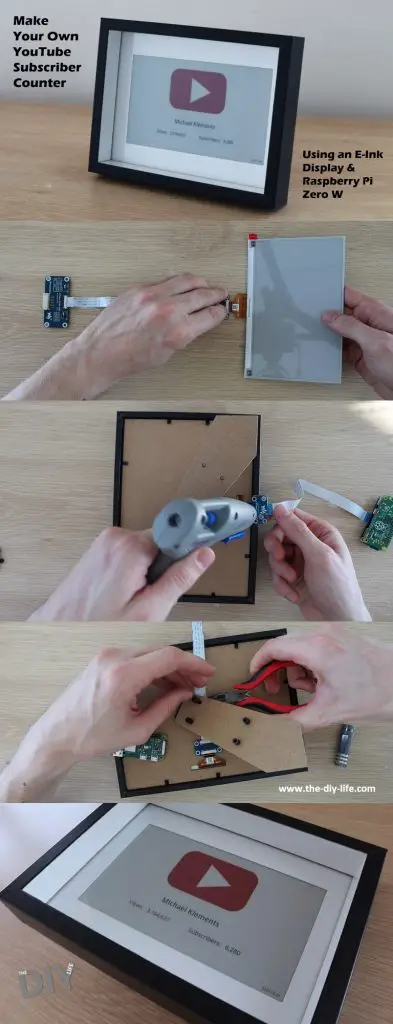

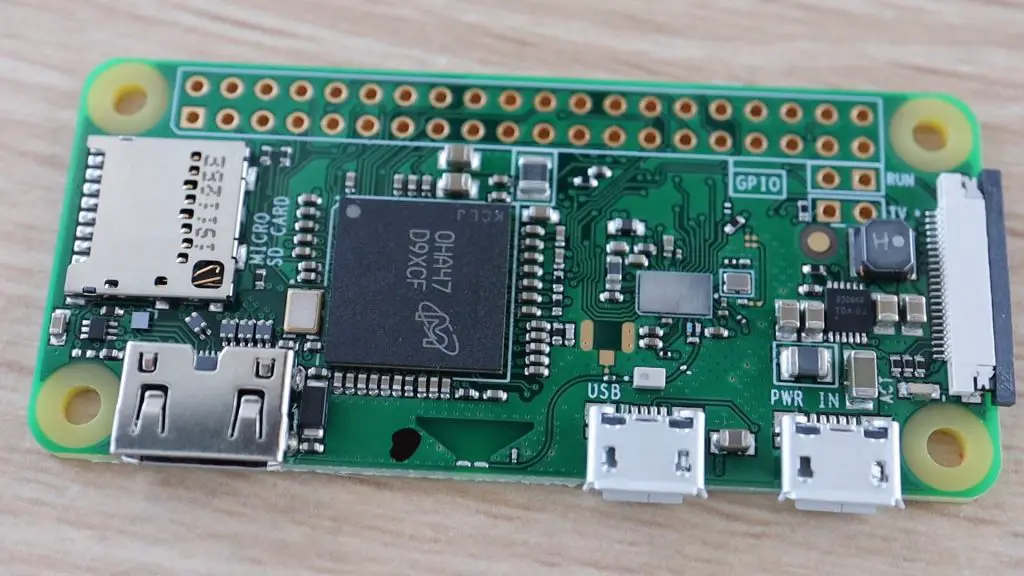

I’ve seen a couple of different designs for YouTube subscriber counters and social media follower counters and I had a Raspberry Pi Zero W lying around which I wanted to put to use. I didn’t want the distraction of a bright LCD display at night, so an e-ink or e-paper display seemed like the best option. So, in this project, I’ll show you how to make your own Youtube Subscriber Counter using a 7.5” Waveshare E-Ink display and a Raspberry Pi Zero W to update it.

The Raspberry Pi uses a Python script to query the YouTube API a couple of times a day and then refreshes the e-ink display to update the counter. It’s really simple to make as it just uses the Waveshare Hat for Raspberry Pis, so there is no soldering required and you don’t have to worry about tinkering with any other electronics to get it working.

The e-ink display provides great visibility during the day, even in bright light, and only uses power when it’s being refreshed, so the counter uses very little power to run. The updates take about 40 seconds to complete and between updates the Pi uses around 0.5W while at idle.

Here’s a video of the build and the display updating, read on for the step by step instructions to build your own.

What You Need To Make Your Own Youtube Subscriber Counter

- Raspberry Pi Zero W – Buy Here

- Micro SD Card – Buy Here

- Waveshare 7.5” HD E-Ink Display (B) With Controller – Buy Here

- 6×8” Shadow Box Frame – Buy Here (The one linked to is not exactly the same as used in the project, but the most similar I could find on Amazon)

- Keyboard, Mouse & Monitor For Setup (Or Connect Through SSH)

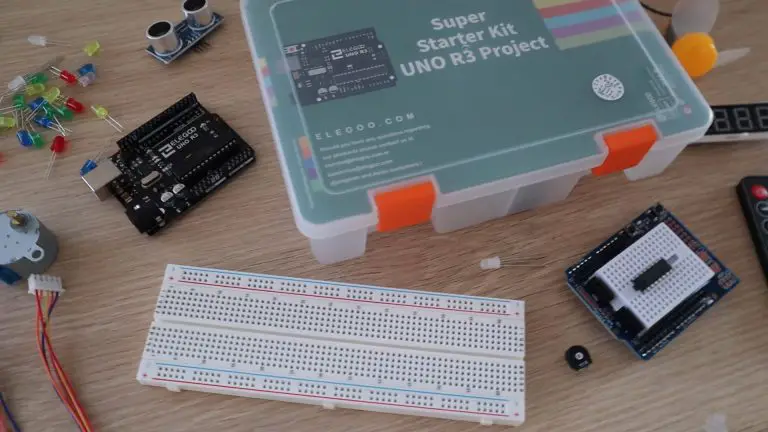

All you need for this project is a Raspberry Pi Zero W, an SD card, and a Waveshare E-Ink Display, make sure that you order the display which includes the hat display controller for the Raspberry Pi. You’ll also need a suitable frame to put it in, you may even have one lying around your home.

