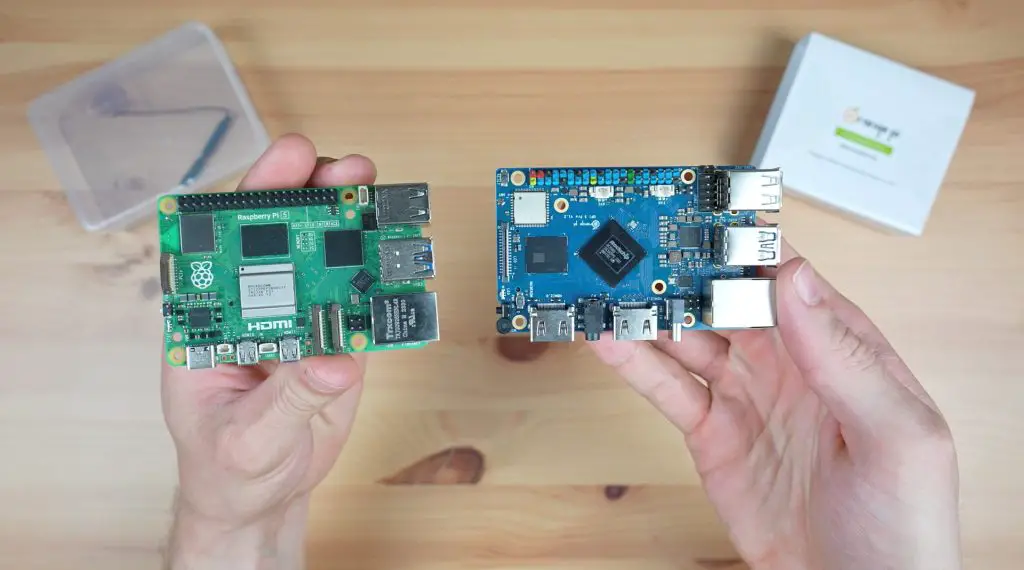

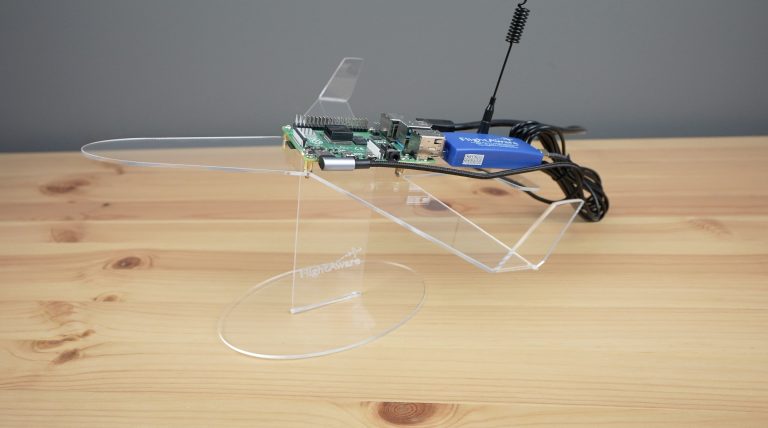

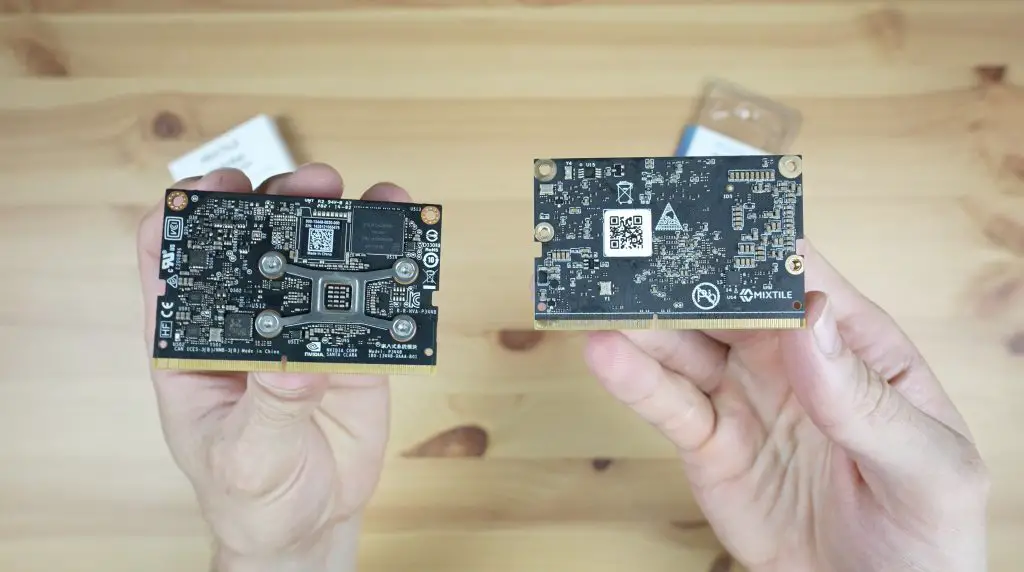

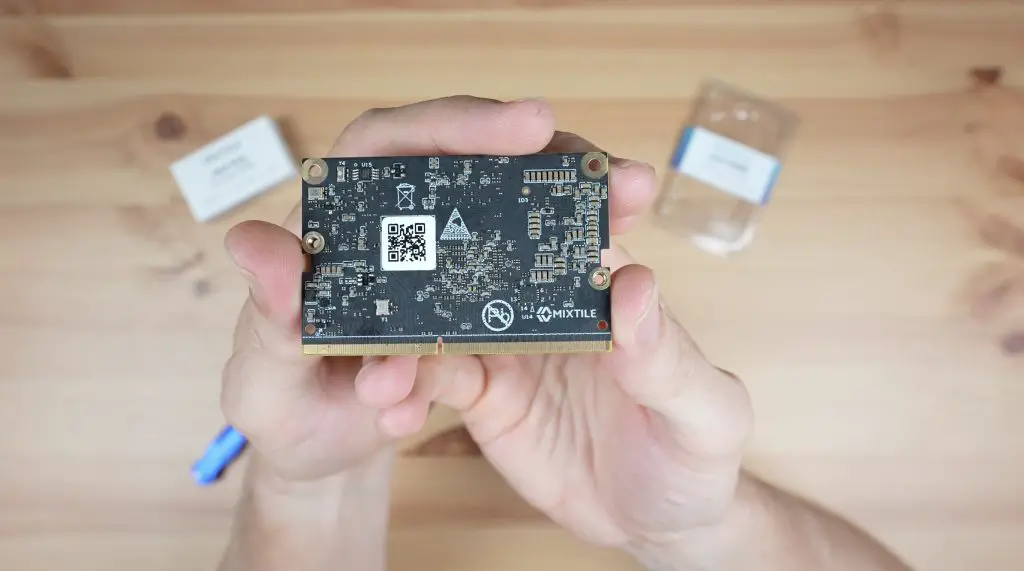

Today we’re taking a look at the Mixtile Core 3588E. This is a new system on a module, based on the Rockchip RK3588. It’s in the same 69.6 x 45mm form factor as the NVIDIA Jetson TX2 NX module and uses the same 260-pin edge connector – so is compatible with many of the same carrier boards.

Here’s my video review and testing of the Core 3588E, read on for my written review and results:

