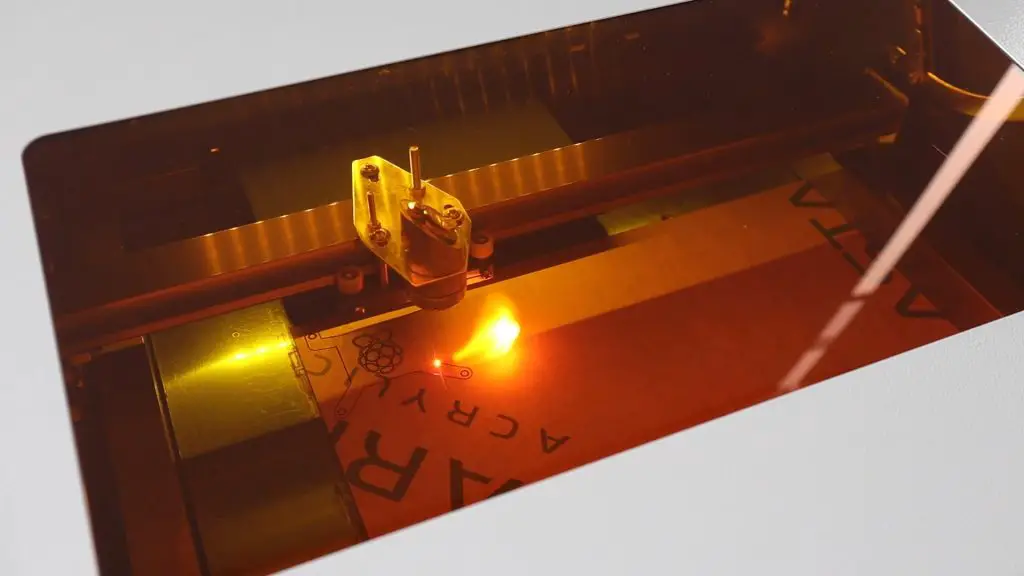

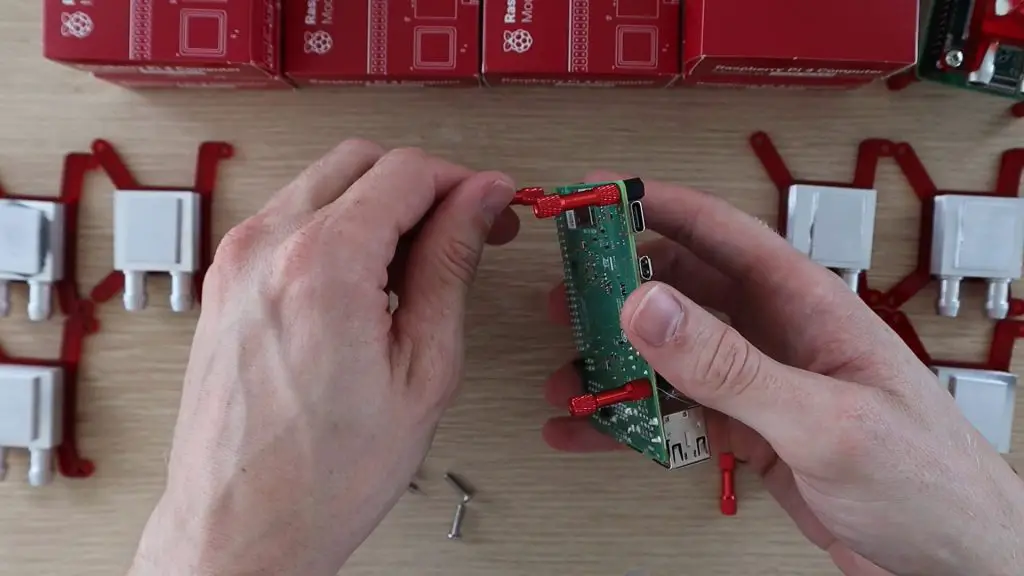

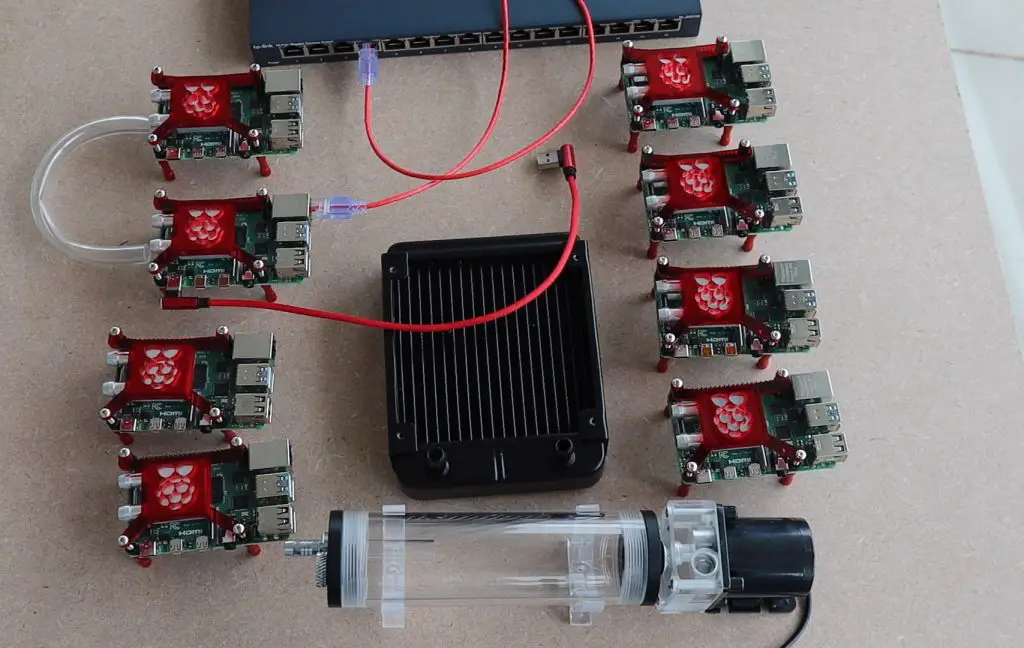

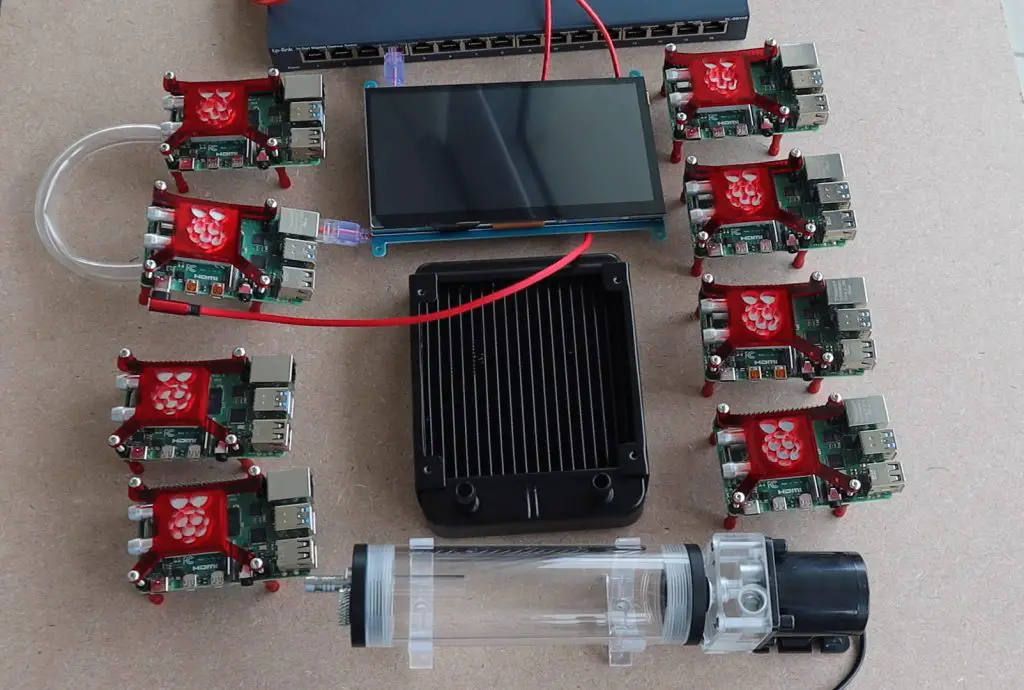

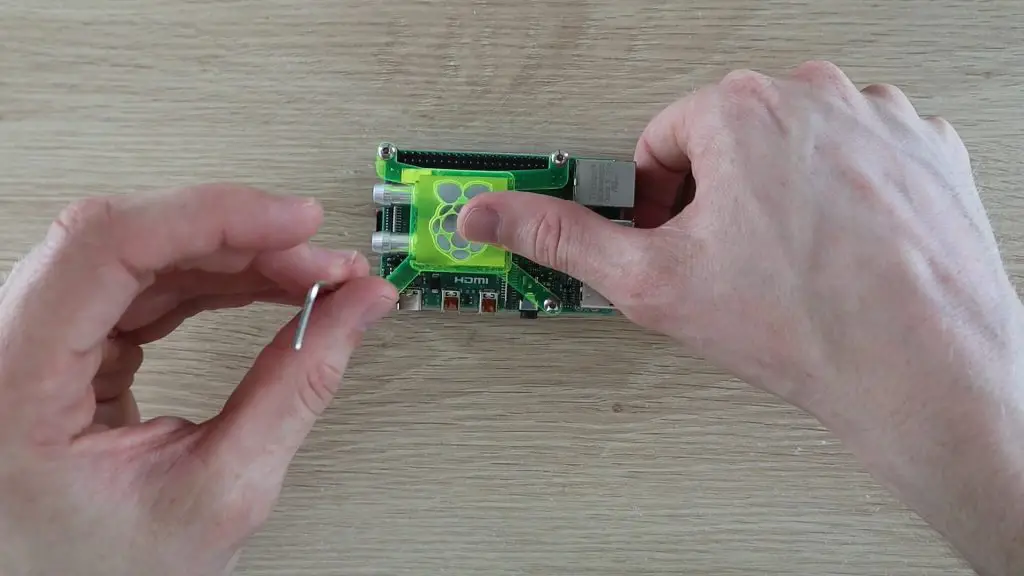

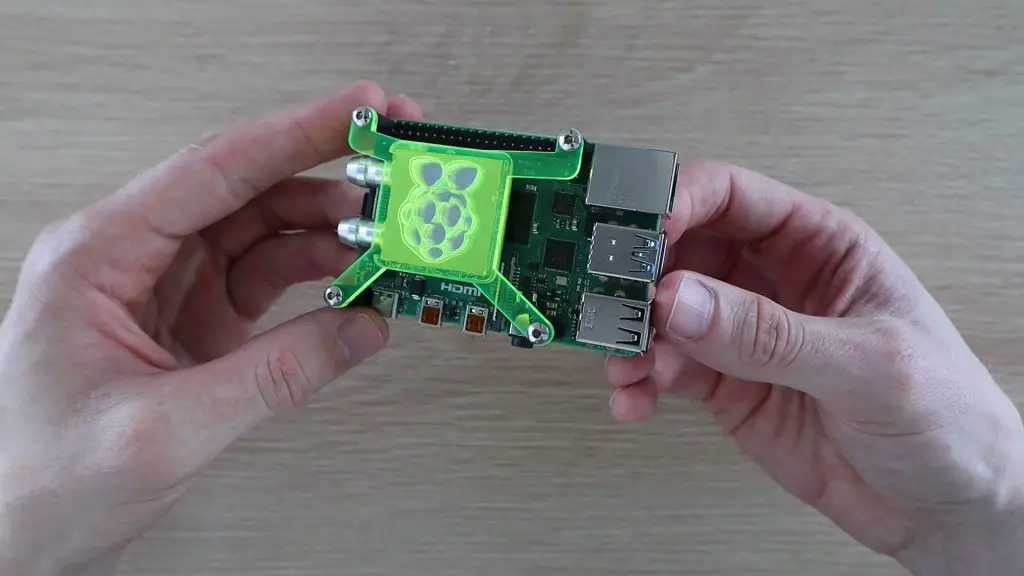

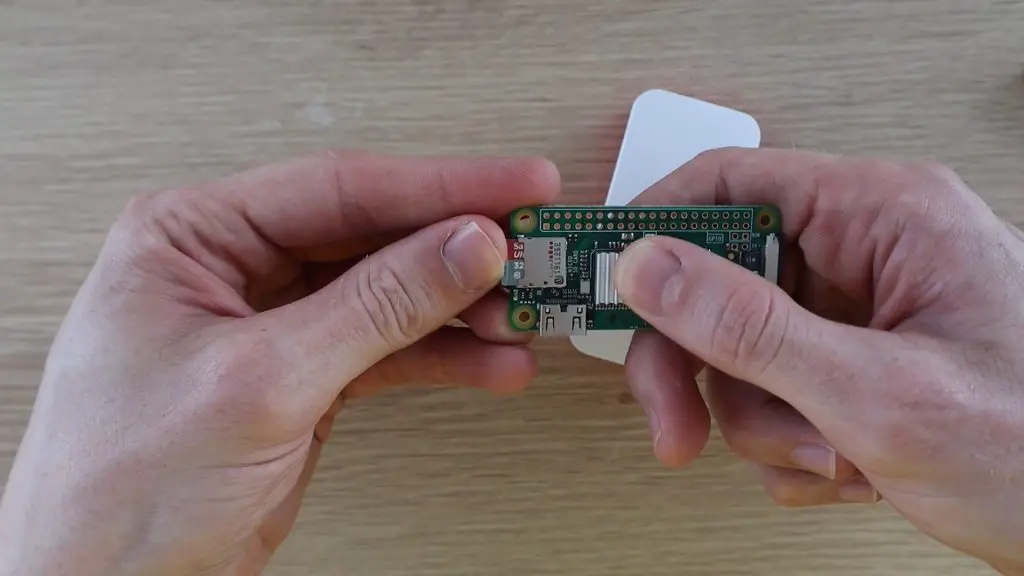

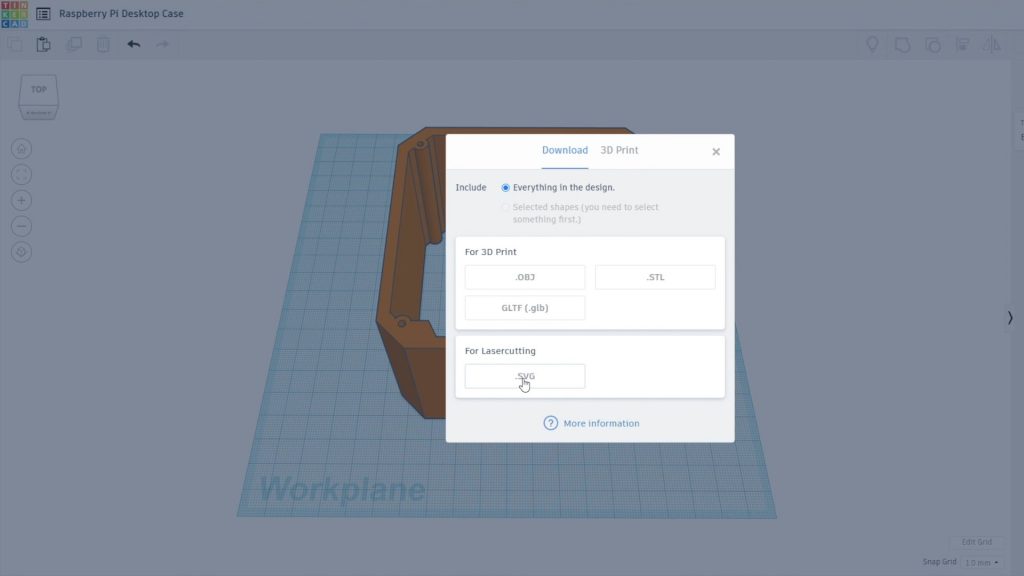

Setting Up The Raspberry Pi Cluster

Next, we need to get the Pi’s all overclocked and working together in a cluster. To do this, there are a couple of things we need to set up.