Connect & Prepare The Electronics For Your YouTube Subscriber Counter

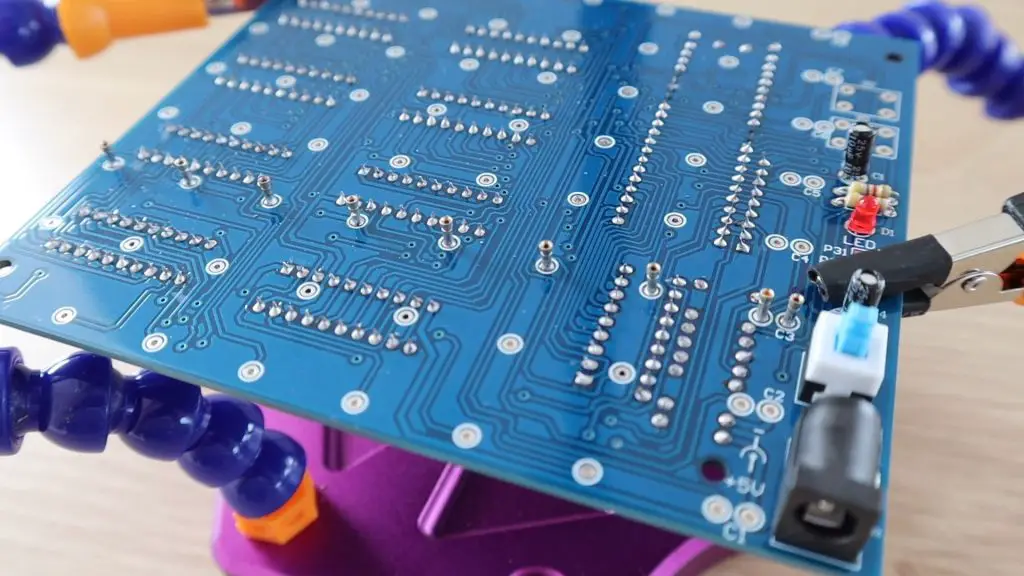

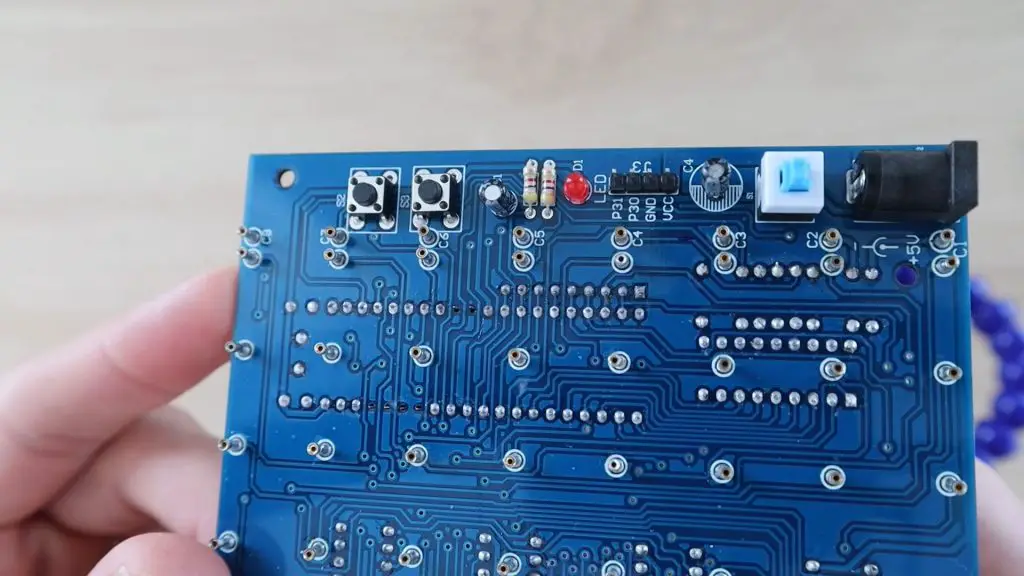

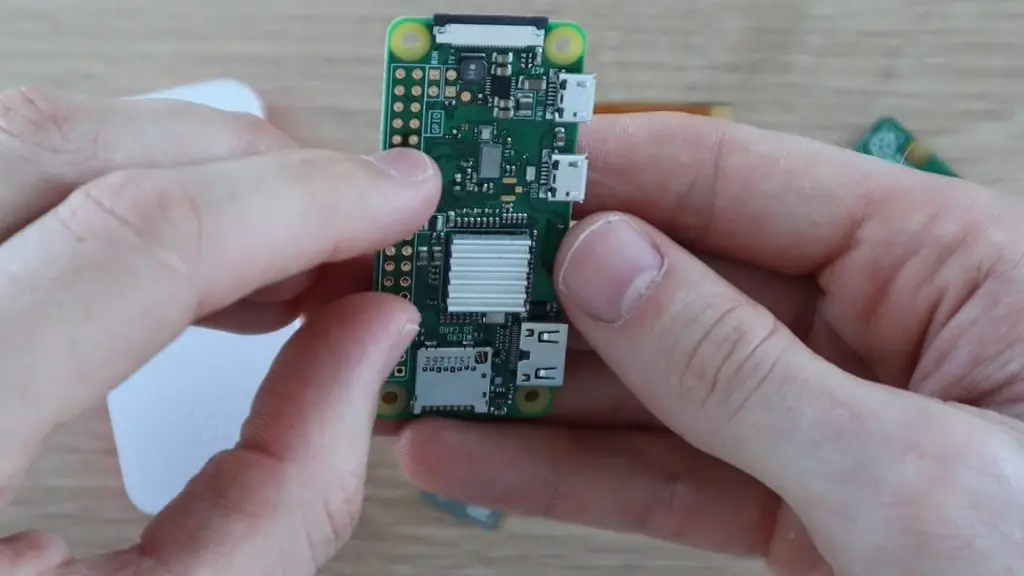

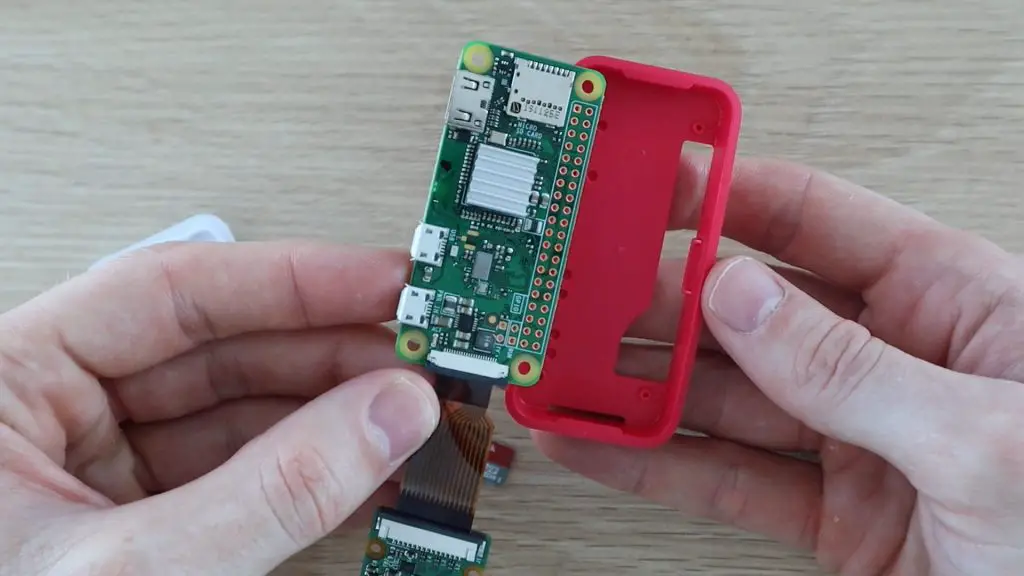

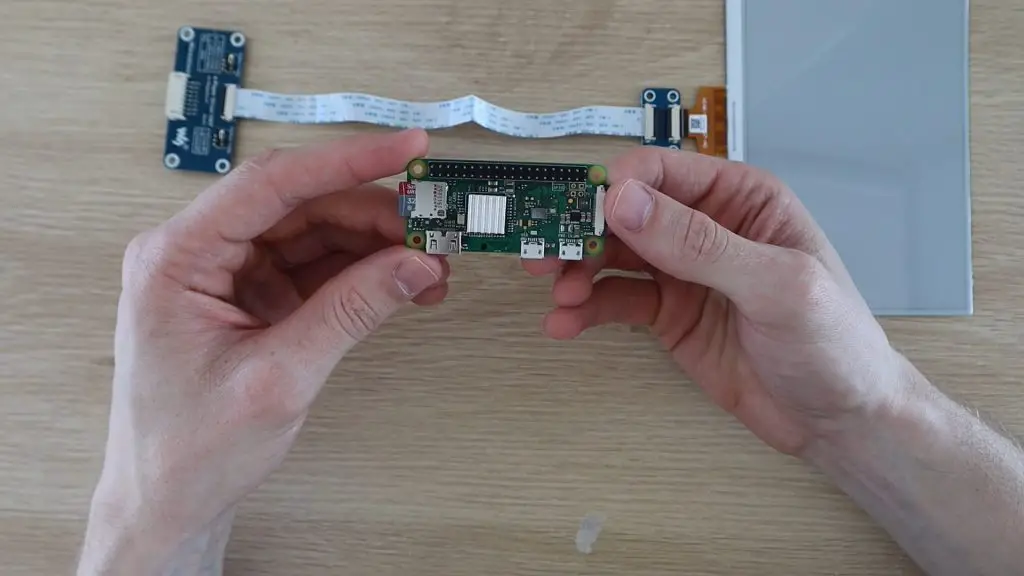

Let’s start by preparing the Raspberry Pi Zero W. You’ll need the header pins to be soldered to your Pi Zero, so if yours didn’t come with them already installed, then you’ll need to install them before starting. Also, attach the heat sink to the CPU, this project isn’t particularly strenuous on the CPU, but it’s a good idea to install it anyway.

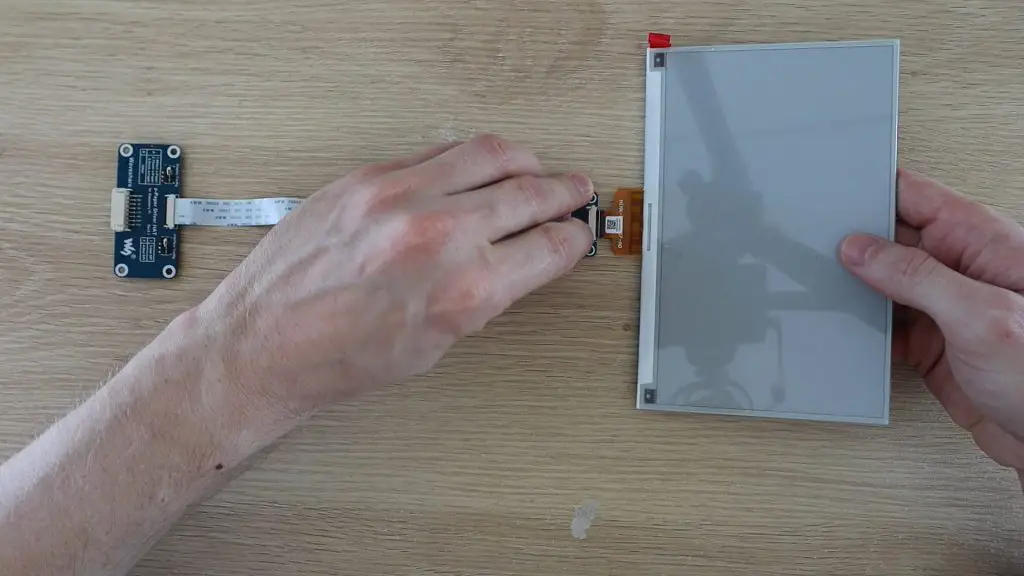

Once your Pi is prepared, you can connect the display. I’ve used the 7.5” HD 3 colour version, the three colours being white, black and red. You also get a two colour version which is just black and white and another 3 colour version which had yellow instead of red. The red just works better for the YouTube play button.