Where To Buy The Mixtile Core 3588E

Equipment Used

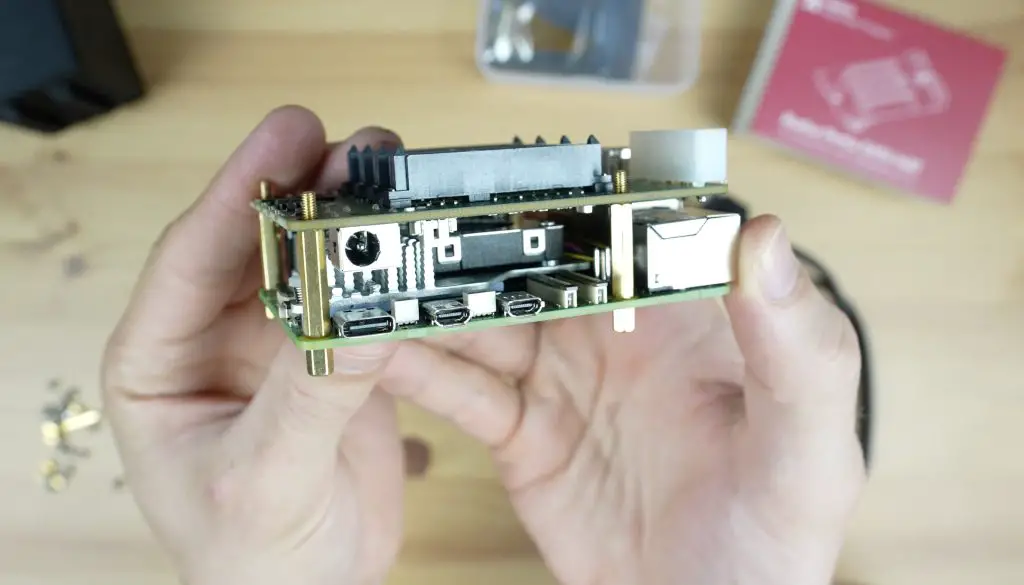

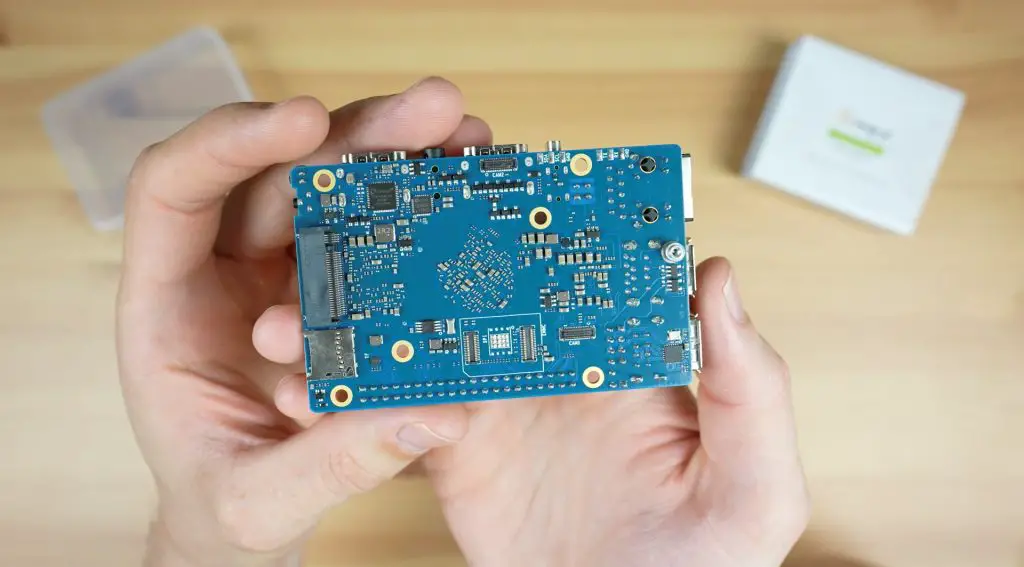

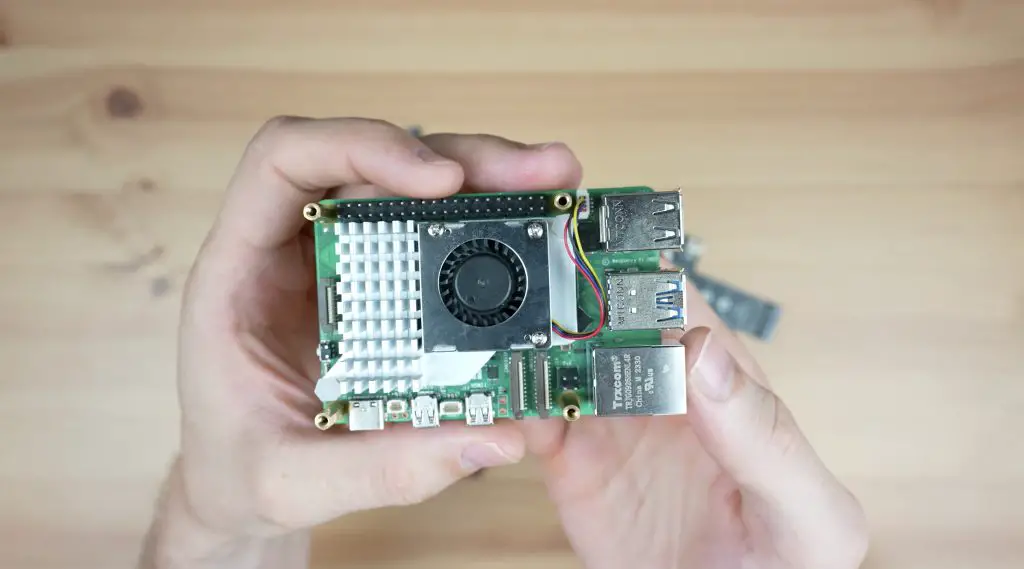

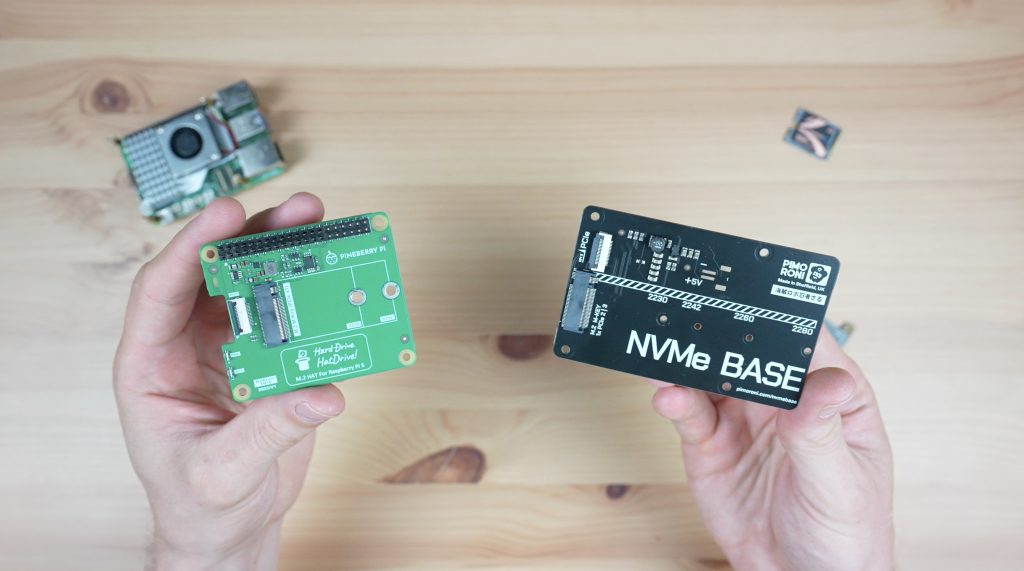

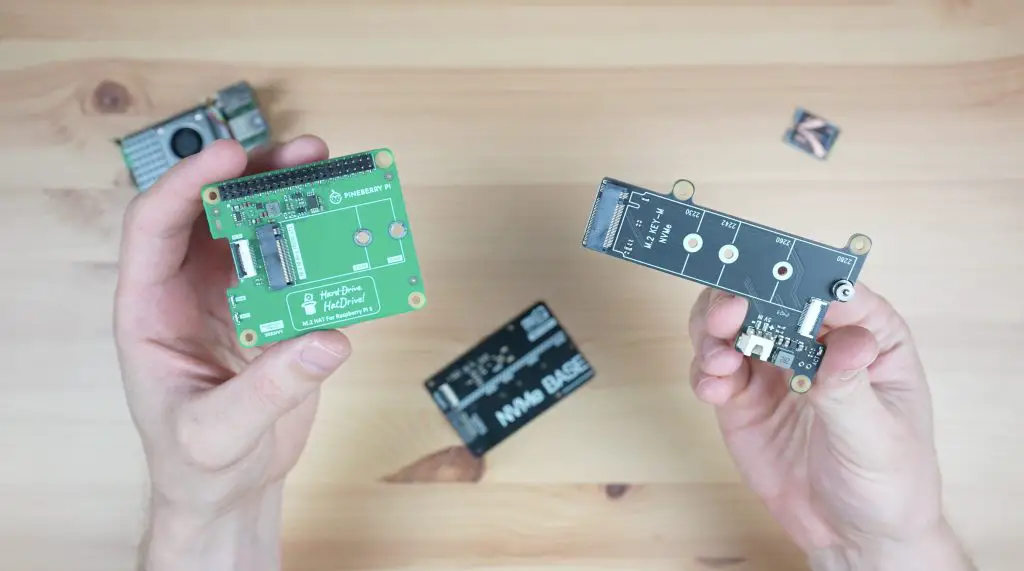

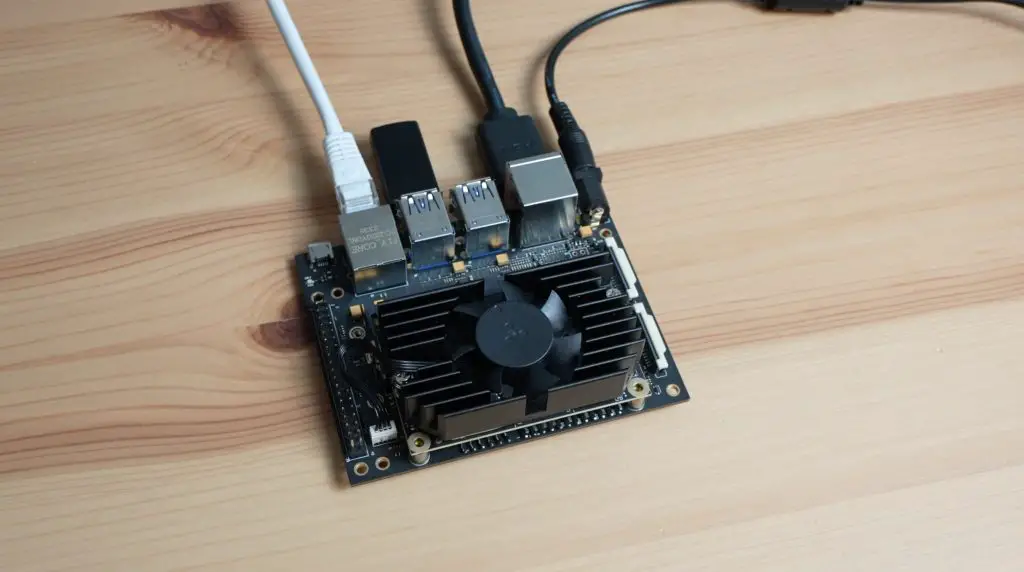