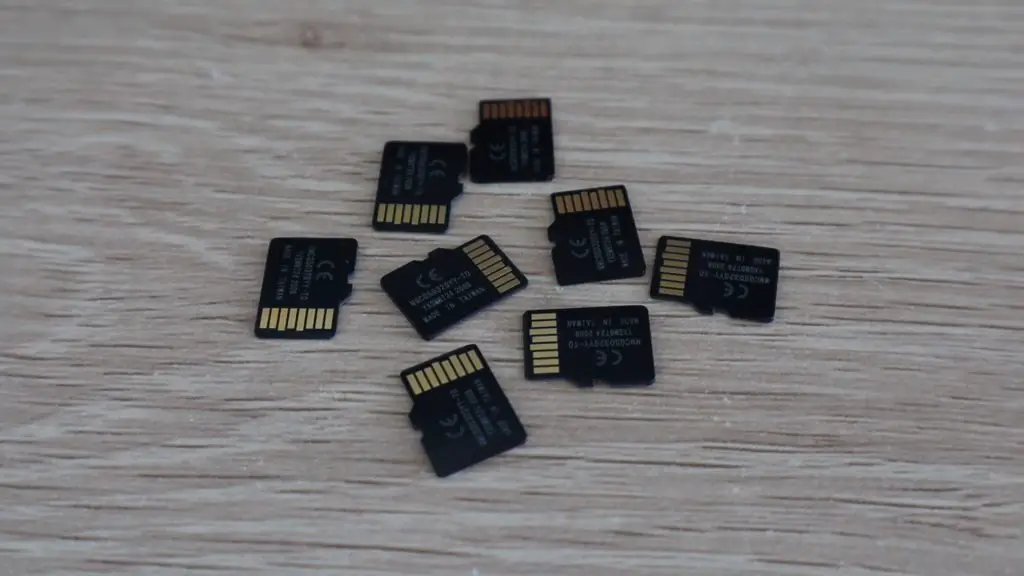

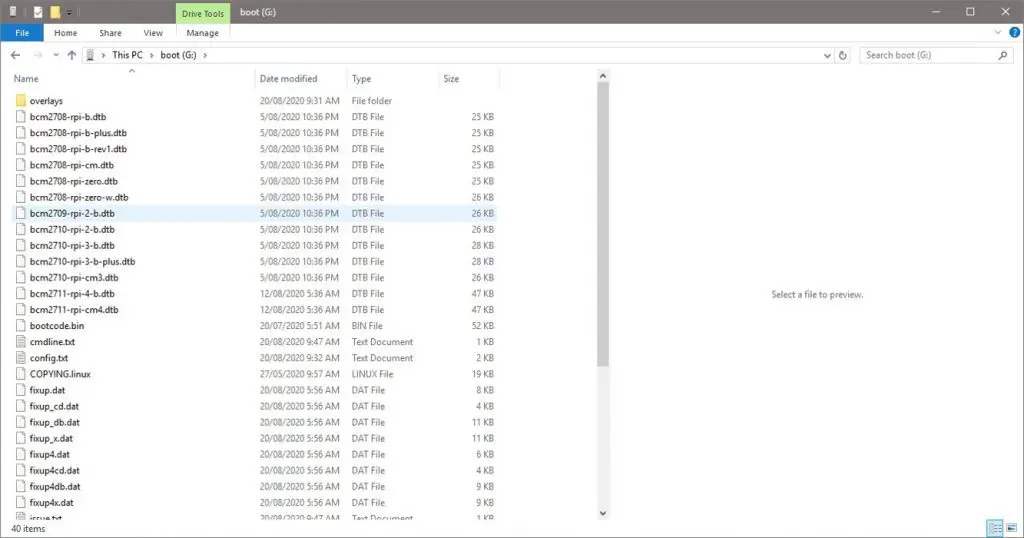

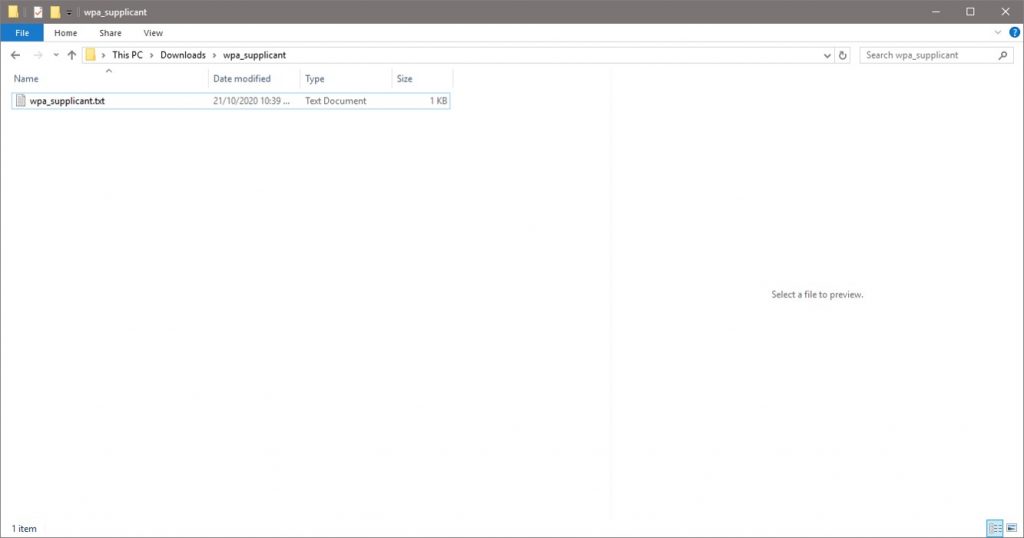

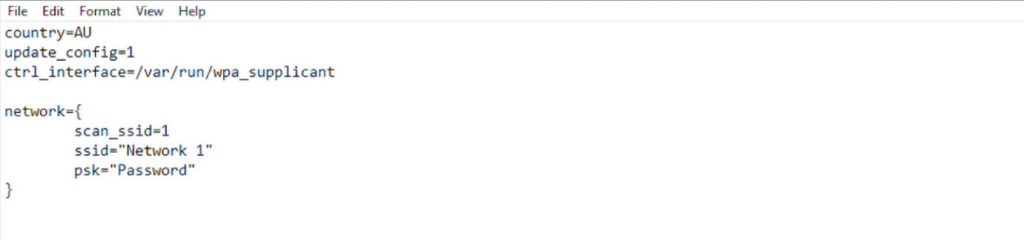

I’ve installed a fresh copy of Raspberry Pi OS on the host or master node and then a copy of Raspberry Pi OS Lite on the other 7 nodes.

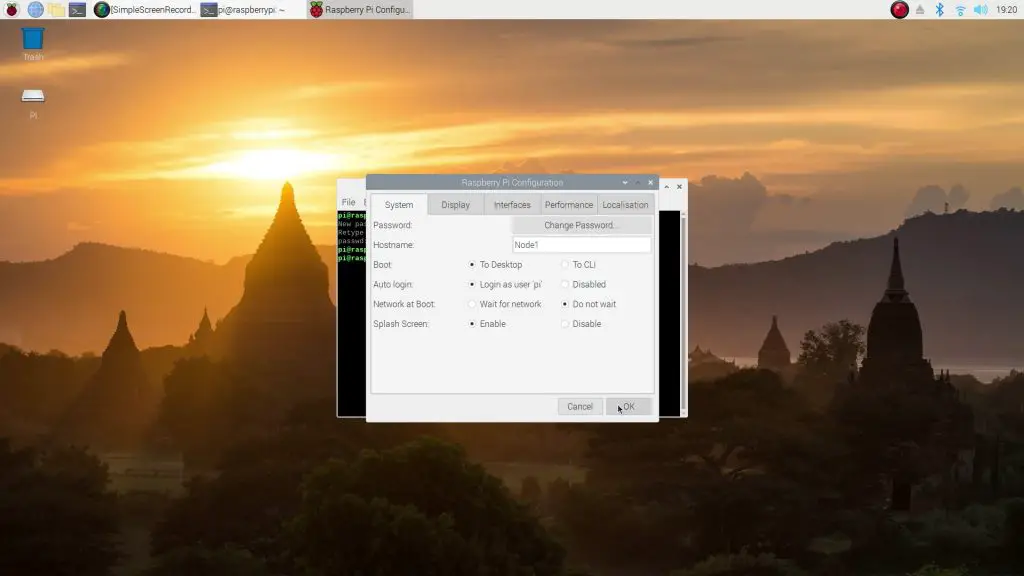

Prepare Each Node For SSH

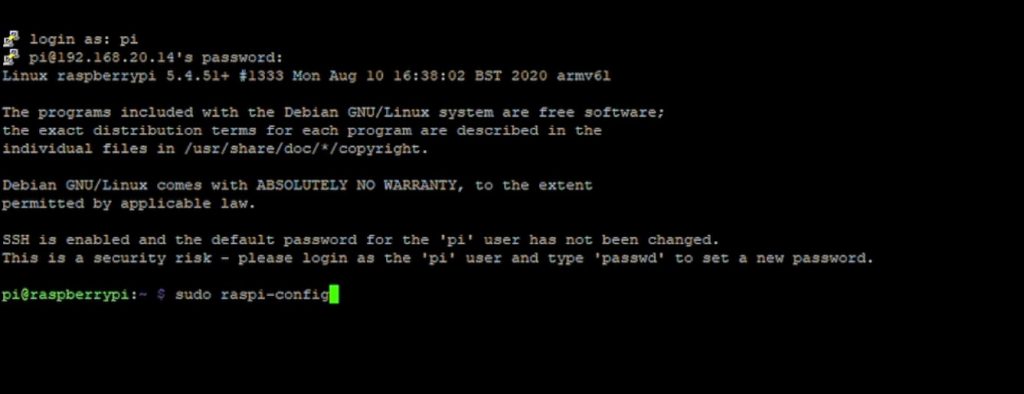

Boot them up and then run the following lines to update them:

sudo apt -y update

sudo apt -y upgradeNext, run;