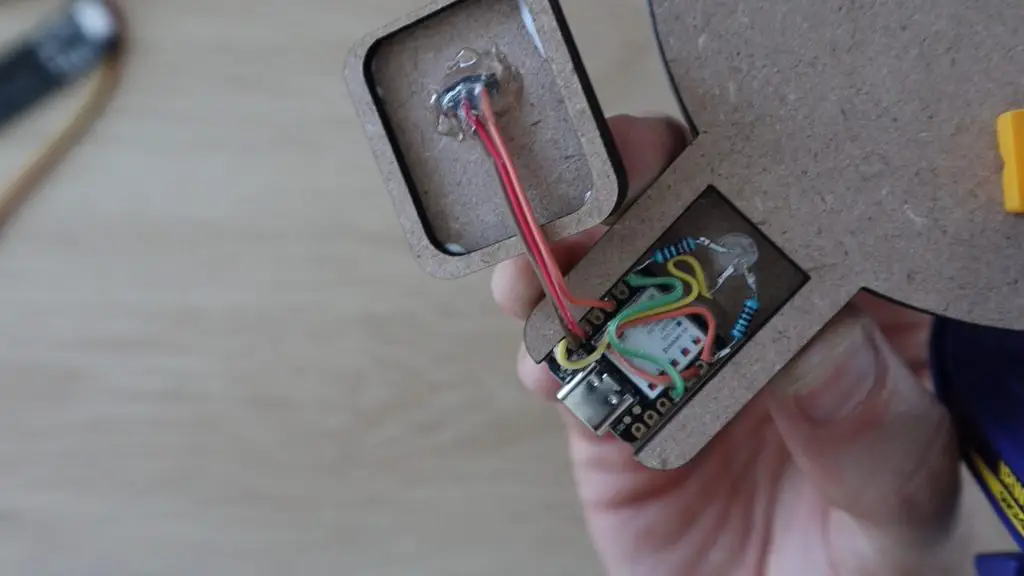

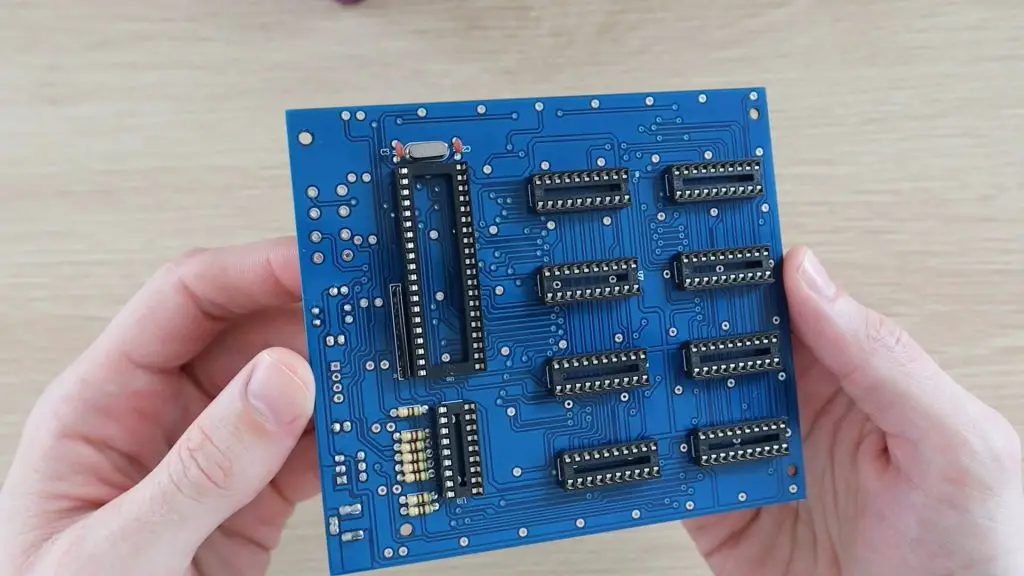

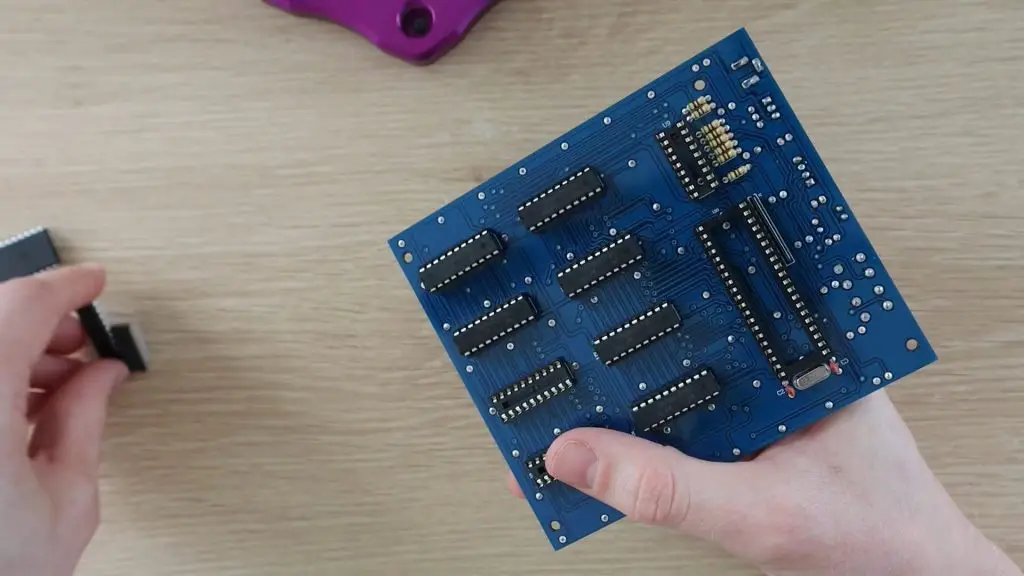

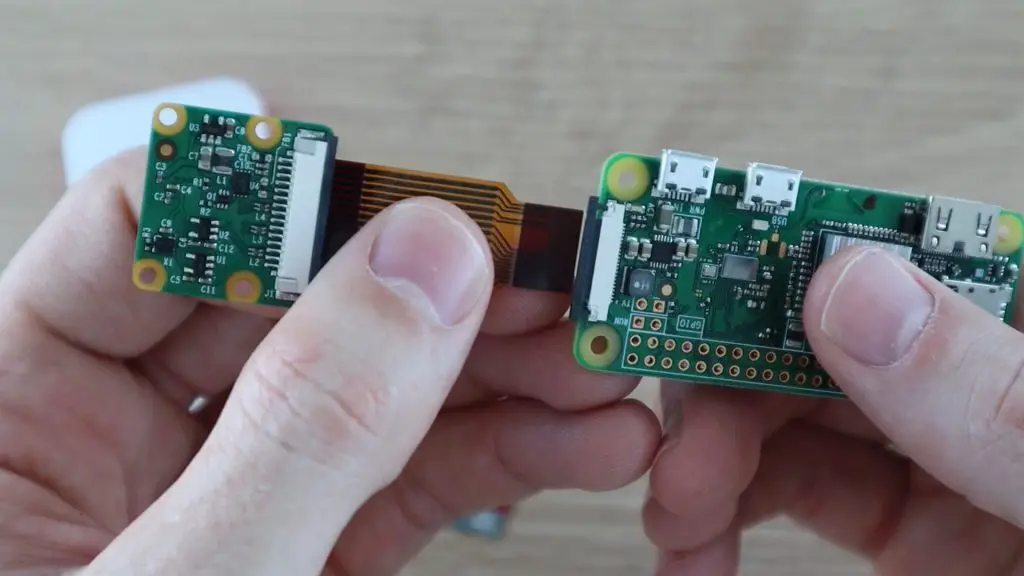

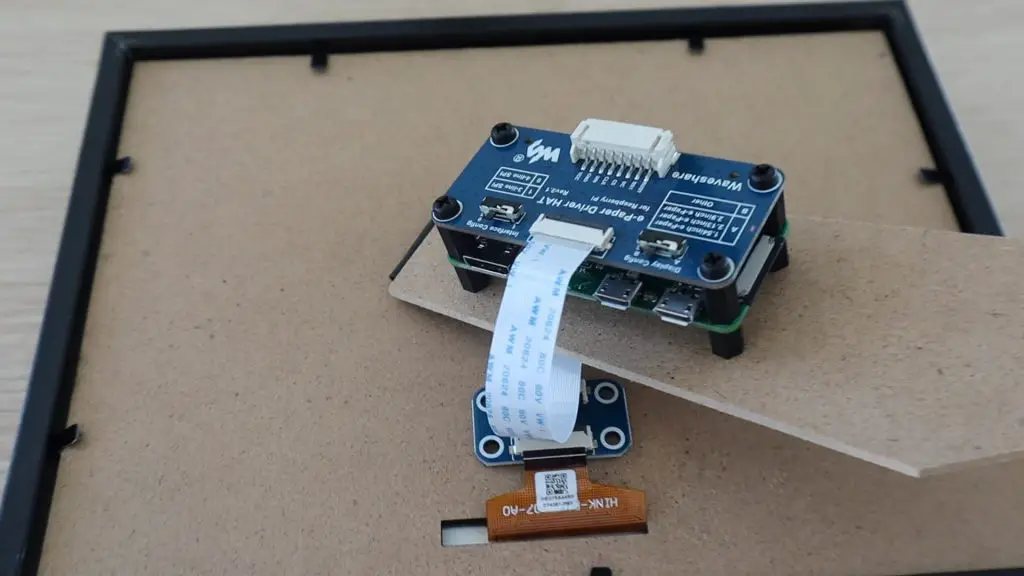

In the box, you get the SPI e-paper display controller, which is designed as a Raspberry Pi hat, to plug directly onto the GPIO pins. It also includes a plug and a set of leads to connect the controller to another SPI capable device, such as an Arduino or ESP32.

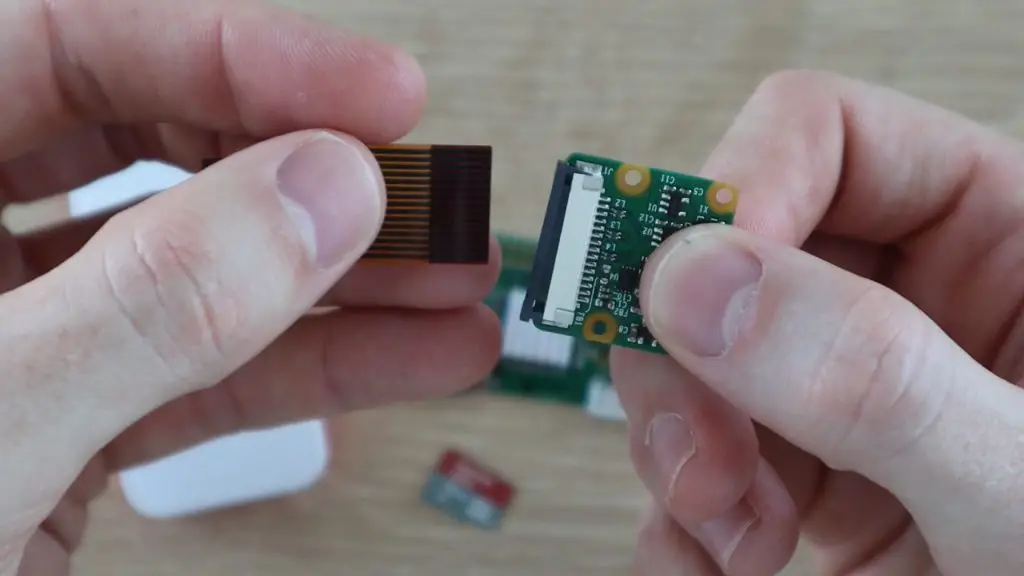

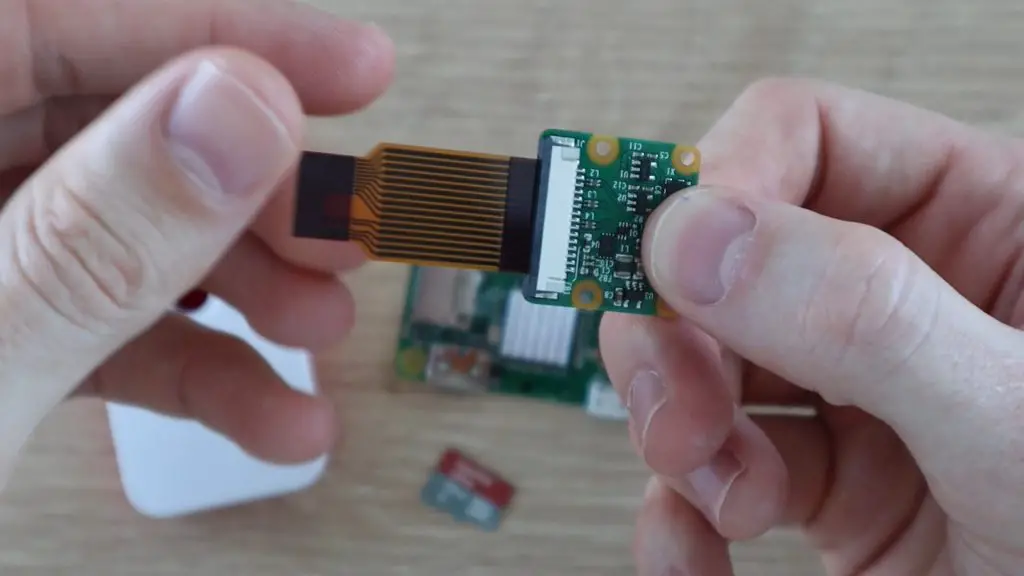

The actual display is really thin and has a thin ribbon cable at the bottom which plugs into the controller.