Taking A Look At The SOM & Carrier

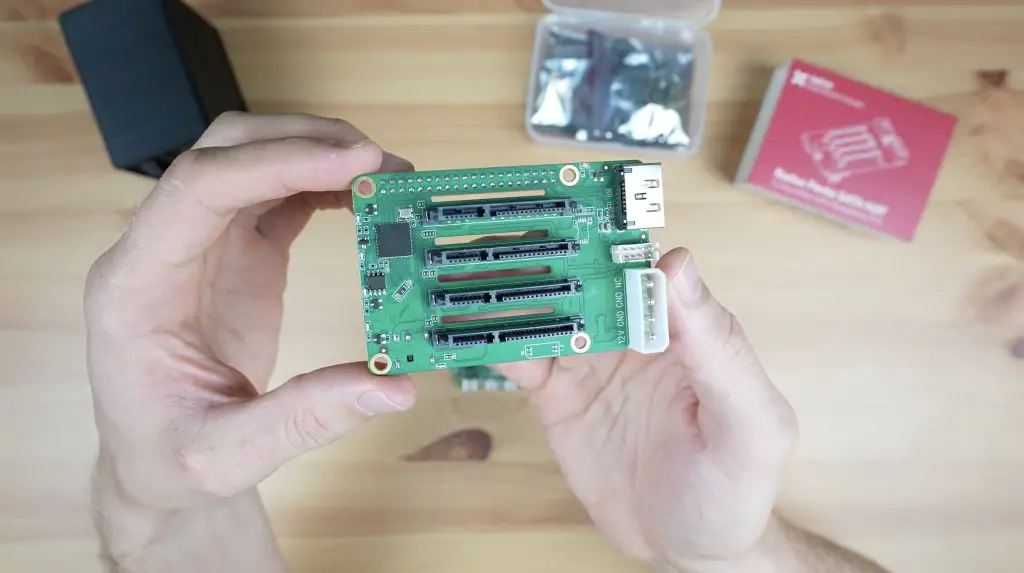

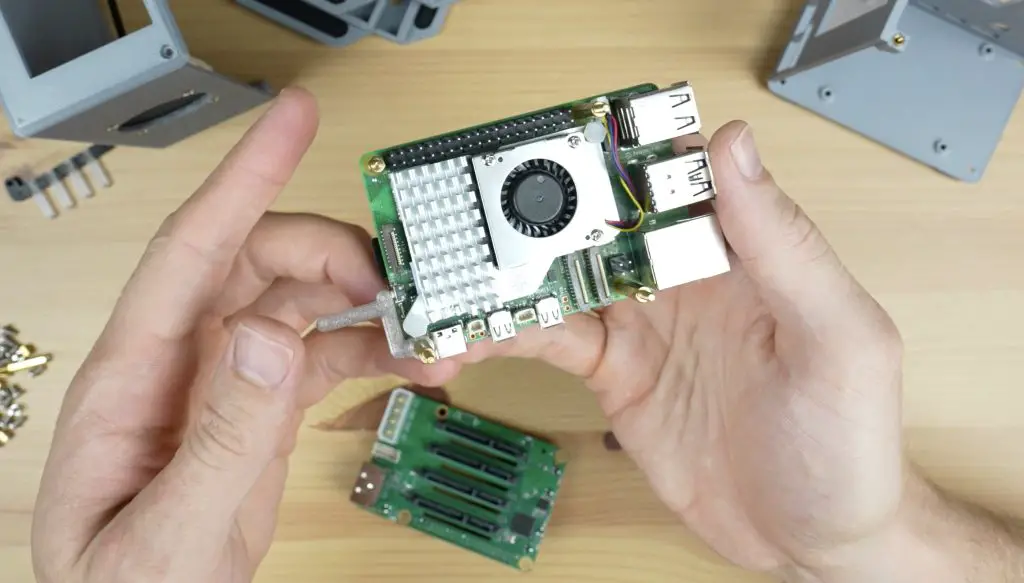

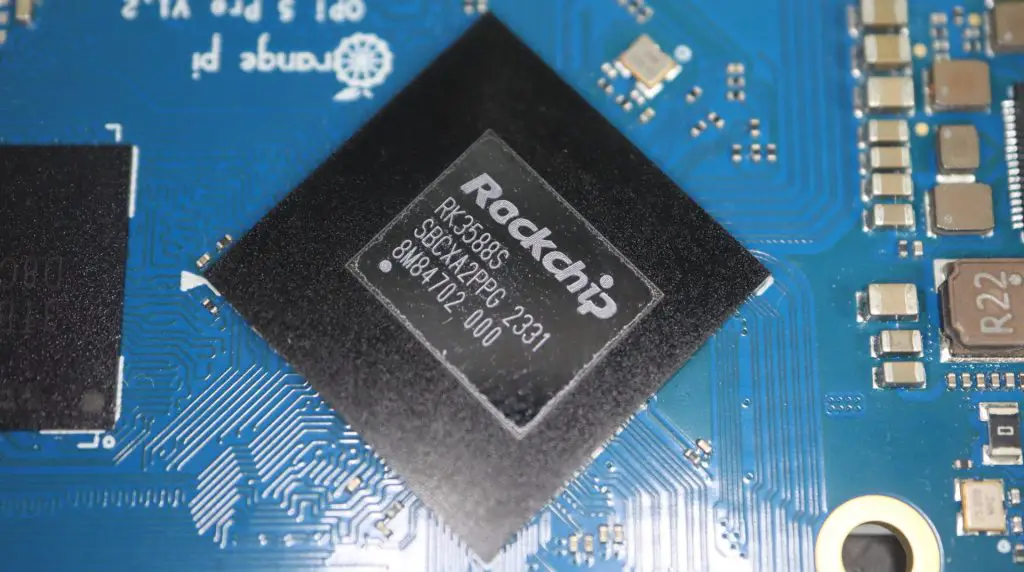

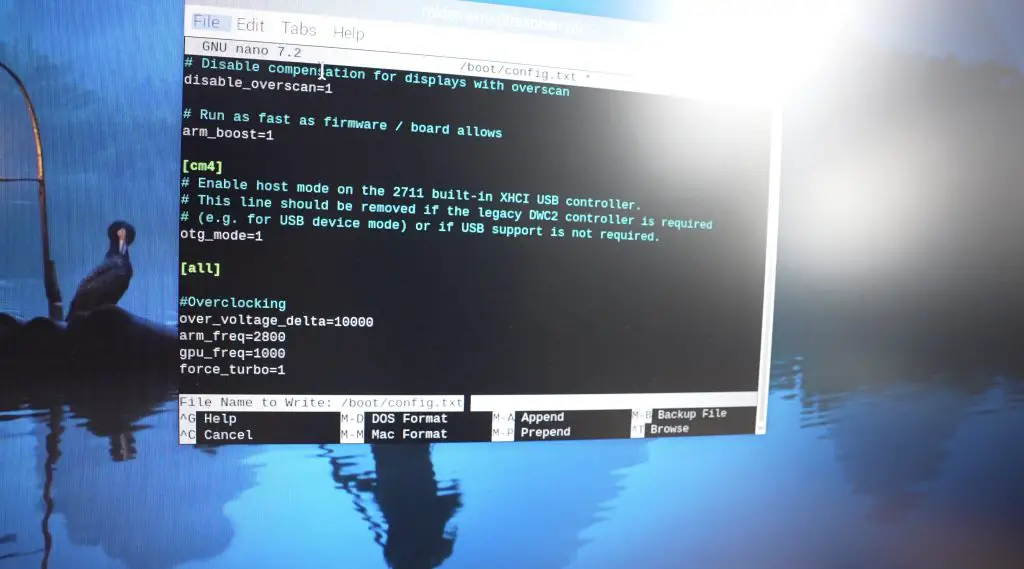

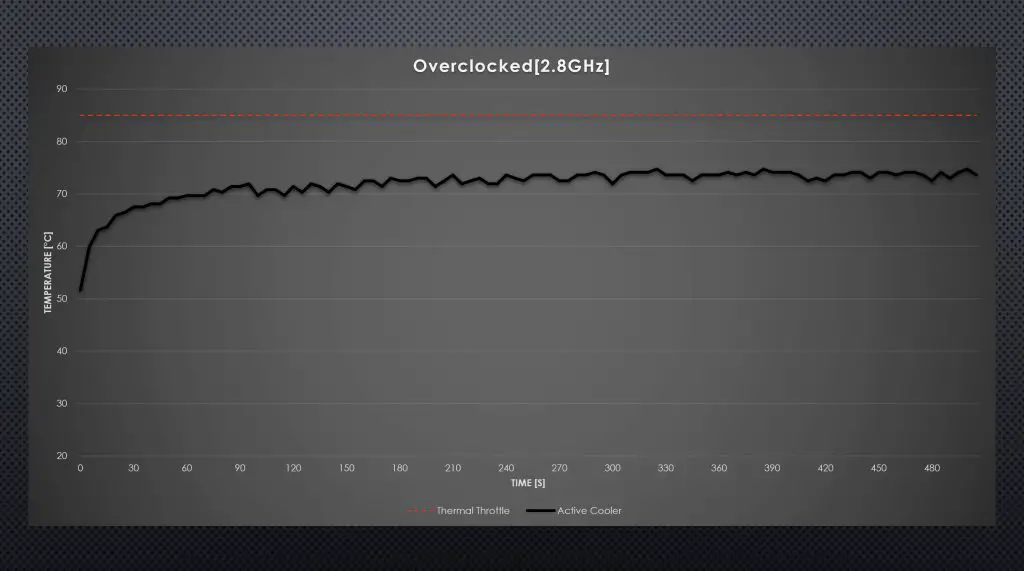

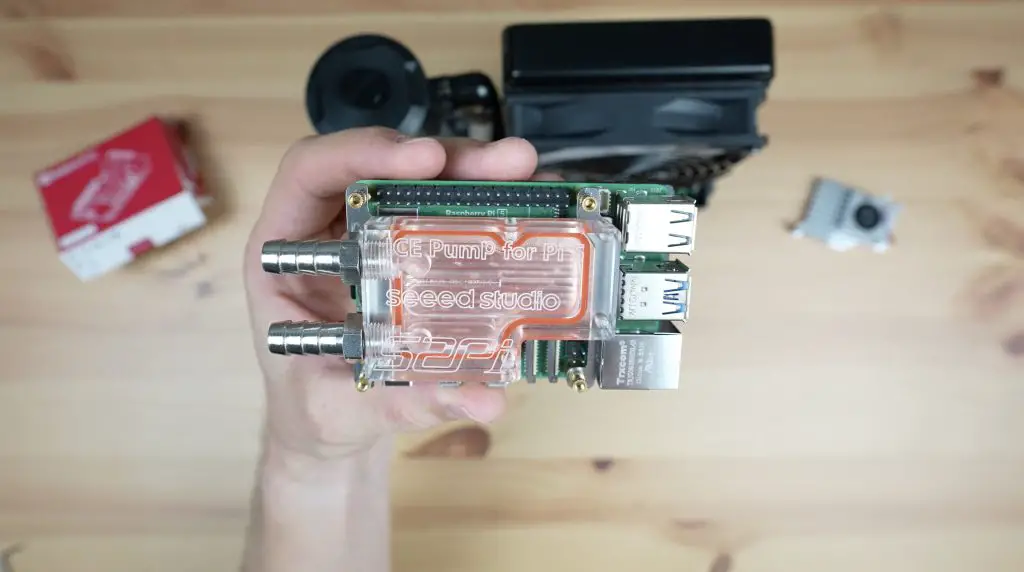