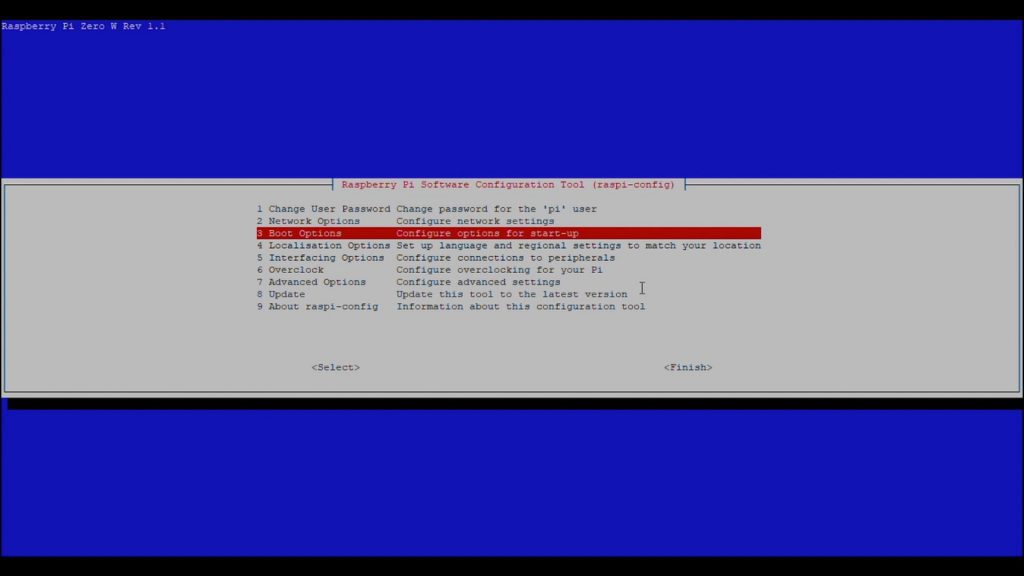

sudo raspi-configAnd change each Pi’s password, hostname. I used hostnames Node1, Node2 etc.. Also, make sure that SSH is turned on for each Pi so that you can access them over the network.

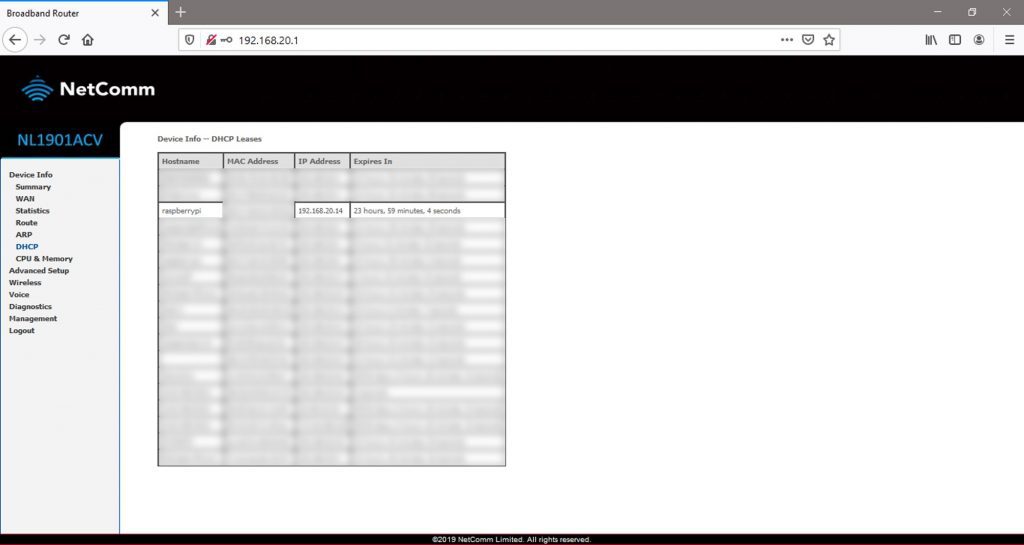

Next, you need to assign static IP addresses to your Pi’s. Make sure that you’re working in a range which is not already assigned by your router if you’re not working on a dedicated network.

sudo nano /etc/dhcpcd.confThen add the following lines to the end of the file:

interface eth0

static ip_address=192.168.0.1/24I used IP addresses 192.168.0.1, 192.168.0.2, 192.168.0.3 etc.

Then reboot your Pi’s and you should then be able to do the rest of the setup through Node 1.

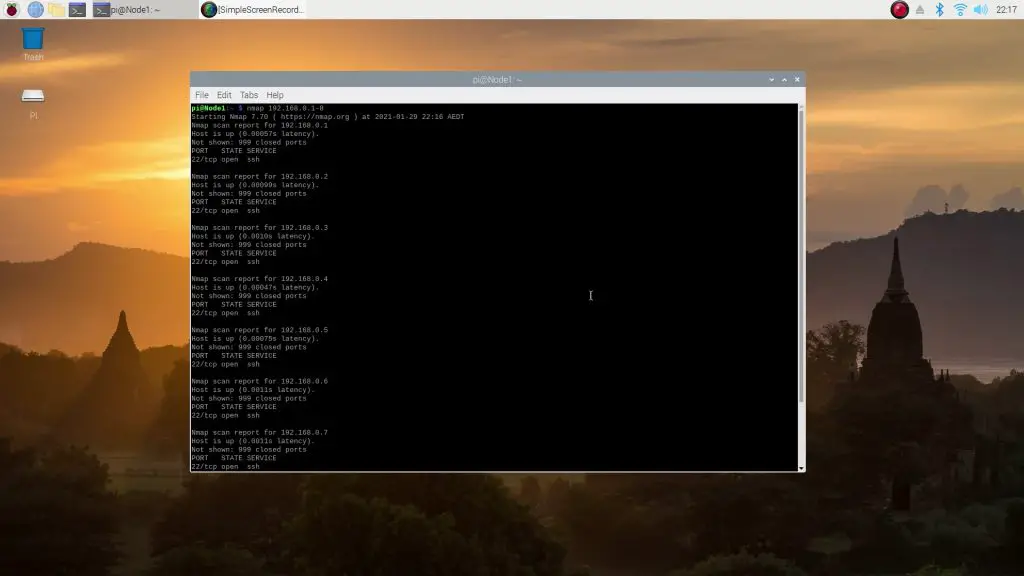

We can now use the NMAP utility to see that all 8 nodes are online:

nmap 192.168.0.1-8

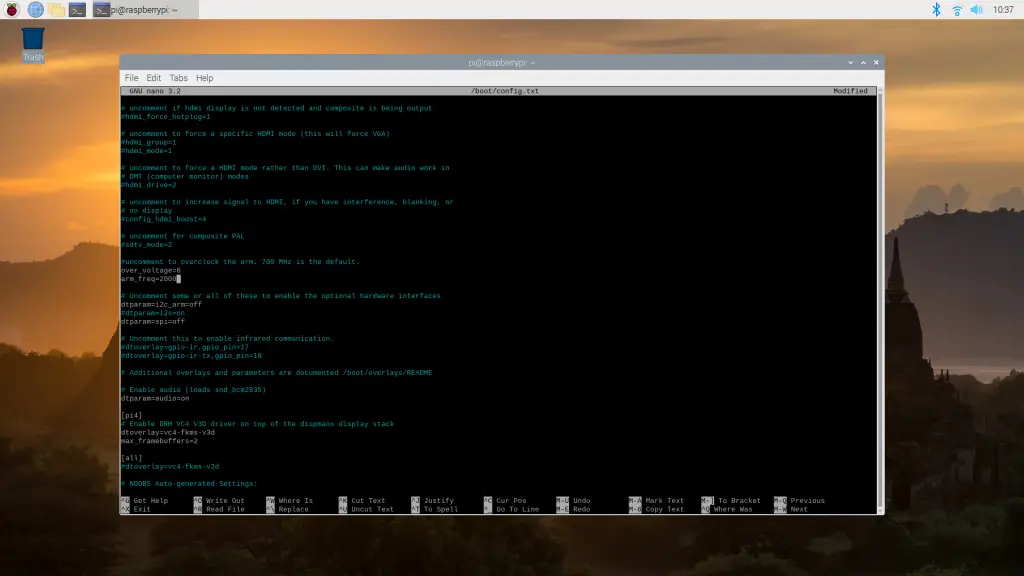

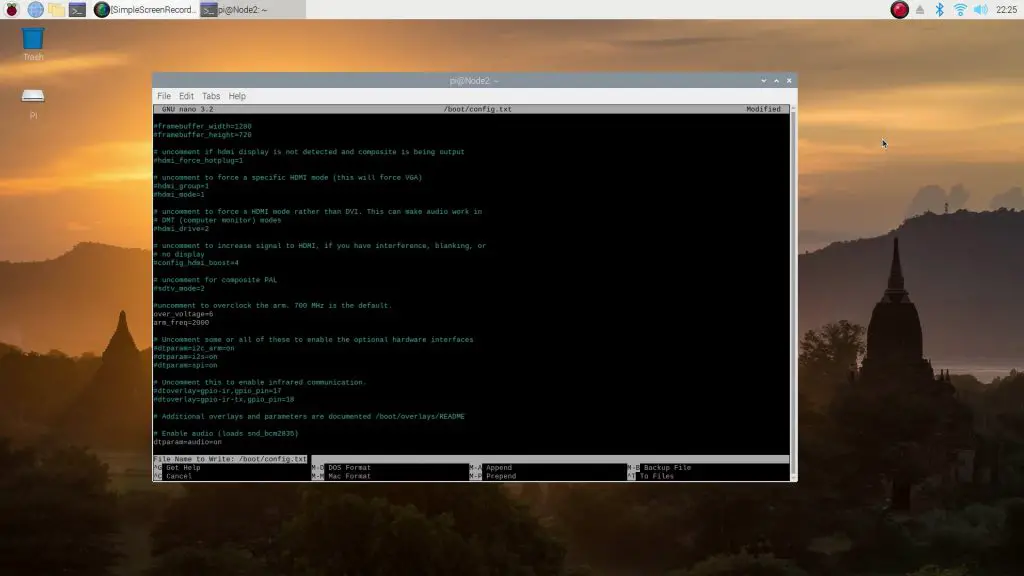

Overclock Each Node To 2.0 GHz

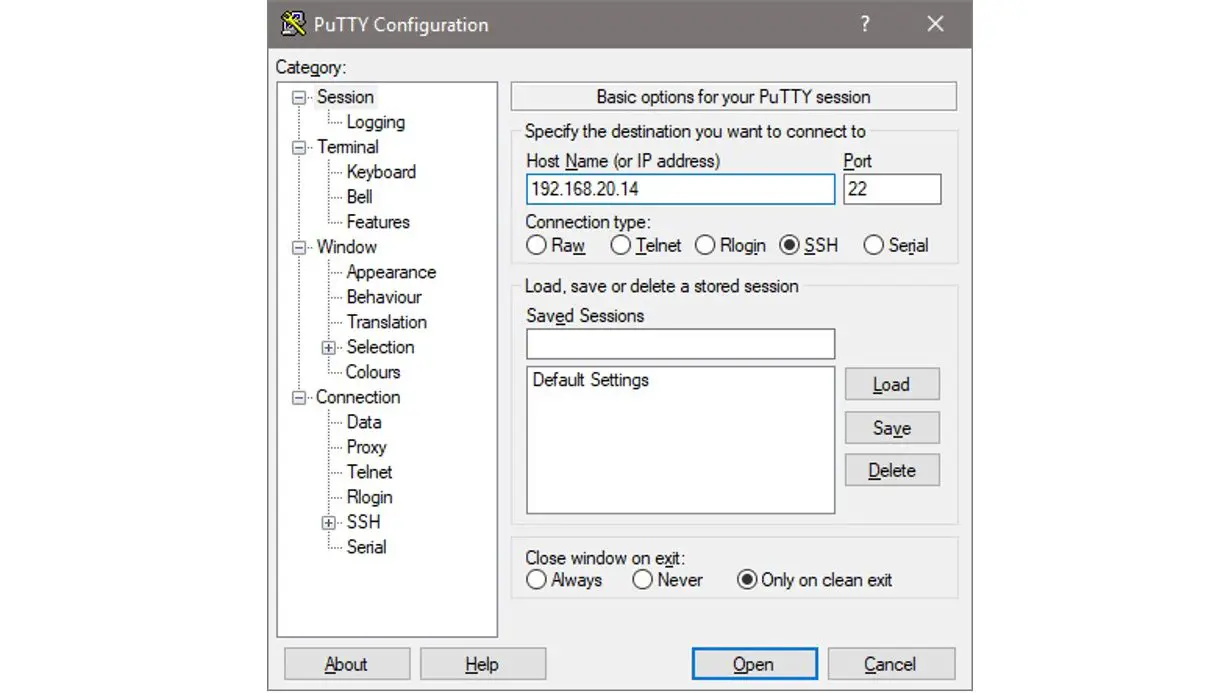

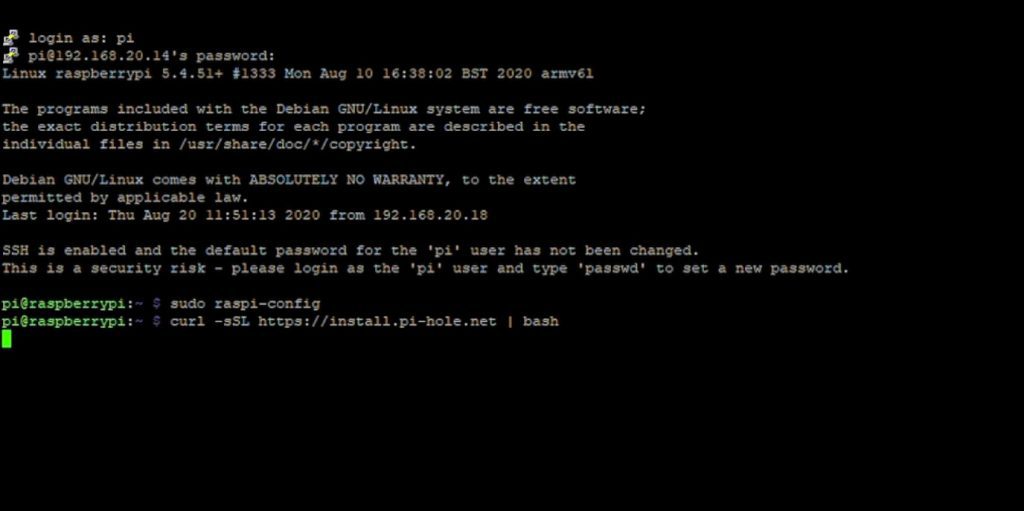

Next, we need to overclock each Pi to 2.0 GHz. I’ll do this from node 1 and SSH into each node to overclock it.

SSH into each Pi by entering into the terminal on Node1:

ssh pi@192.168.0.2You’ll then be asked to enter your username and password for that node and you can then edit the config file by entering:

sudo nano /boot/config.txtFind the line which says #uncomment to overclock the arm and then add/edit the following lines:

over_voltage=6

arm_freq=2000

Reboot each node once you’ve edited and saved the file.

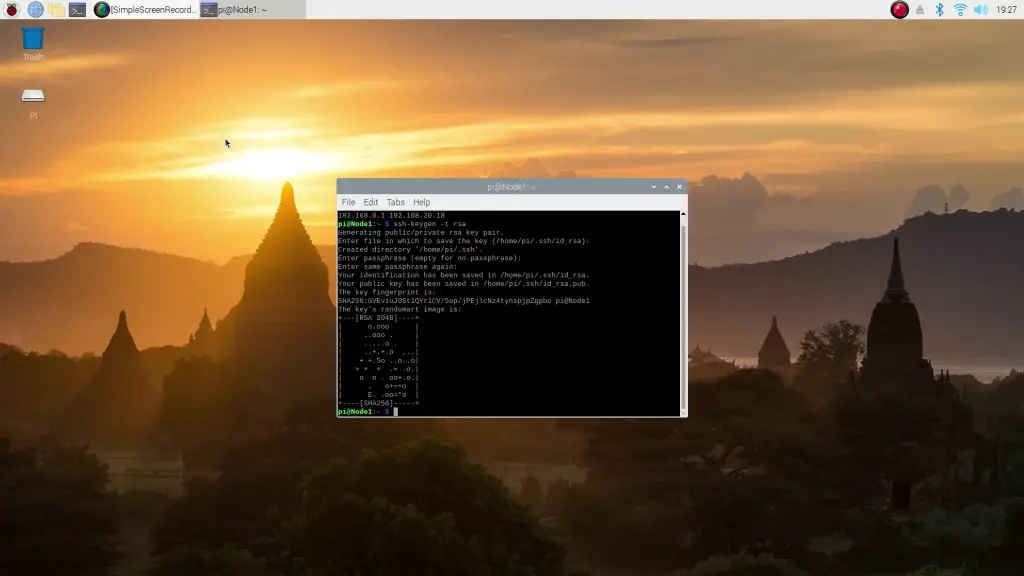

Create SSH Key Pairs So That You Don’t Need To Use Passwords

Next, we need to allow the Pis to communicate with the host without requiring a password. We do this by creating SSH keys for the host and each of the nodes and sharing the keys between them.

Let’s start by creating the key on the host by entering:

ssh-keygen -t rsa

Just hit ENTER or RETURN for each question, don’t change anything or create a passphrase.

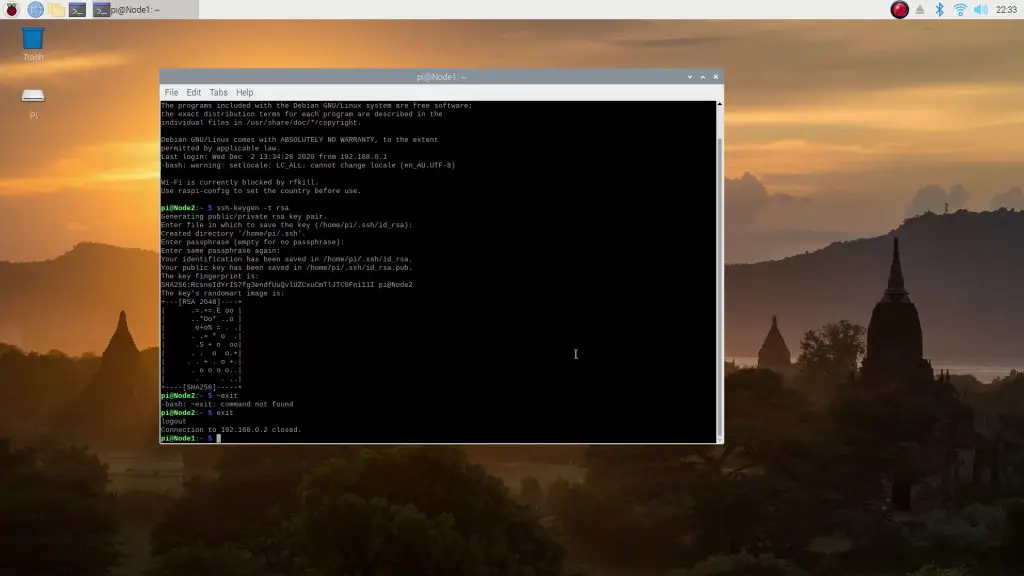

Next, SSH into each node as done previously and enter the same line to create a key on each of the nodes:

ssh-keygen -t rsa

Before you exit or disconnect from each node, copy the key which you’ve created to the master node, node 1:

ssh-copy-id 192.168.0.1Finally, do the same on the master node, copying it’s key to each of the other nodes:

ssh-copy-id 192.168.0.2You’ll obviously need to increment the last digit of the IP address and repeat this for each of your nodes so that the key is copied to all nodes.

This is only done in pairs between the host and each node, so the nodes aren’t able to communicate with each other, only with the host.

You should now be able to SSH into each Pi from node 1 without requiring a password.

ssh '192.168.0.2'Install MPI (Message Passing Interface) On All Nodes In The Raspberry Pi Cluster