To connect the electronics together, you simply lift the black tab on the back of the connector, plug the display’s ribbon cable into the connector and then push the black tab down to lock it into place. Make sure that you get the orientation of the plug correct, the components are all face-up when laid on a flat surface.

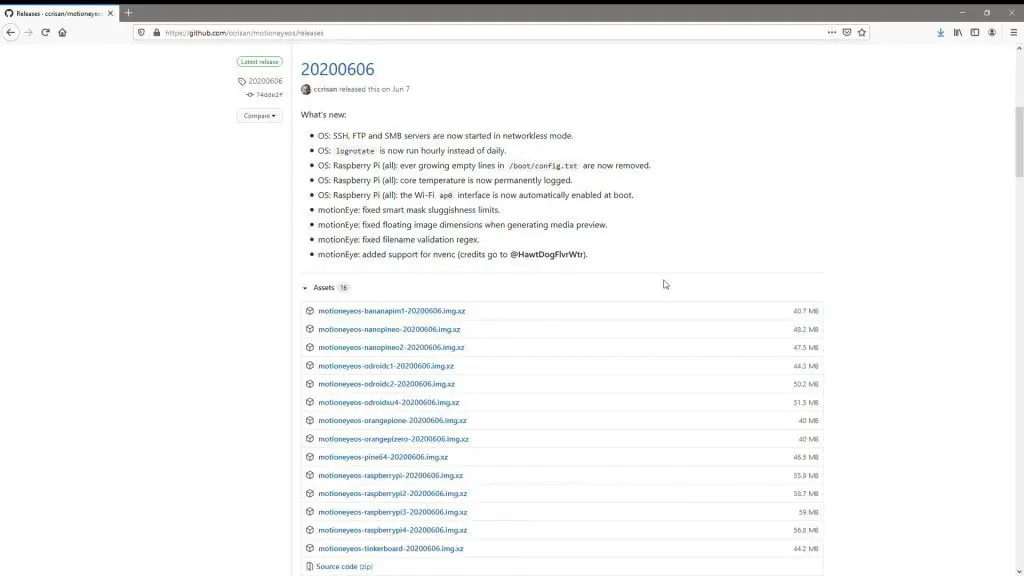

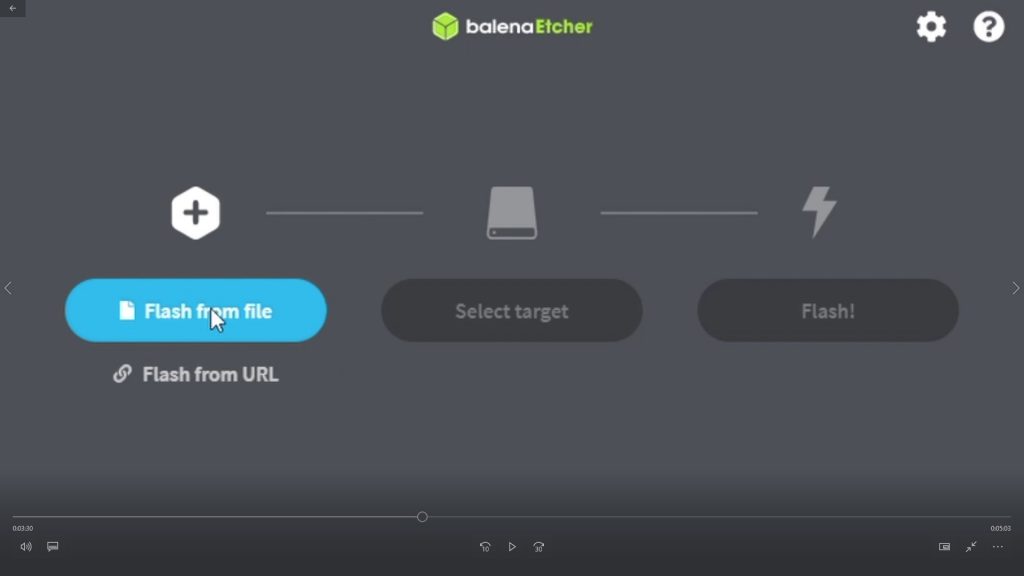

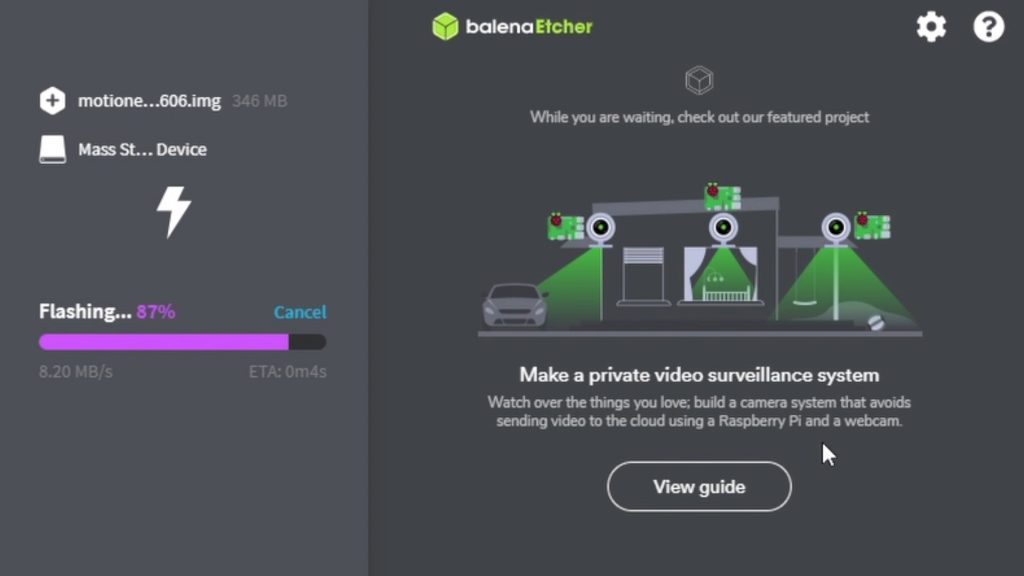

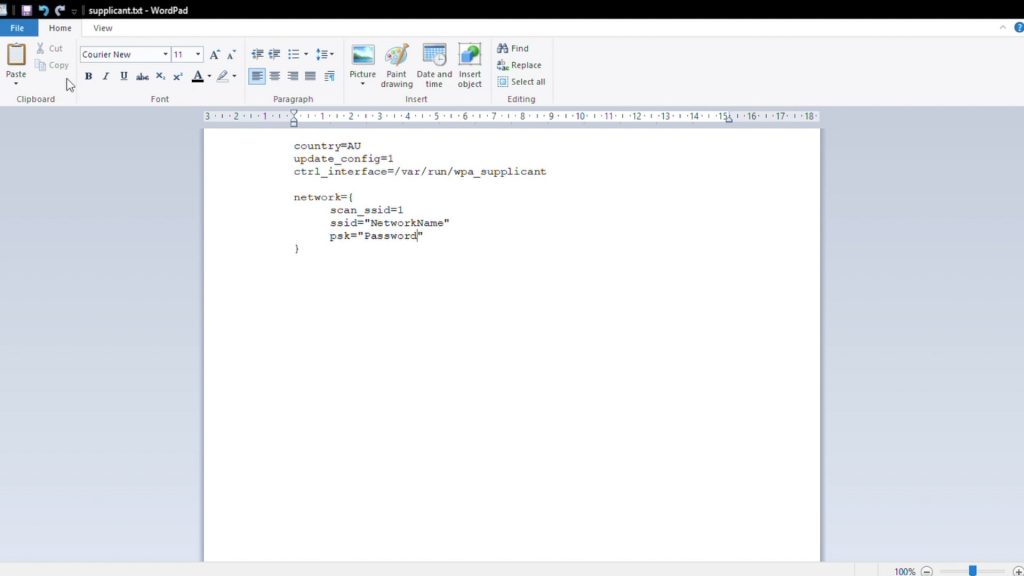

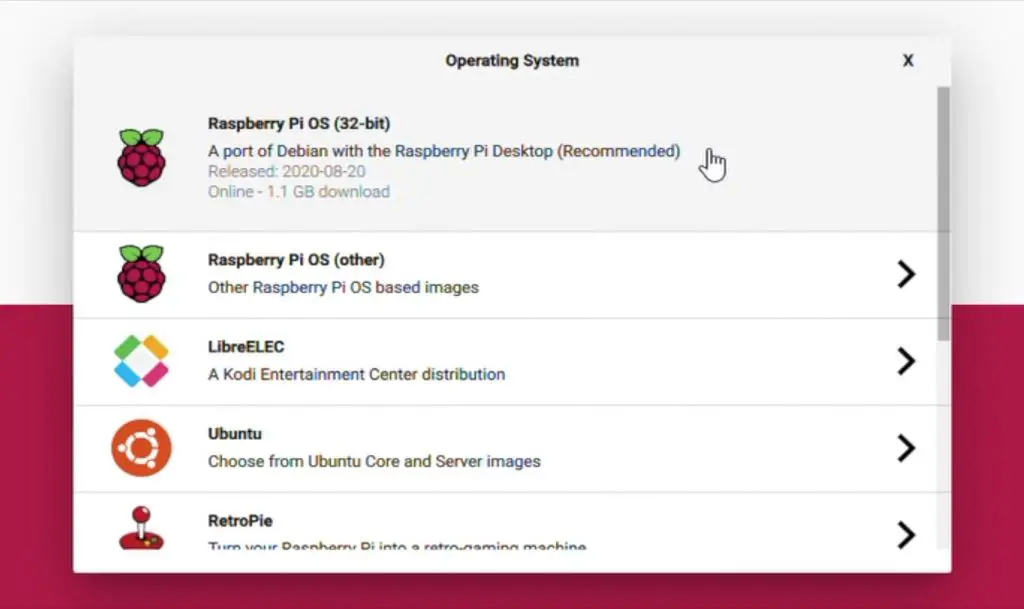

You’ll need to prepare your SD card with an installation of Raspberry Pi OS, which can now be easily done using the Raspberry Pi utility for Windows and Mac computers. You just choose the operating system you’d like, then the target SD card, and the utility does the rest for you.

For this project, you can use the full version of Raspberry Pi OS or the Lite version which doesn’t have the GUI (graphical user interface) if you’re comfortable using the terminal (command line prompts) to set it up. If you’re planning on setting it up using SSH then you’re better off just using the Lite version.