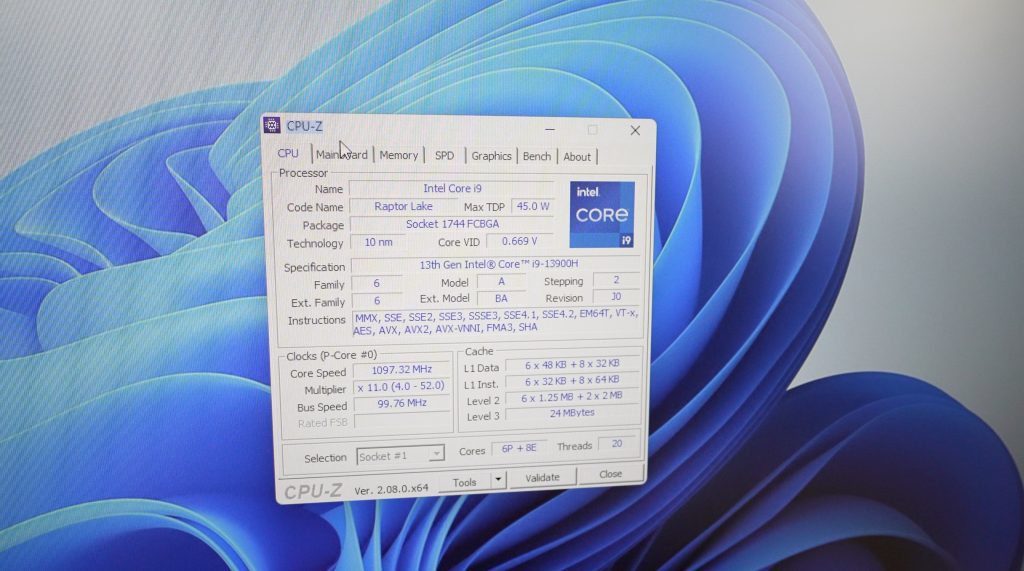

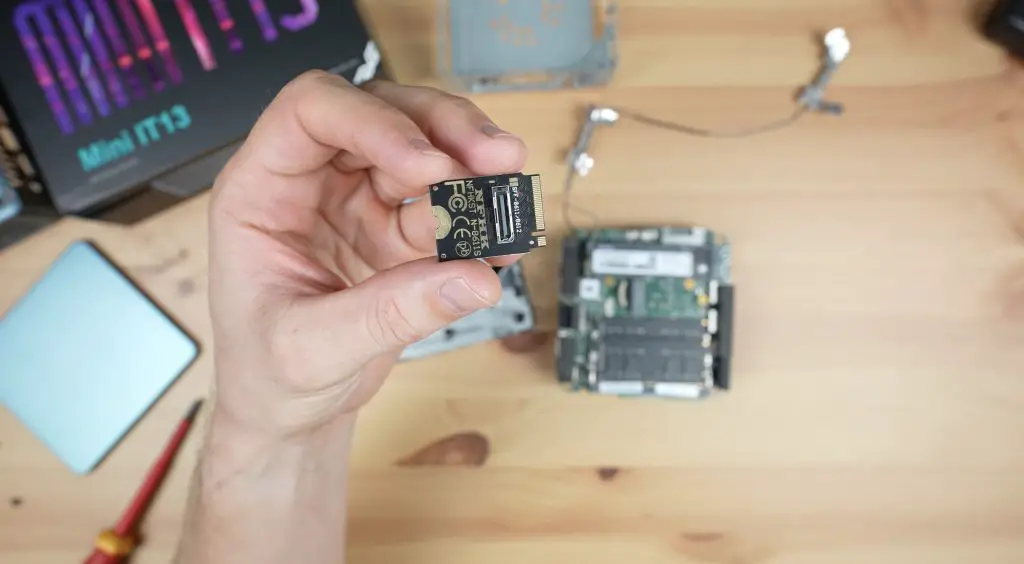

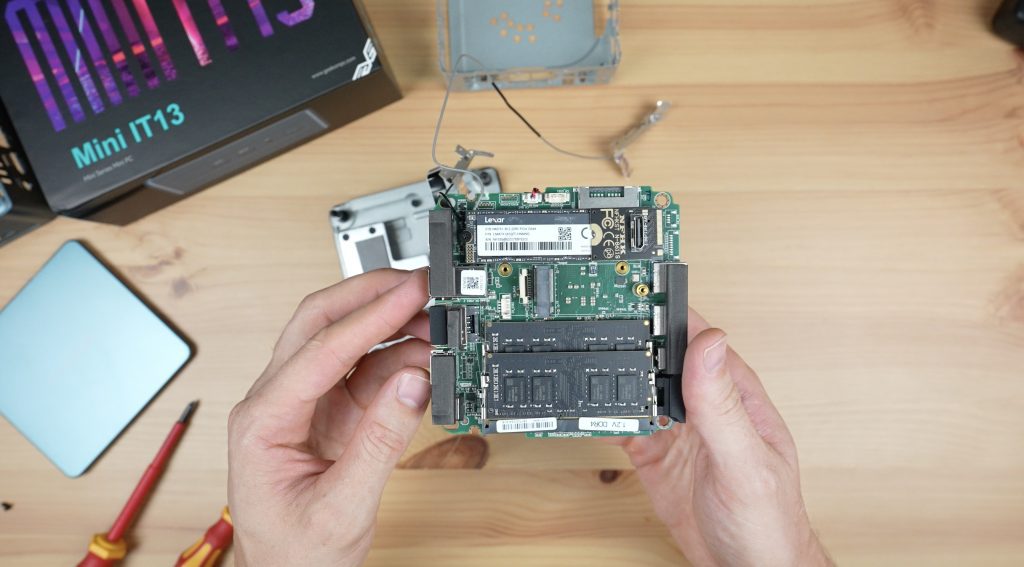

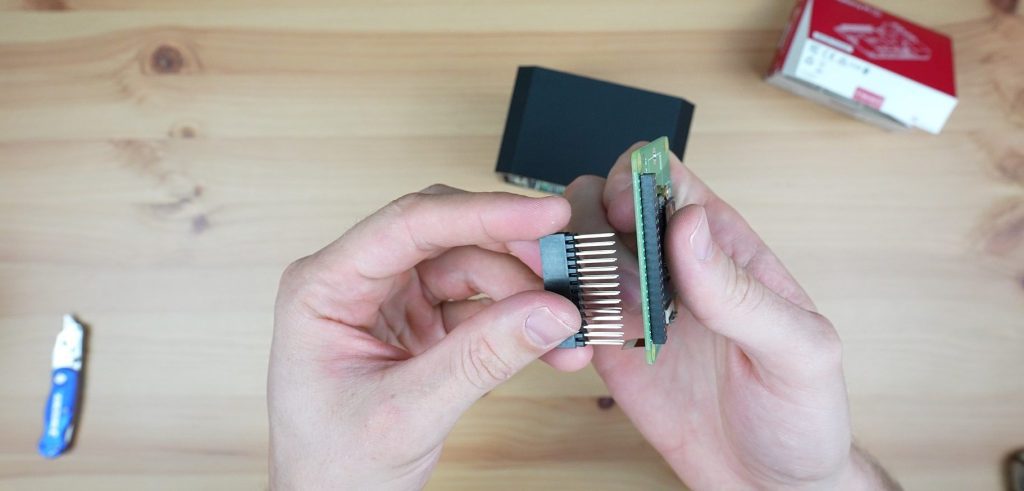

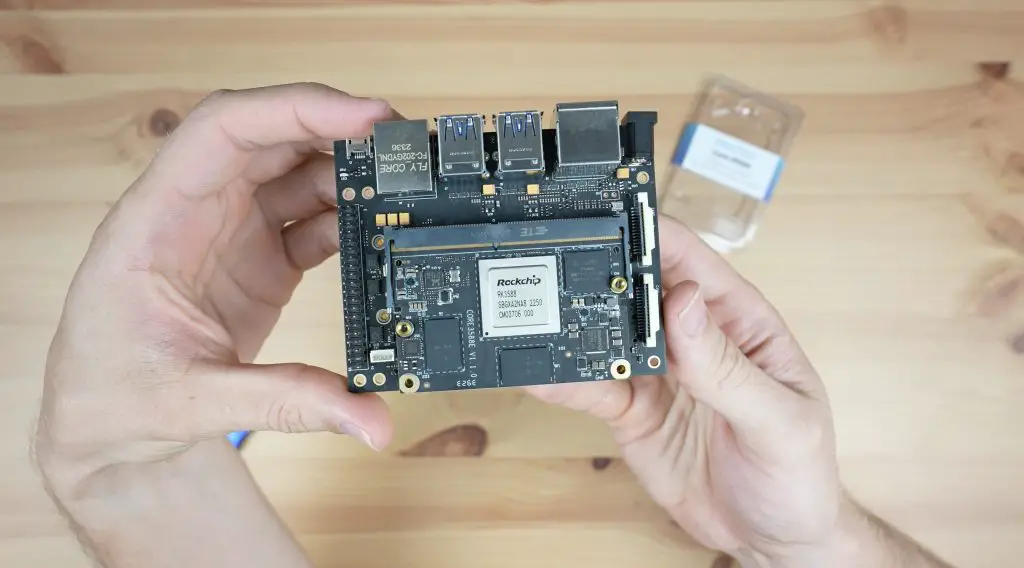

In the centre of the module, we’ve got the Rockchip RK3588 processor. This is an 8-core, 