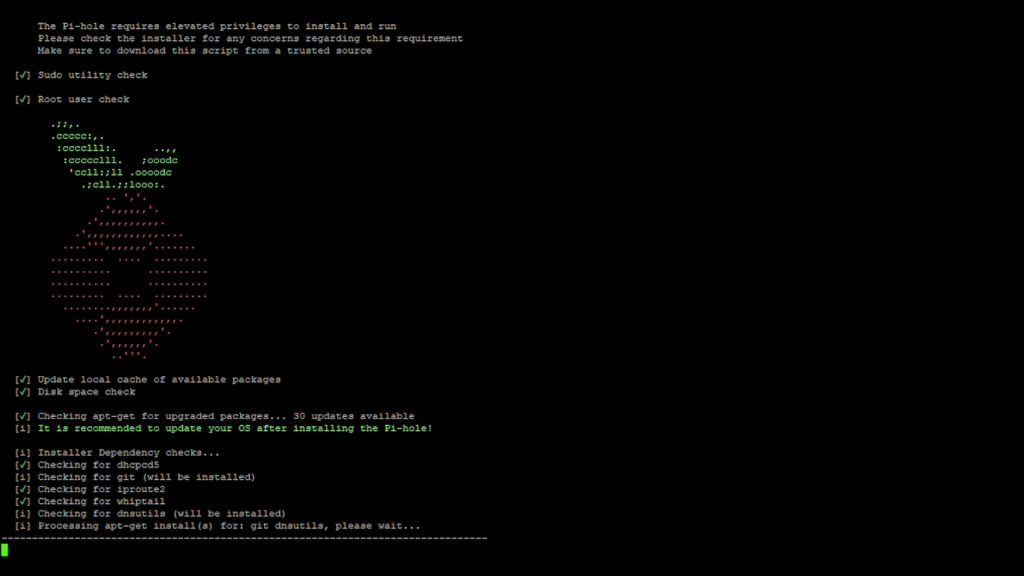

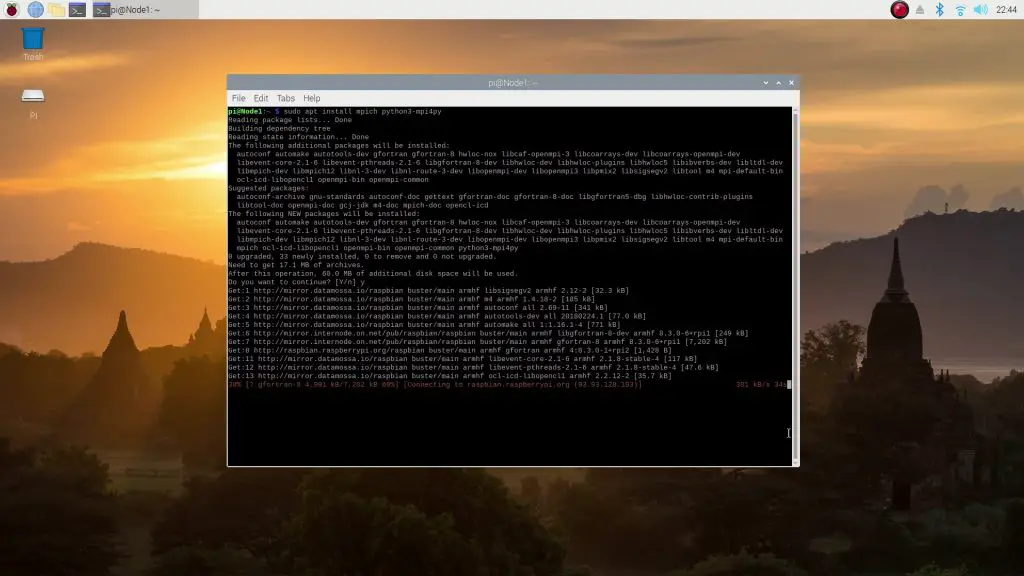

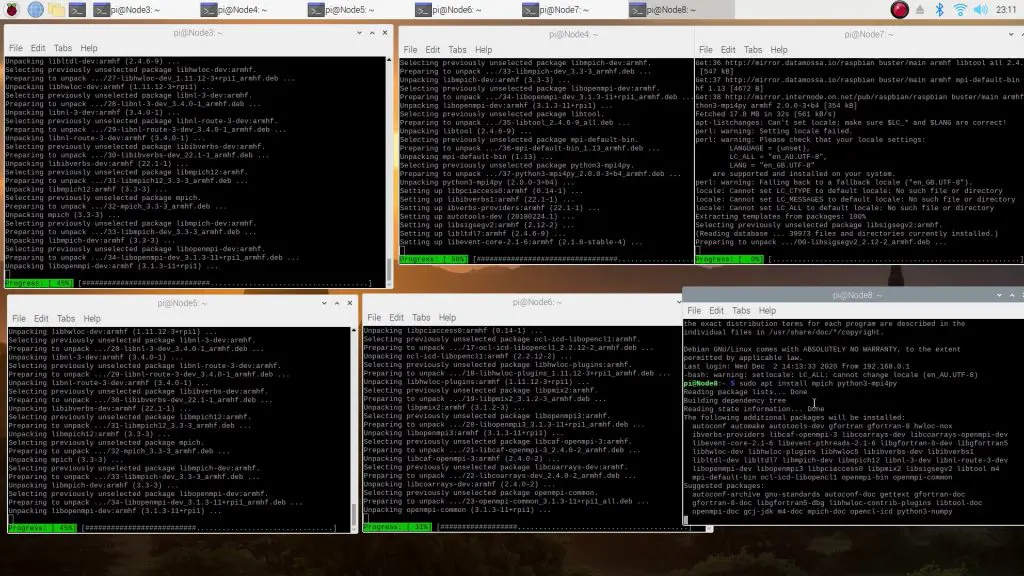

Next, we’re going to install MPI, which stands for Message Passing Interface, onto all of our nodes. This allows the Pis to delegate tasks amongst themselves and report the results back to the host.

Let’s start by installing MPI on the host node by entering:

sudo apt install mpich python3-mpi4py

Again use SSH to then install MPI onto each of the other nodes using the same script:

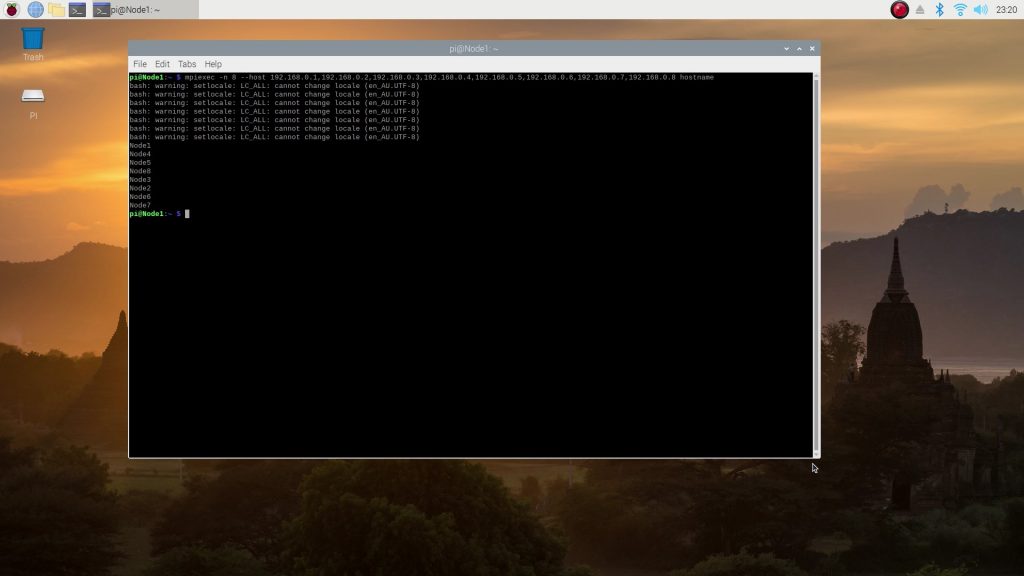

Once you’ve done this on all of your nodes, you can test that they’re all working and that MPI is running by trying the following:

mpiexec -n 8 --host 192.168.0.1,192.168.0.2,192.168.0.3,192.168.0.4,192.168.0.5,192.168.0.6,192.168.0.7,192.168.0.8 hostnameYou should get a report back from each node with it’s hostname:

Copy The Prime Calculation Script To Each Node

The last thing to do is to copy the Python script to each of the Pis, so that they all know what they’re going to be doing.

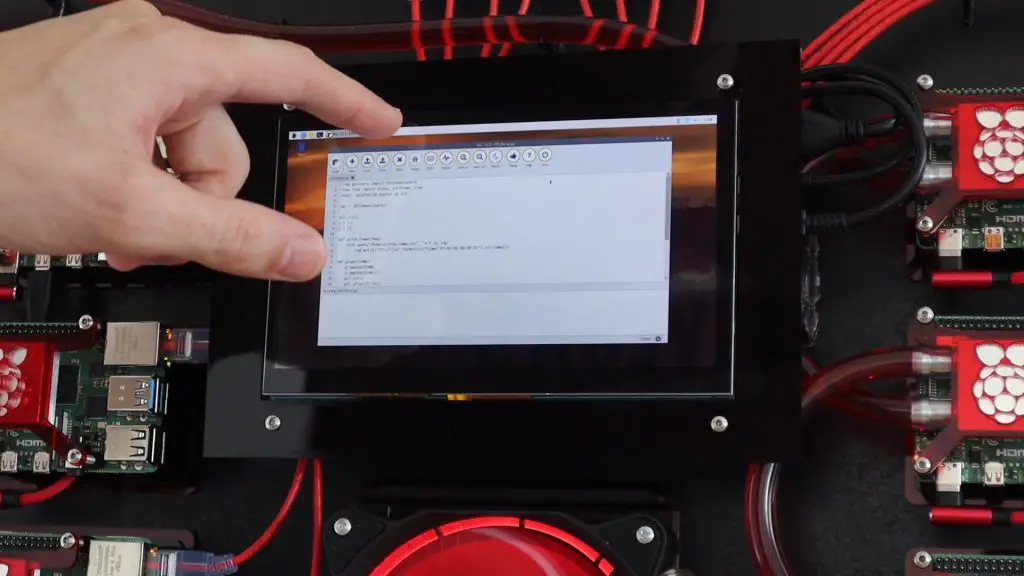

Here is the script we’re going to be running on the cluster:

The easiest way to do this is with the following line:

scp ~/prime.py 192.168.0.2:You’ll again obviously need to increment the IP address for each node, and the above assumes that the script prime.py is in the home directory.

You can check that this has worked by opening up an SSH connection on any node and trying:

mpiexec -n 1 python3 prime.py 1000Once this is working, then we’re ready to try out our cluster test.

Testing The Raspberry Pi Cluster

We’ll start out with calculating the primes up to 10,000. So we’ll start a cluster operation with 8 nodes, list the node’s IP addresses and then tell the operation what script to run, in which application to run it and finally the limit to run the test up to:

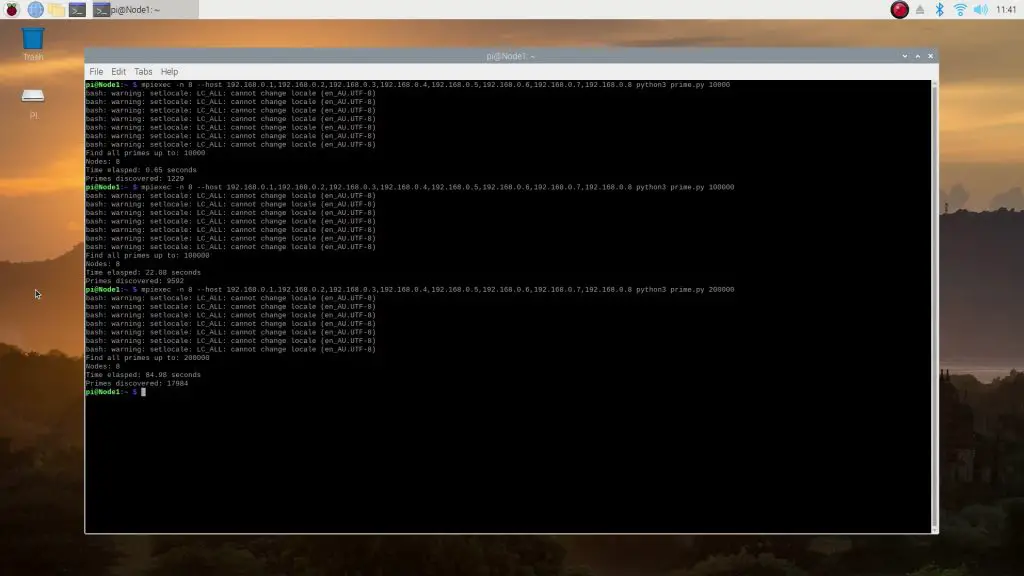

mpiexec -n 8 --host 192.168.0.1,192.168.0.2,192.168.0.3,192.168.0.4,192.168.0.5,192.168.0.6,192.168.0.7,192.168.0.8 python3 prime.py 10000The cluster was able to get through the first 10,000 in 0.65 seconds – faster than either of our computers. Which is quite surprising given that the system needs to manage communication to and from the nodes as well.

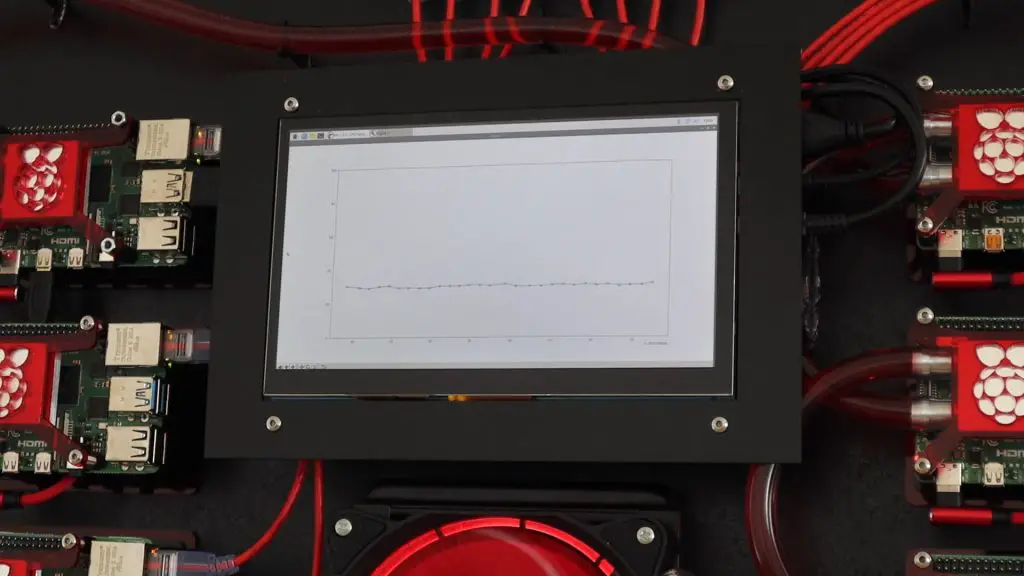

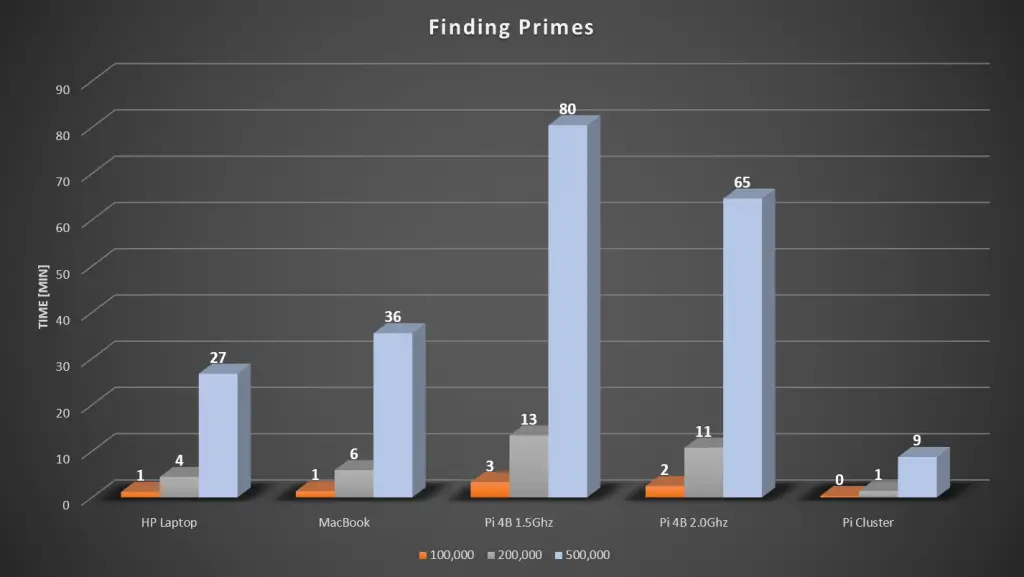

Here are the results for the test to 10,000, 100,000 and then to 200,000:

The search to 200,000 took just 85 seconds, which is again a little over 3 times faster than the Windows PC and 4 times faster than the MacBook. It was also a just a little slower than 8 times faster than the individual Pi.