Plug your formatted SD card into your Pi and then plug the hat onto the GPIO pins.

You can now get started testing the display. I’d suggest that you get it working like this before building it into the frame if this is your first project using one of these e-ink displays.

The Waveshare Wiki for the 7.5″HD e-Paper Hat (B) is a great place to start. It walks you through the exact steps required to get the example code working and the display running through some example images and text. The Python script used for this project is based on this Waveshare example script.

If you’re not comfortable tinkering with the display and working through this Wiki then just follow the steps I’ve outlined in the subsequent sections to get it working for this specific project.

Build The Electronics Into The Frame Or Display Box

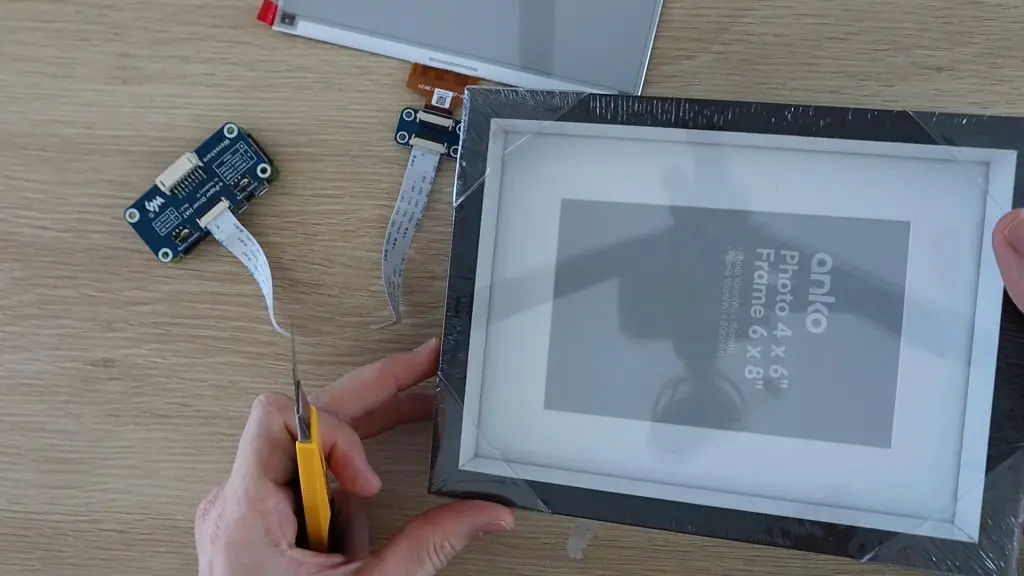

Now let’s build the display into the frame or display box. I found this cheap 6×8 inch box frame which will work quite well. You should be able to pick up a shadow box or deep photo frame around this size from a local discount store for a few dollars.

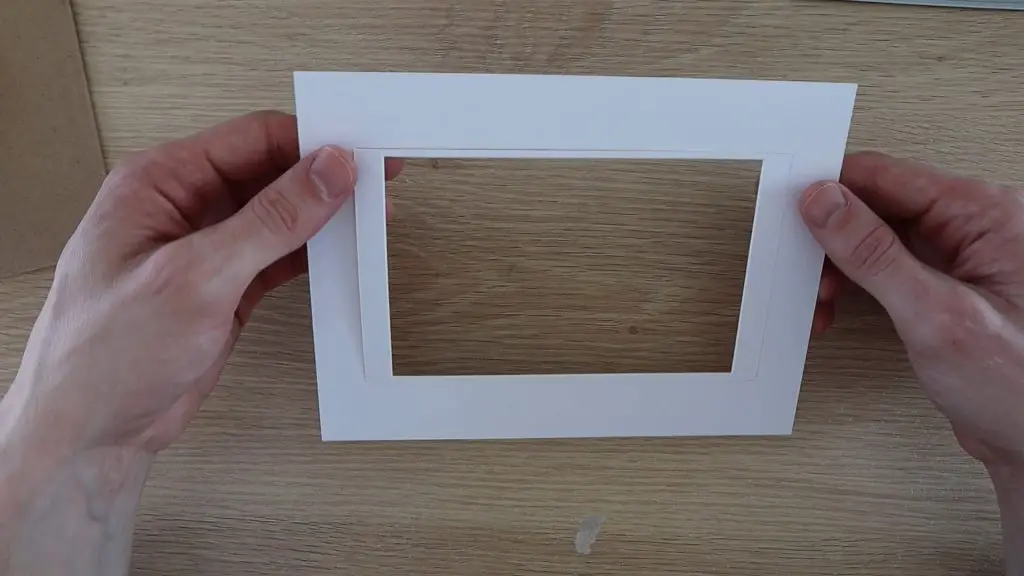

I started by removing the back layer to get to the white frame panel.

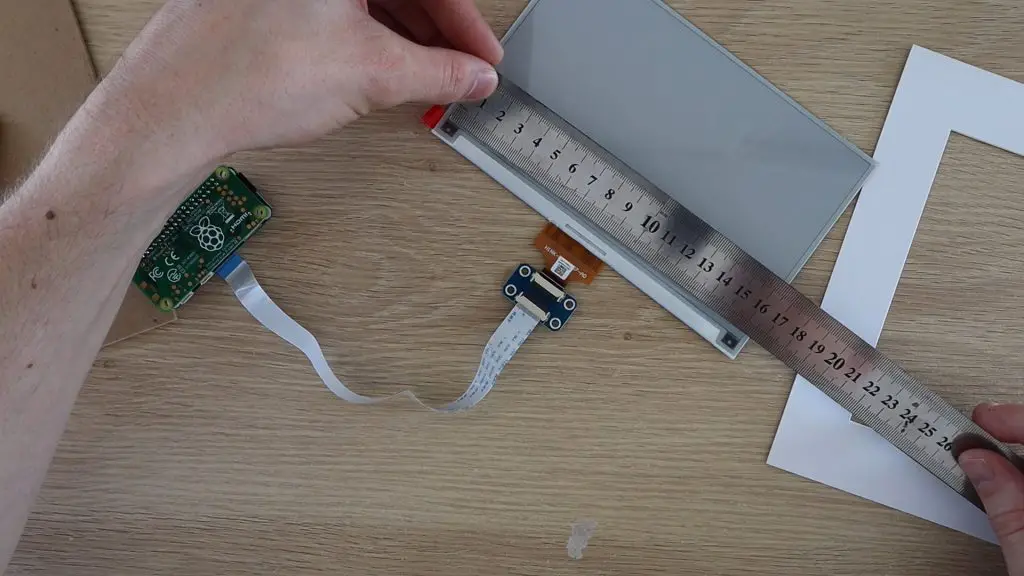

This is likely sized for a 4×6 inch photo like mine, so you’ll need to open it up a bit using a craft knife and a ruler so that it fits your display.

Measure the size of the display area and then mark it out on your frame insert.

Use a sharp craft knife and a ruler to cut along the new lines to open the frame up to fit the display.

You could also just adjust the display content size to fit within the frame area if you don’t want to modify yours.

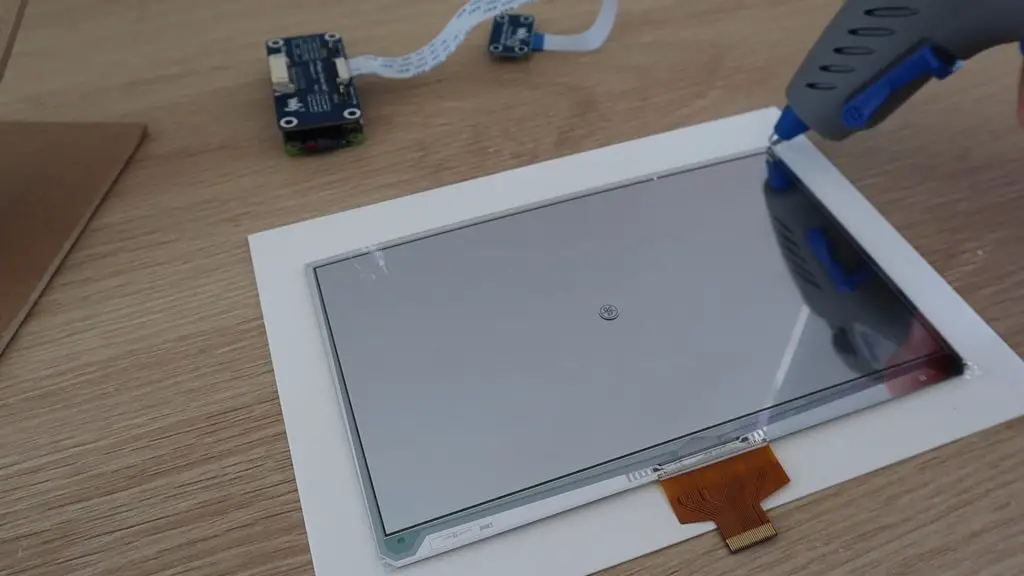

Peel off the protective film from the display.

Then carefully glue the back of the display to the frame, making sure that it’s centred and straight. I used a drop of hot glue on the corners to hold it in place.

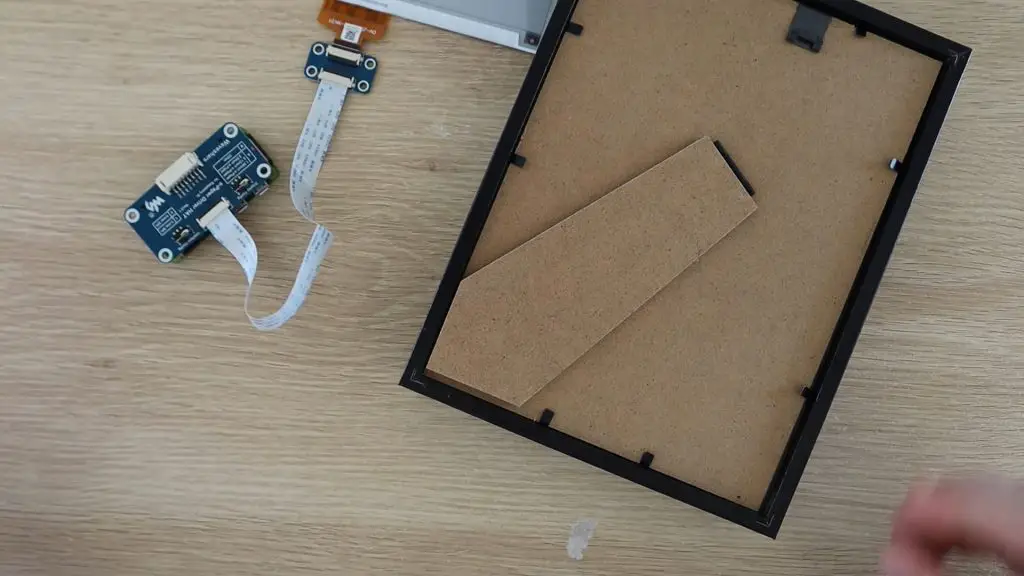

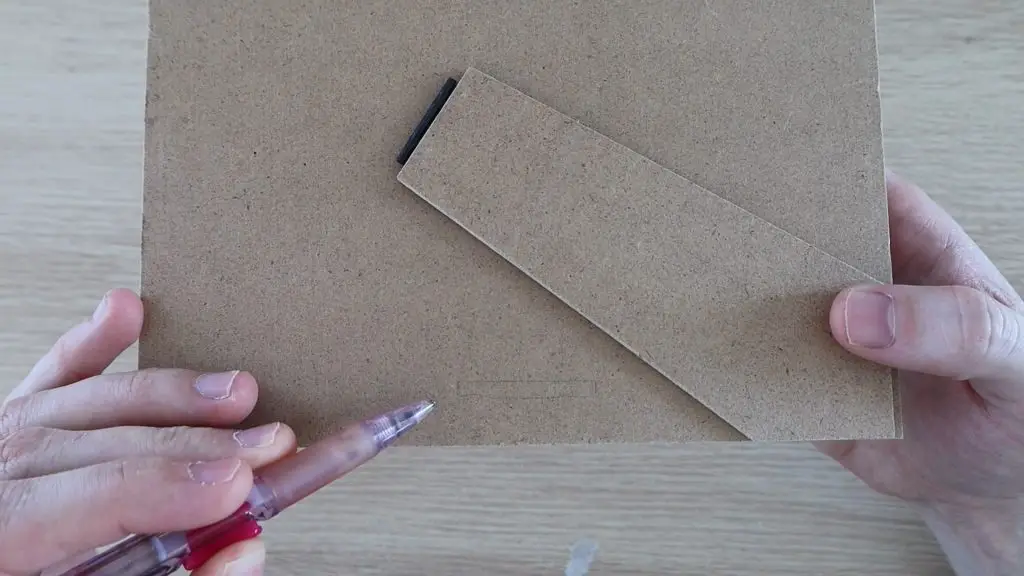

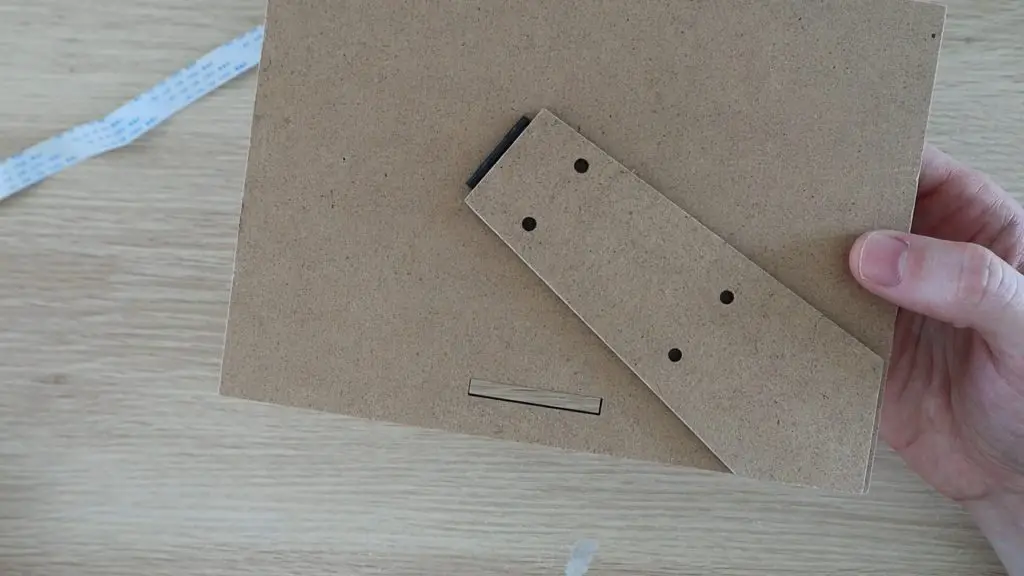

Next, mark out and cut a slot in the back layer to pull the display’s ribbon cable through.

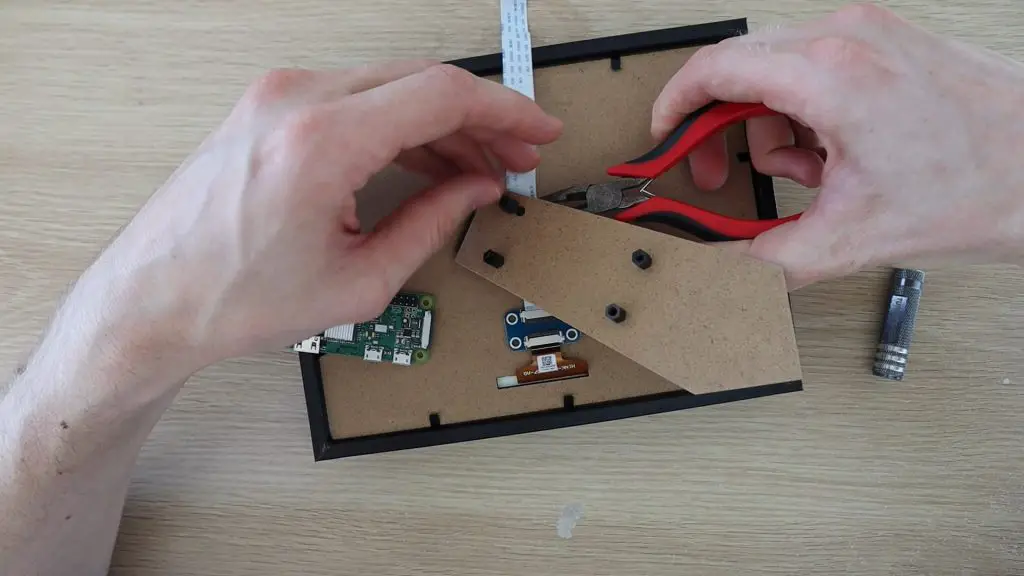

I also made the holes to mount the Raspberry Pi onto the stand.

Now re-assemble the frame and clamp the back layer back into place. If you don’t want a glossy finish to your frame, you could remove the glass panel from the front or use a matt finish panel instead.

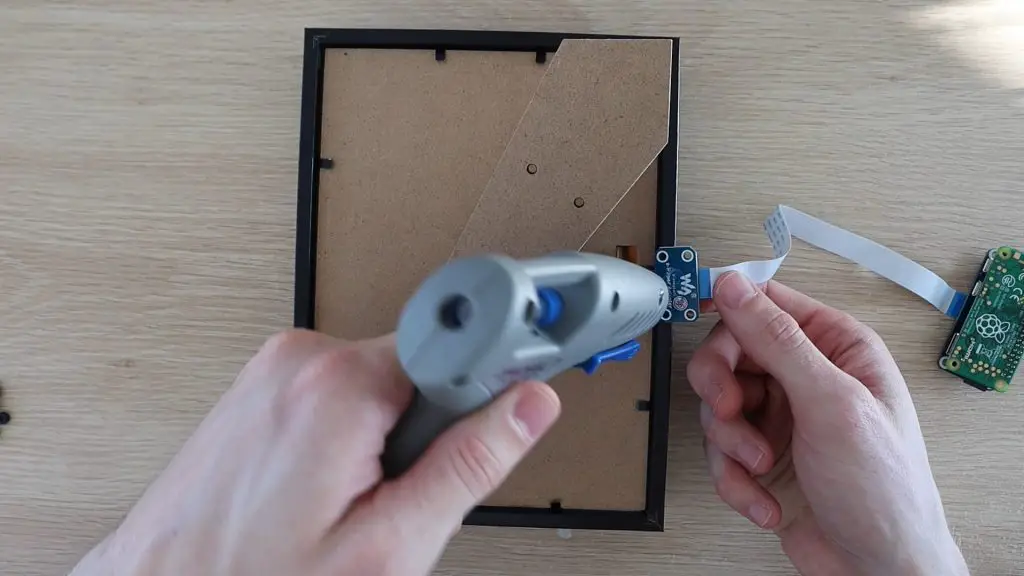

Plug the display back into the controller and glue the connector in place so that it doesn’t put any stress onto the display’s ribbon cable.

Now lets add some plastic standoff mounts to mount the Raspberry Pi and the Hat.

Your frame is now complete and ready for programming.