Here is a comparison of the combined results from all of the tests done:

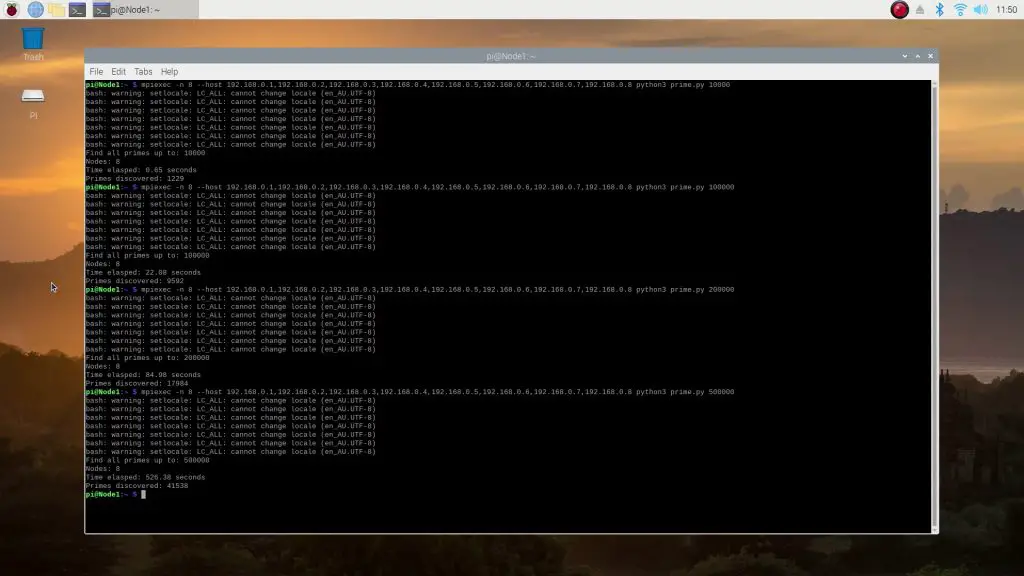

Lastly, I just ran the simulation to 500,000 on the cluster to see how fast it would be.

That took 526 seconds, or a little under 9 minutes.

I plotted a trend and forecast the 500,000 times for the other tests so that you can see how they compare. I’ve converted all of these values to minutes to make them a bit more understandable.

So our cluster was able to beat the PC and Mac quite significantly, which might be somewhat surprising, but that is the power of cluster computing. You can imagine that when running really large simulations, which often take a couple of days on a PC, being able to run the simulation just 2-3 times faster is a massive saving. A week-long simulation on the PC can be completed by the Pi Cluster in just two and a half days.

Now obviously we could cluster PCs as well to achieve better simulation times, but remember that each Pi node in this setup costs just $35, so you can build a pretty powerful computer for a few hundred dollars using Raspberry Pis. You’re also not limited to just 8 nodes, you could add another 8 nodes to this setup for around $400 and you’d have a cluster which performs 6 times faster than the PC.

Multi-Process Test Results

As mentioned in an earlier edit in the post, Adi Sieker put together a multi-process version of the script.

Here are the results of the tests done so far (I’ll keep adding to them as I complete them on each platform):

HP Laptop – Using 16 processes:

- 10,000 – 0.9 s

- 100,000 – 18.27 s

- 200,000 – 66.99 s

- 500,000 – 374.3 s (6 mins 15 s)