Setting Up & Programming Your Raspberry Pi Zero W

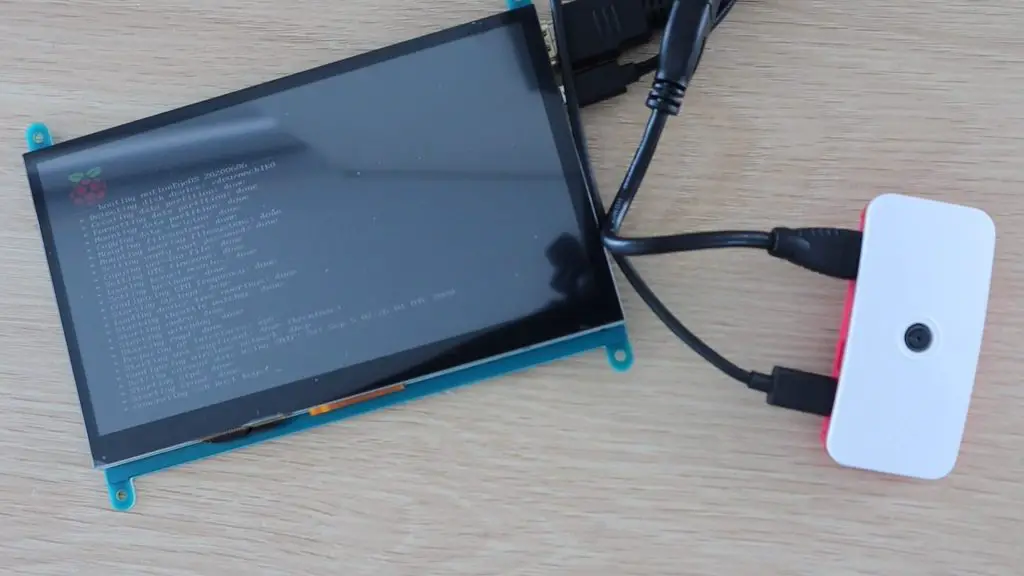

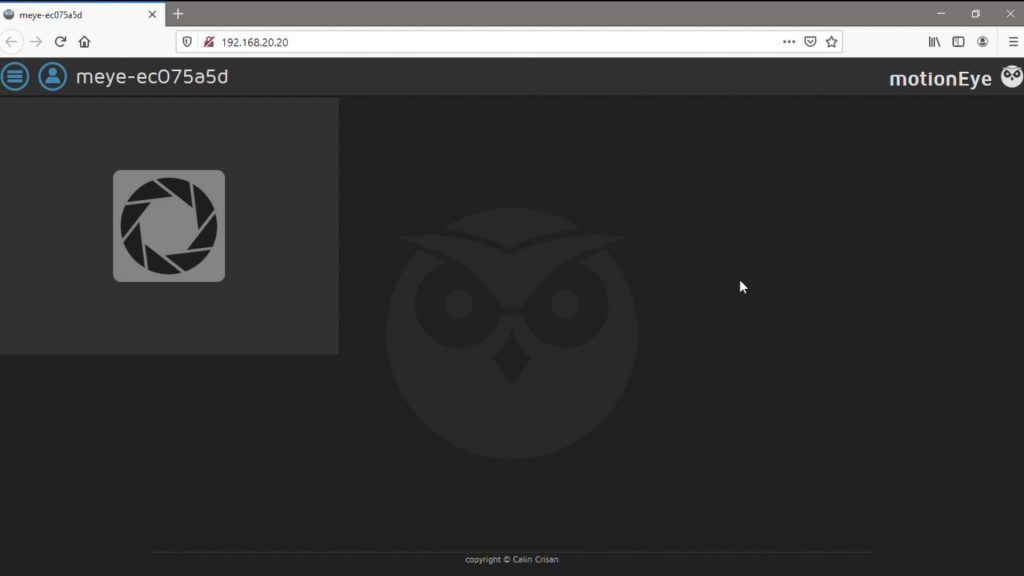

The first time you boot up the pi, it will take a while to set up the Operating System, get connected to your WiFi network, and do any updates. Most of this is done automatically and you should be guided through prompts until you get to your Desktop view and your Pi is ready for programming.

Before you start with the Python script, there are a couple of libraries to install and setup steps to work through.

Please also remember that software changes quite often with these devices, these steps work as of 6 October 2020, but you may encounter errors in the future as packages are updated and pieces of software become obsolete.

Setup & Library Installation

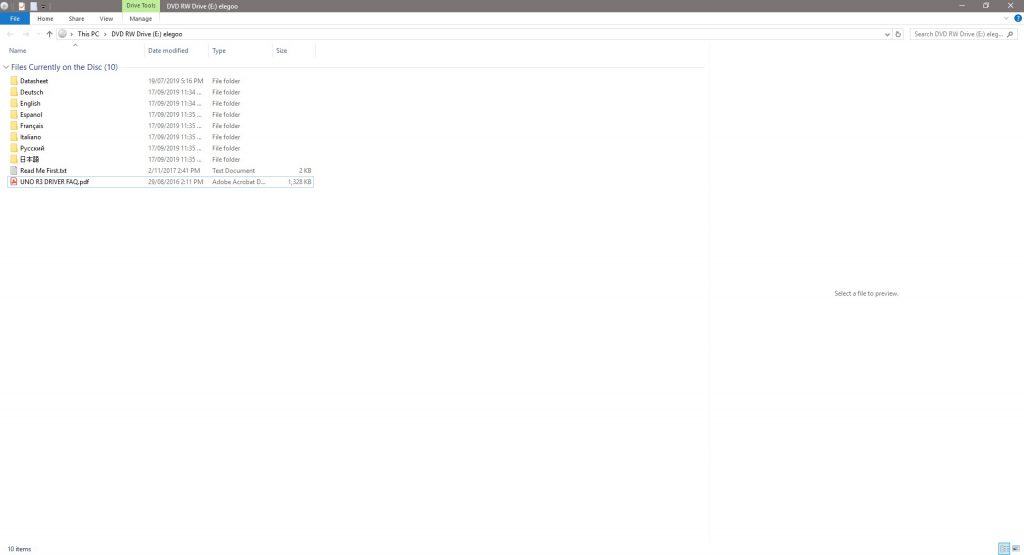

These initial setup steps are as per the display’s wiki from the Waveshare Wiki for the 7.5″HD e-Paper Hat (B)

Enable The SPI Interface

The Raspberry Pi communicates to the display controller using the SPI interface, so you’ll need to enable it on your Pi.

Open the terminal window and enter the following command:

sudo raspi-configChoose Interfacing Options -> SPI -> Yes

You may need to reboot your Pi for the changes to take effect.

sudo rebootOnce you’ve restarted your Pi, open a new terminal window again and enter the following to install the libraries:

Install the BCM2835 libraries:

wget http://www.airspayce.com/mikem/bcm2835/bcm2835-1.60.tar.gz

tar zxvf bcm2835-1.60.tar.gz

cd bcm2835-1.60/

sudo ./configure

sudo make

sudo make check

sudo make installInstall the WiringPi libraries:

sudo apt-get install wiringpi

wget https://project-downloads.drogon.net/wiringpi-latest.deb

sudo dpkg -i wiringpi-latest.deb

gpio -vInstall the Python2 libraries:

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install python-pip

sudo apt-get install python-pil

sudo apt-get install python-numpy

sudo pip install RPi.GPIO

sudo pip install spidevInstall the Python3 libraries:

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install python3-pip

sudo apt-get install python3-pil

sudo apt-get install python3-numpy

sudo pip3 install RPi.GPIO

sudo pip3 install spidevGet Your YouTube API Key

In order for the Python script to retrieve your current subscriber count and number of views, you’ll need to add your Channel ID and your YouTube API key.

Here’s how to generate your API key:

Go to the Google API web page while signed in to your google account associated with your YouTube channel – https://console.developers.google.com

Go to your Dashboard and the click on “Create Project”, choose a name for your project and click “Create”.

Next, click on “Enable APIs and Services” and type – Youtube Data API v3 – into the search box. Enable it and click “Create Credentials”.

On the next page, you should see a link to create an API key in small letters, click on this link.

Next click “API Restrictions” and select “YouTube Data API v3”.

Click “Create” and you should then be given your API key which you’ll need to copy into the main Python script below.

You’ll also need to get your Channel ID. You can find this under “Advanced Settings” for your channel account. Click on your profile picture in the top right, then go to “Settings”, wait for the page to load and then click on “Advanced Settings” from the menu on the left.

You can test your API Key and Channel ID by going to the following address in your broswer, replacing YourChannelID and YourAPIKey with the ones you’ve just got:

https://www.googleapis.com/youtube/v3/channels?part=statistics&id=YourChannelID&key=YourAPIKey

Load The Python Script

This script is largely based on the Waveshare example script, with a couple of additions and changes to get the information from Youtube:

#!/usr/bin/python

# -*- coding:utf-8 -*-

import sys

import os

import requests

picdir = os.path.join(os.path.dirname(os.path.dirname(os.path.realpath(__file__))), 'pic')

libdir = os.path.join(os.path.dirname(os.path.dirname(os.path.realpath(__file__))), 'lib')

if os.path.exists(libdir):

sys.path.append(libdir)

import logging

from waveshare_epd import epd7in5b_HD

import time

from PIL import Image,ImageDraw,ImageFont

import traceback

from datetime import date

today = str(date.today())

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.DEBUG)

# Set up the structure of the API request URL

URL = "https://www.googleapis.com/youtube/v3/channels"

type = "statistics"

channelid = "******"

apikey = "******"

PARAMS = {('part', type), ('id',channelid), ('key',apikey)}

#Get API results

r = requests.get(url = URL, params = PARAMS)

data = r.json()

subscribers = int(data['items'][0]['statistics']['subscriberCount'])

totalviews = int(data['items'][0]['statistics']['viewCount'])

#Convert results to a string and format numbers with commas

noViews = 'Views: ' + f"{totalviews:,d}"

noSubs = 'Subscribers: ' + f"{subscribers:,d}"

#Update the display

try:

logging.info("Updating display")

epd = epd7in5b_HD.EPD()

logging.info("initialising and clearing display")

epd.init()

epd.Clear()

font12 = ImageFont.truetype(os.path.join(picdir, 'Font.ttc'), 12)

font24 = ImageFont.truetype(os.path.join(picdir, 'Font.ttc'), 24)

font32 = ImageFont.truetype(os.path.join(picdir, 'Font.ttc'), 32)

logging.info("Drawing new image")

blackImage = Image.new('1', (epd.width, epd.height), 255)

redImage = Image.new('1', (epd.width, epd.height), 255)

draw_blackImage = ImageDraw.Draw(blackImage)

draw_redImage = ImageDraw.Draw(redImage)

draw_blackImage.text((312, 360), 'Michael Klements', font = font32, fill = 0)

draw_blackImage.text((200, 435), noViews, font = font24, fill = 0)

draw_blackImage.text((475, 435), noSubs, font = font24, fill = 0)

draw_blackImage.text((800, 500), today, font = font12, fill = 0)

bmp = Image.open(os.path.join(picdir, 'youtubeIcon.bmp'))

redImage.paste(bmp, (265,80))

epd.display(epd.getbuffer(blackImage),epd.getbuffer(redImage))

#To delay before clearing, if used

#time.sleep(20)

#To clear the display afterwards

#logging.info("Clear...")

#epd.init()

#epd.Clear()

logging.info("Putting display to sleep")

epd.sleep()

epd.Dev_exit()

except IOError as e:

logging.info(e)

except KeyboardInterrupt:

logging.info("ctrl + c:")

epd7in5b_HD.epdconfig.module_exit()

exit()

Copy the root folder into your home/pi/ directory so that your script is in /home/pi/SubCount/SubCount/subCount.py

You may also need to include the Font used from the Waveshare example, paste this font into the pic folder along with youtubeIcon.bmp

We start by importing the libraries, functions and directories needed as well as getting the current date.

We then use the Youtube API to get the subscriber count and number of views. Remember to update these in your script before running it, just replace the ****** with your own ID and Key.

We then format the returned numbers with commas and finally connect to the display to update it. You’ll also need to update your channel name to your own channel name by replacing the “Michael Klements” with your own channel name in this portion of the code.

The script then puts the display into a low power sleep again until the next update.