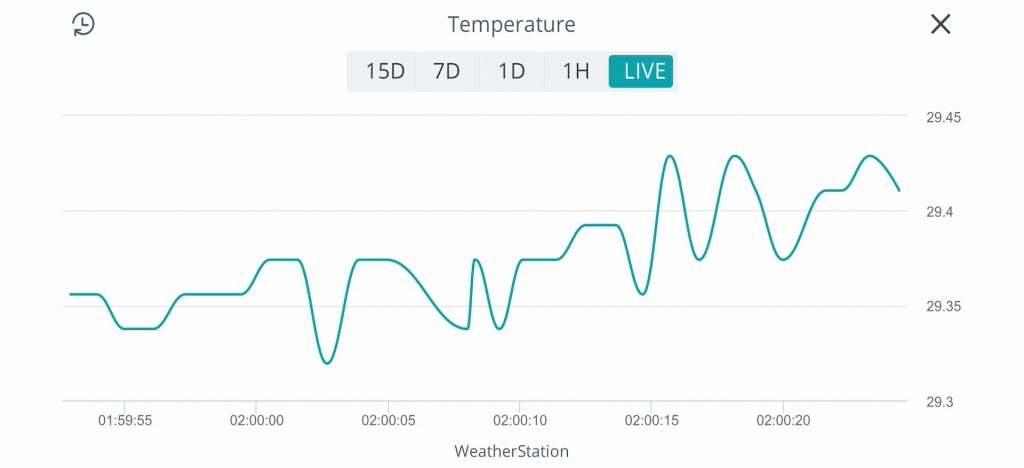

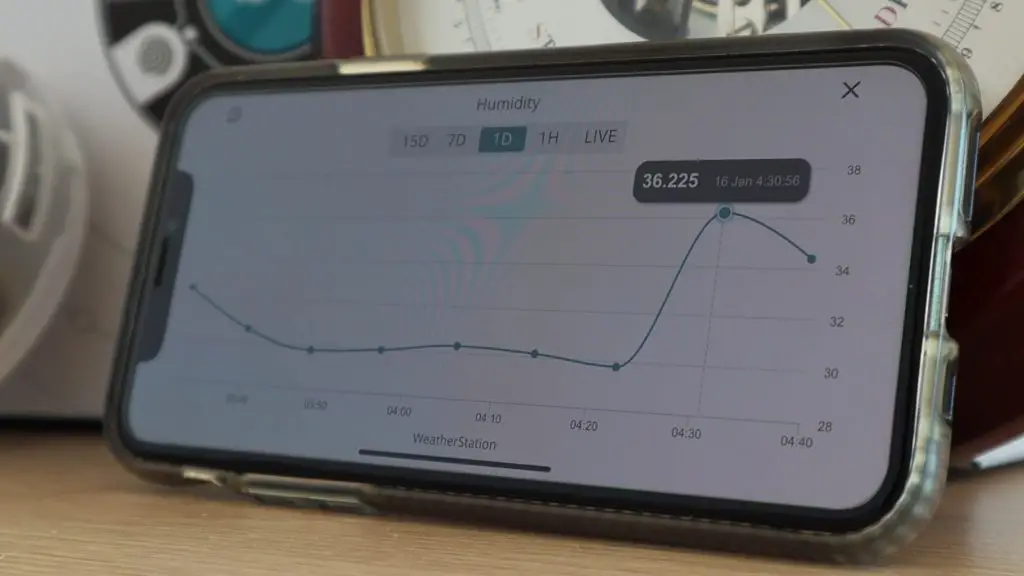

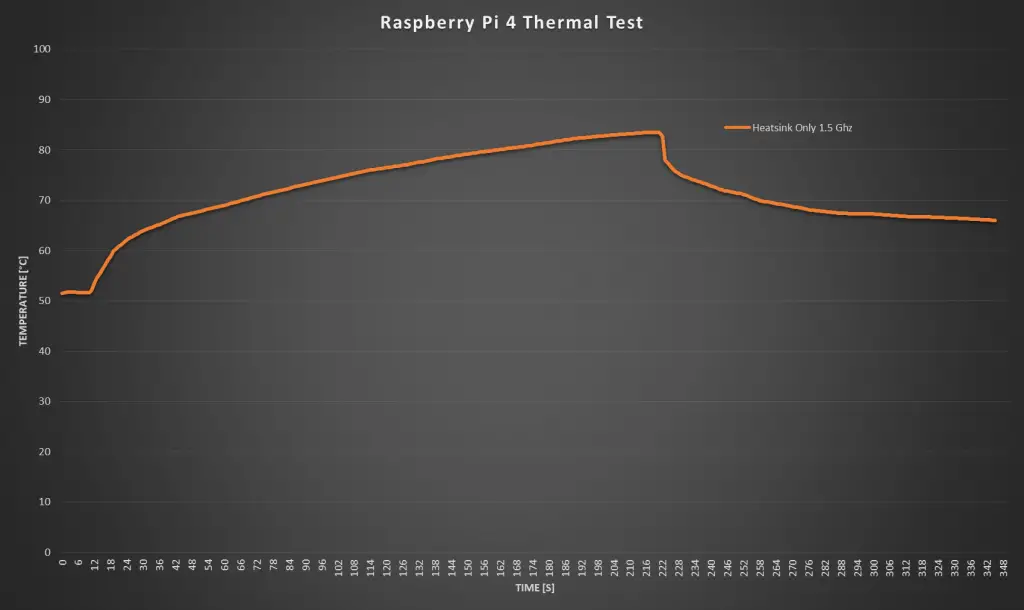

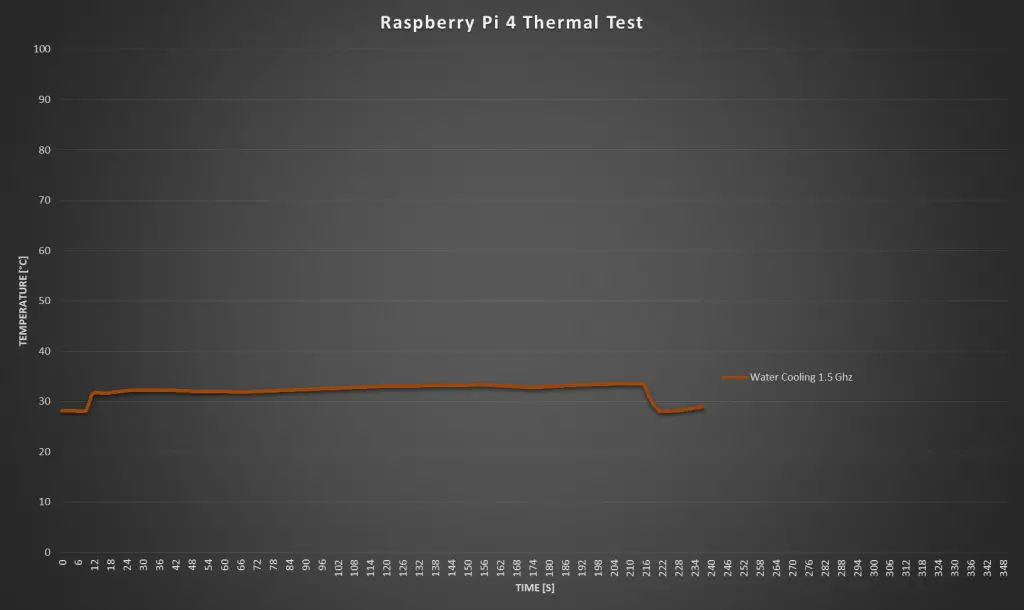

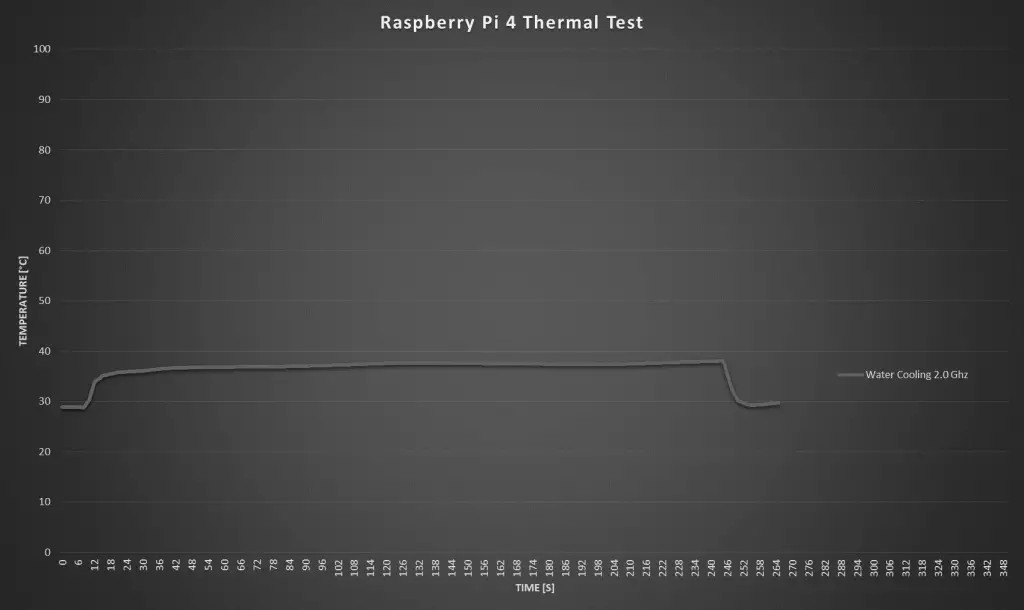

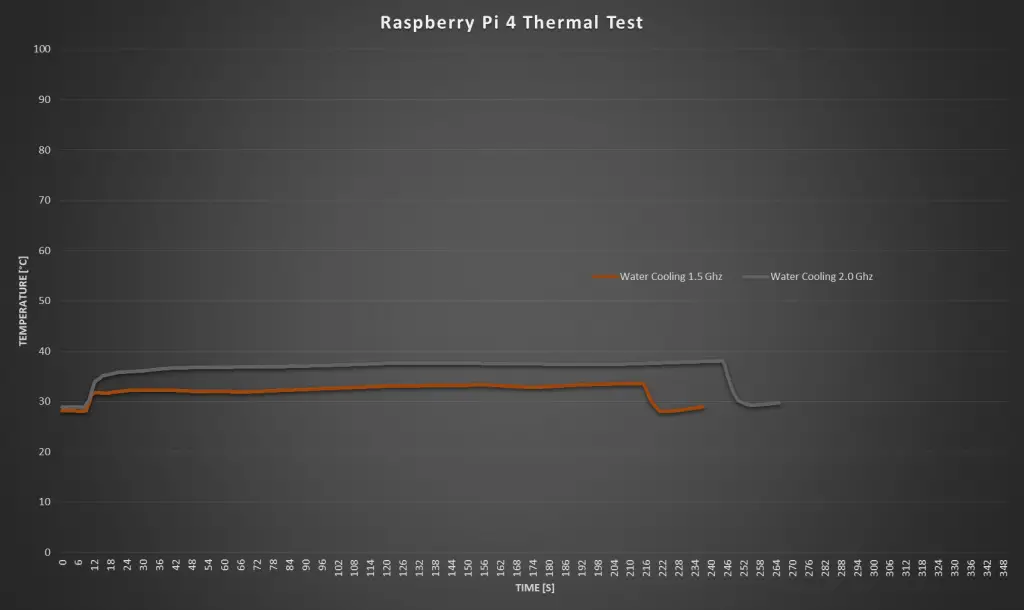

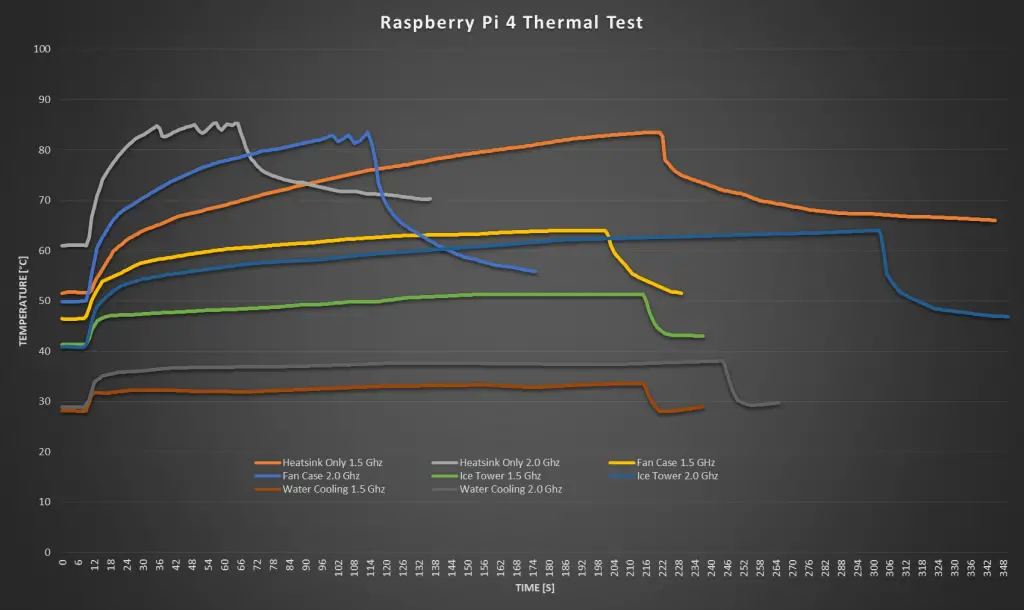

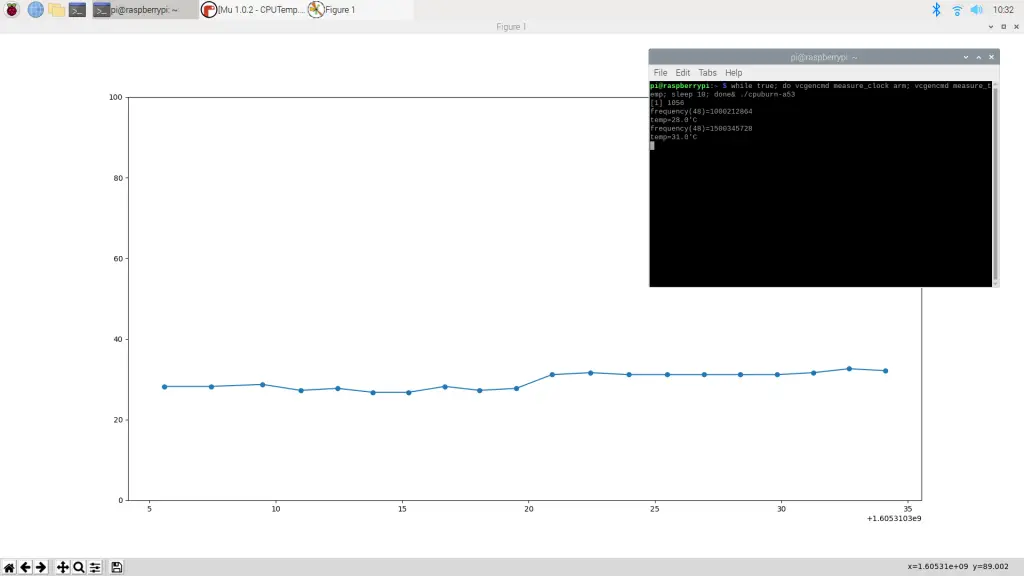

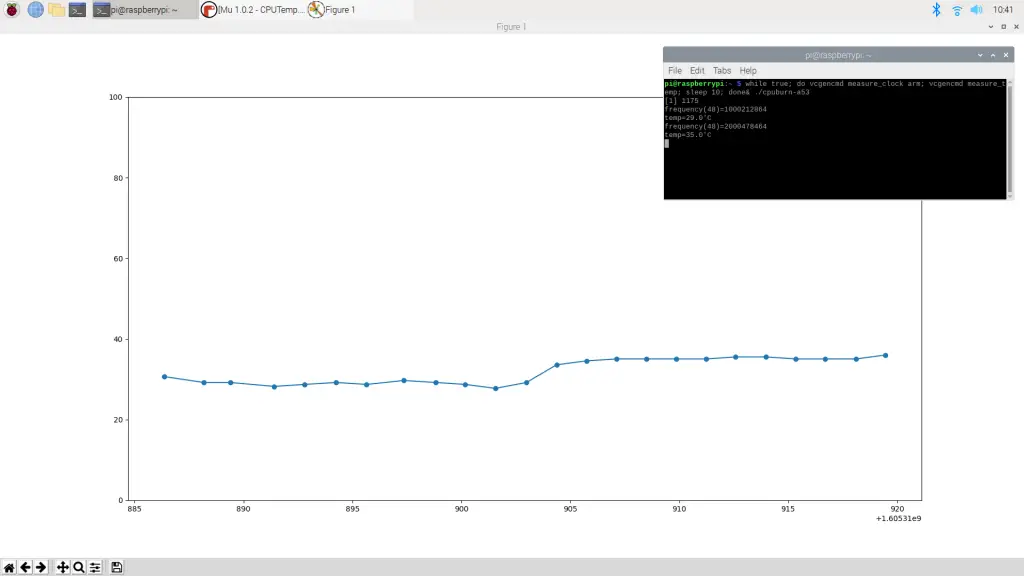

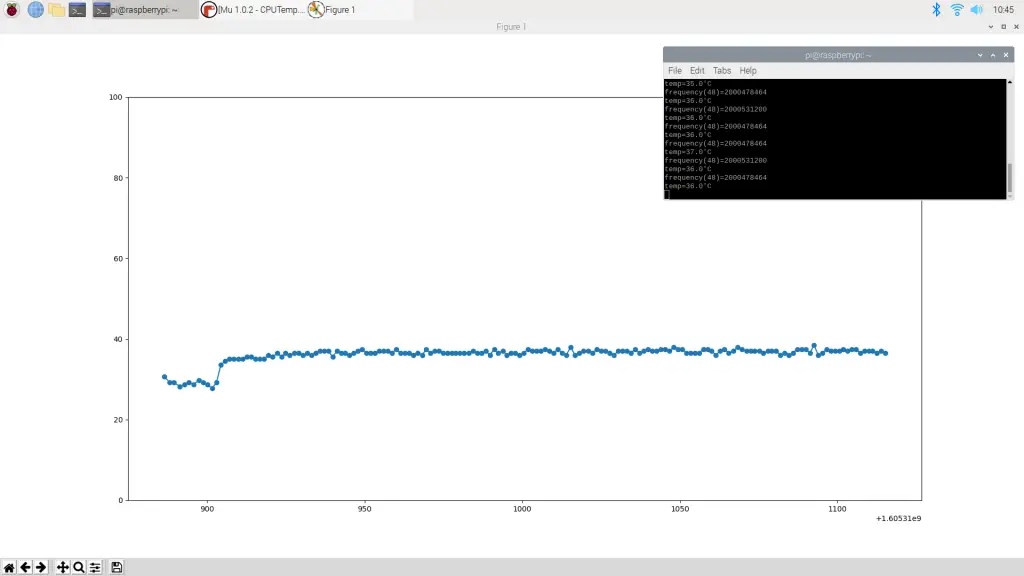

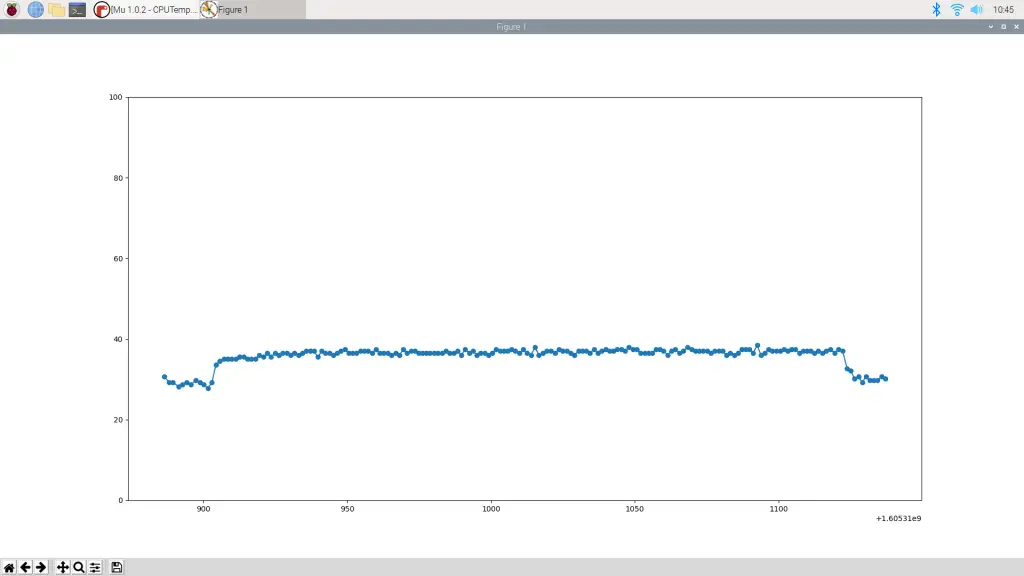

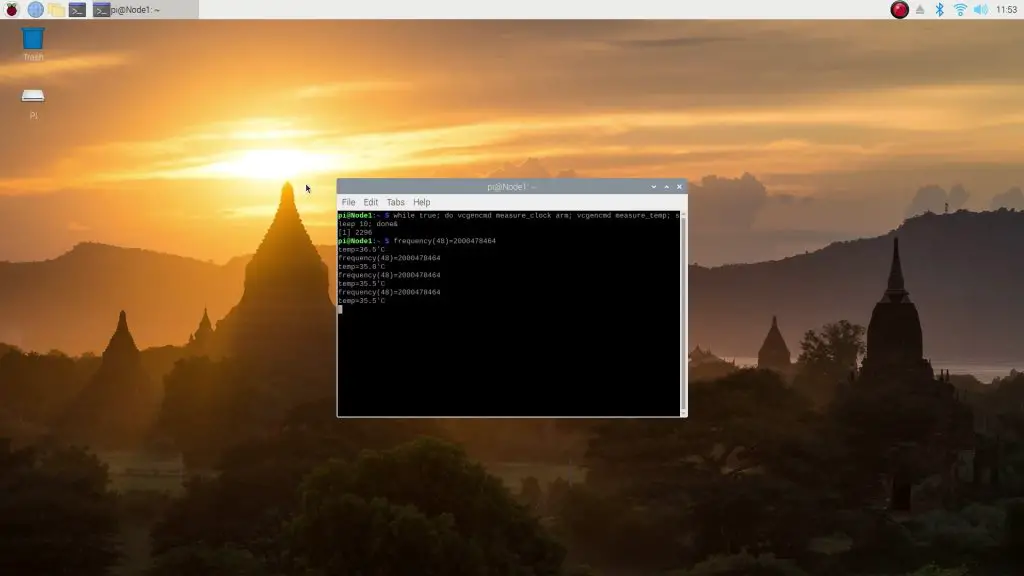

What About The Temperature Of The Loop?

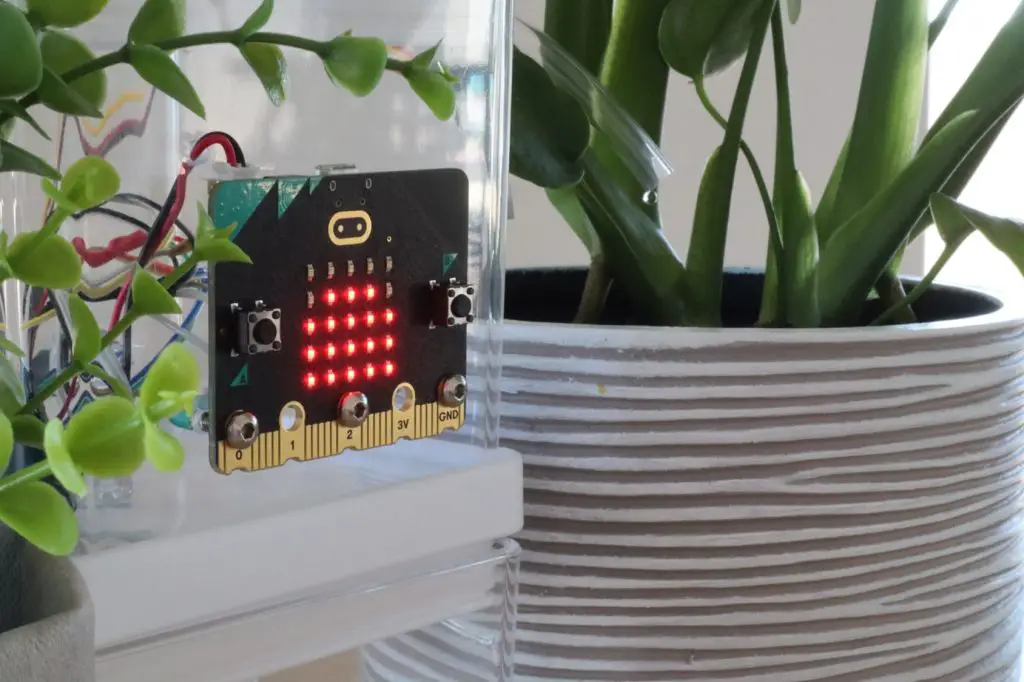

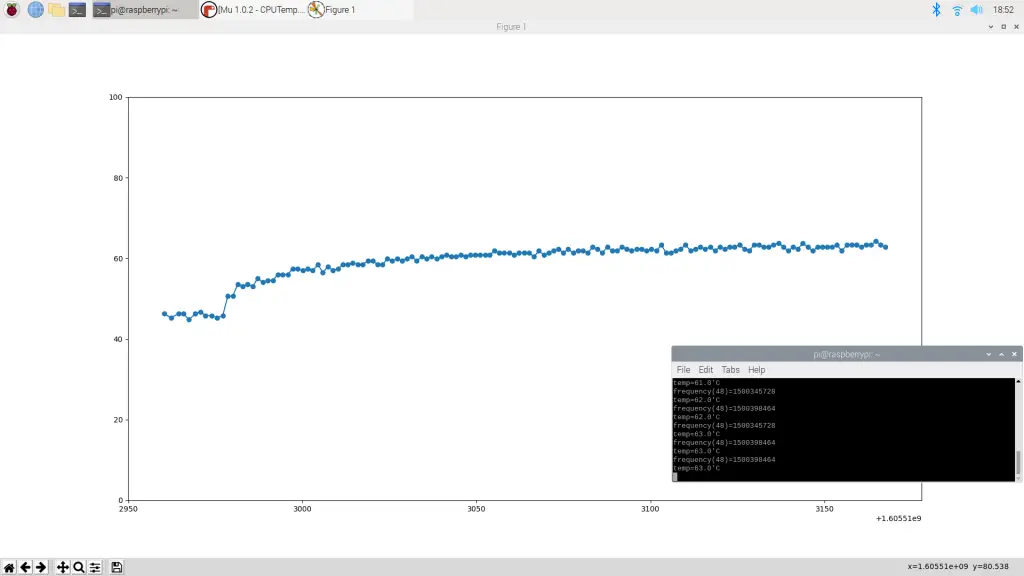

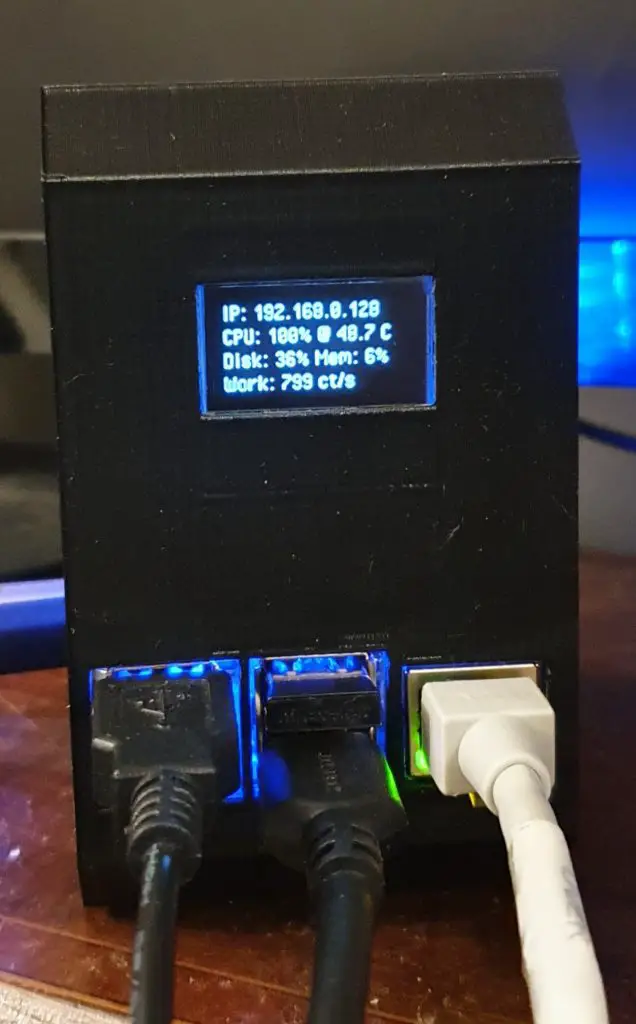