If you’d like to play around with the layout of the display, try adjusting the numbers in the display portion.

draw_blackImage.text((200, 435), noViews, font = font24, fill = 0)

The first number is the X position and the second number is the Y position of each object to be displayed.

You’ll also need to run the setup.py script, included with the above code download, once before you run the actual script:

import sys

from setuptools import setup

setup(

name='waveshare-epd',

description='Waveshare e-Paper Display',

author='Waveshare',

package_dir={'': 'lib'},

packages=['waveshare_epd'],

)

Try to run the script and after a few seconds, you should see your display start to refresh. The full refresh of the display does take quite a while, somewhere around 30 seconds on the Raspberry Pi Zero. It is a bit faster on a Raspberry Pi 4.

The flickering is normal for these controllers and is done to prevent burn-in on the display. It’ll first flicker black and white to clear the display, then load a black and white version of the image and finally replace some of the black with red as instructed.

Schedule The Python Script To Run Automatically

Once you’ve got the script working, you’ll just need to schedule the script to run automatically using crontab, mine updates the YouTube subscriber counter display every 8 hours, running three times a day. You could probably just refresh the display once a day, but Waveshare recommends updating the display at least once every 24 hours to prevent burn-in. So I just went with every 8 hours to be safe.

I followed this guide by scottkildall to get crontab to automatically run the script at 6AM, 2PM and 10PM.

You essentially need to create a launcher.sh script in the same folder as your Python script:

#!/bin/sh

# launcher.sh

# navigate to home, then script directory, then execute, then back home

cd /

cd home/pi/SubCount/SubCount/

sudo python3 subCount.py

cd /

This script tells the Raspberry Pi to change directory to the home directory, then navigate to your script, then run the script using python3 and then go back to the home directory.

Once you’ve got your launcher script created, open crontab by opening a terminal window and entering:

crontab -eYou’ll then edit crontab to run the launcher.sh script by adding lines:

0 22 * * * /home/pi/SubCount/SubCount/launcher.sh

0 6 * * * /home/pi/SubCount/SubCount/launcher.sh

0 14 * * * /home/pi/SubCount/SubCount/launcher.shSave the changes and your Raspberry Pi should now be all set to update automatically at 06:00, 14:00 and 22:00. You can edit the minutes and hours in the above lines to set the times you’d prefer. The first is the minutes and the second the hours, in 24 hour format.

Using Your YouTube Subscriber Counter

Once you’ve got the scripts set up and scheduled to run automatically, your Youtube Subscriber Counter is complete. Just plug it into a USB power supply and place it on your desk or shelf.

The date in the bottom right corner is updated to reflect the last time the stats were updated, so you’ll be able to see if anything goes wrong and the Pi stops updating the display regularly by checking this date as well.

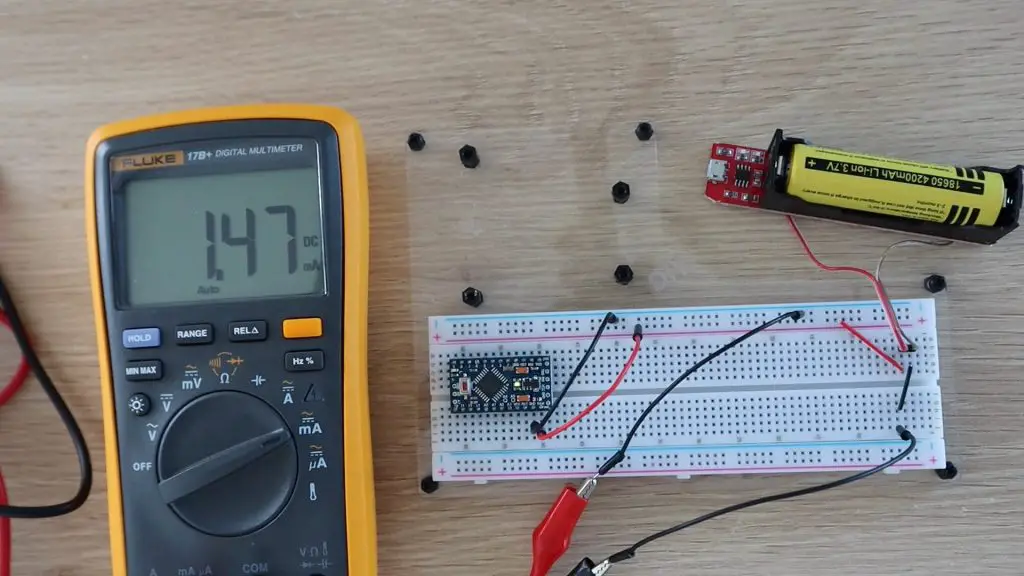

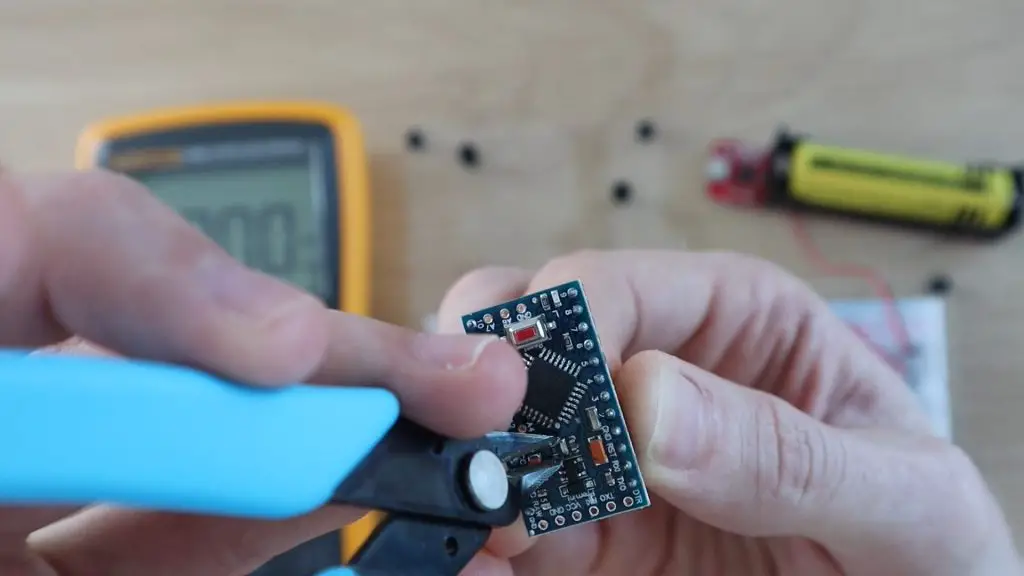

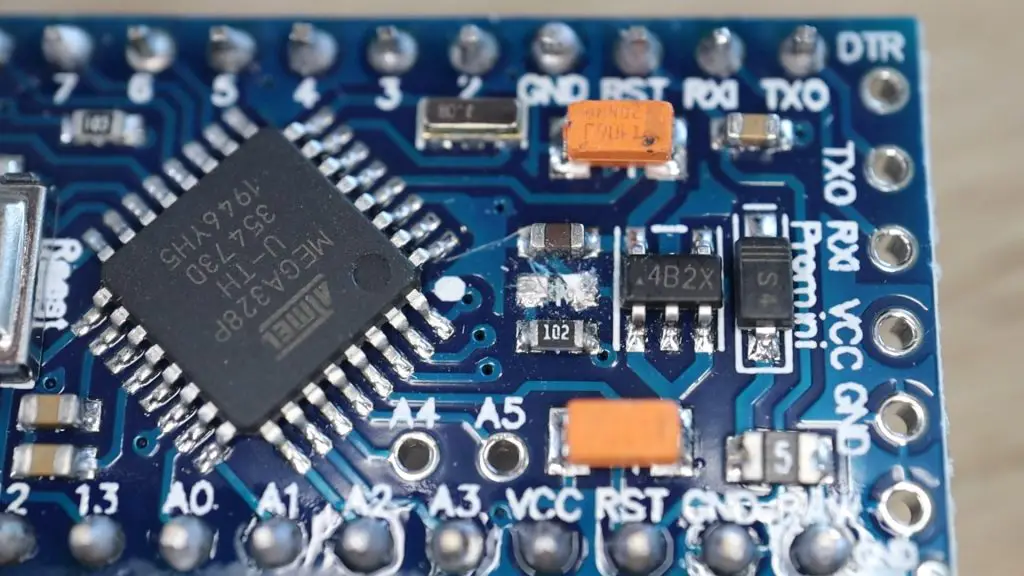

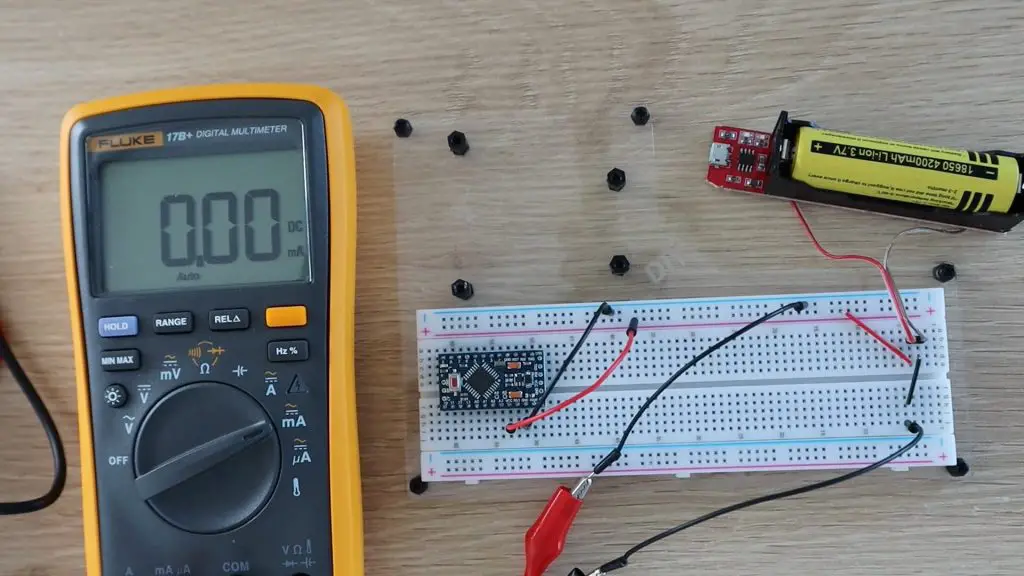

I wanted to build this particular YouTube Subscriber Counter using a Raspberry Pi Zero W, but you could also use an ESP32 to use even less power by putting the controller to sleep between updates to the display, something that’s difficult to do on a Raspberry Pi.

Let me know what you think of it in the comments section and let me know if you try building your own!

Share This Guide