I also checked the temperature of the master node, which is midway through the cooling loop (5th in the loop), to see how warm it was after the test:

It was only around 8 degrees above room temperature after the test.

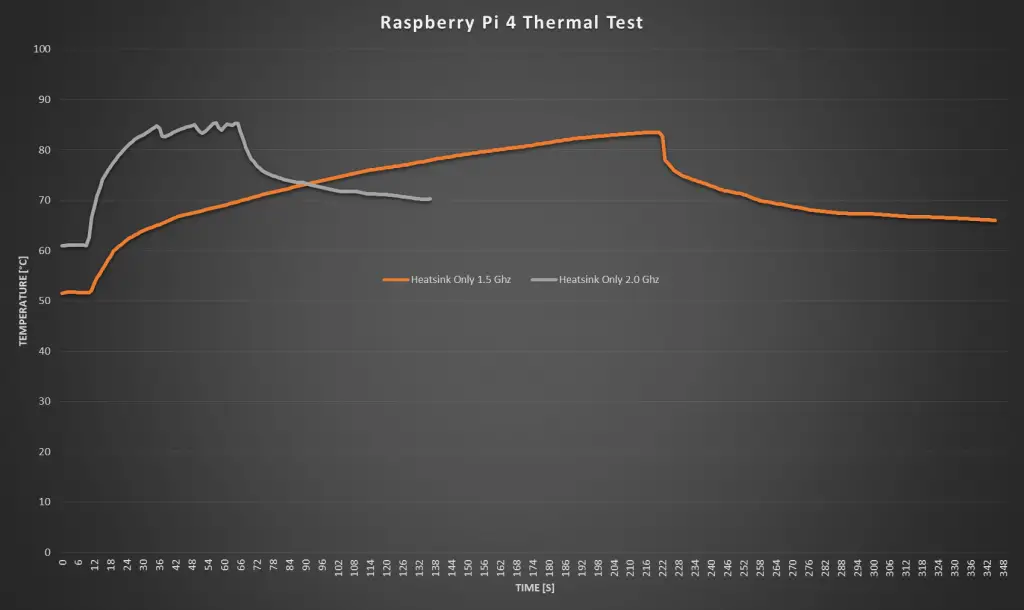

Next, I’m going to be doing a full thermal test on the Raspberry Pi Cluster to check how it performs under full load for a duration of time. So be sure to check back in a week or two or subscribe to my channel for updates on Youtube.

As mentioned earlier, feel free to download the script and try it out on your own computer and share your results with us in the comments section. We’d love to see how some other setups compare.