64-bit processor that consists of a 4-core Cortex A76 processor running at 2.4GHz and a 4-core Cortex A55 processor running at 1.8GHz. In addition to this, it’s got an Arm Mali G610 GPU.

Alongside it is the eMMC storage module and on the other side of the CPU are the LPDDR4 RAM chips.

The Core 3588E comes in three configurations;

- 4GB of RAM and 32GB of storage selling for $132

- 16GB of RAM and 128GB of storage selling for $190

- 32GB of RAM and 256GB of storage selling for $329

This is quite pricey for a module with this processor on it, given that you can buy a full SBC with ports broken out for this price. But they are fairly close to the pricing on the Turing RK1 modules with the same SOC, so let’s see how it performs.

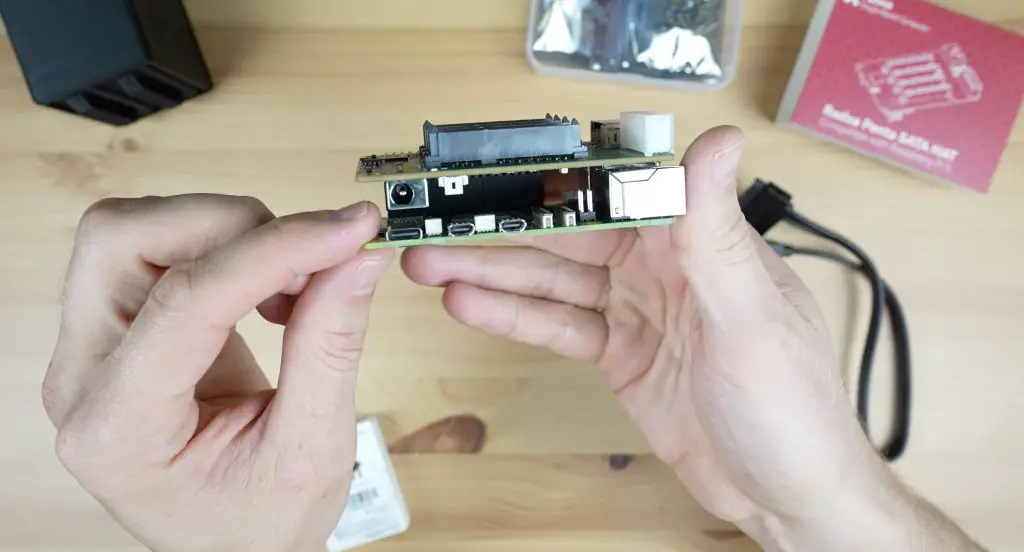

On the bottom is the 260-pin SO-DIMM connector which allows it to be plugged into devices and carrier boards.

The carrier board that you use will obviously determine which ports and interfaces are available, but the 3588E supports the following basic IO;

- HDMI and display port interfaces up to 8K60

- USB3.0

- USB2.0

- PCIe 3.0

- PCIe 2.1

- UART, SPI, I2C, CAN, I2S, PWM and

- Digital IO pins

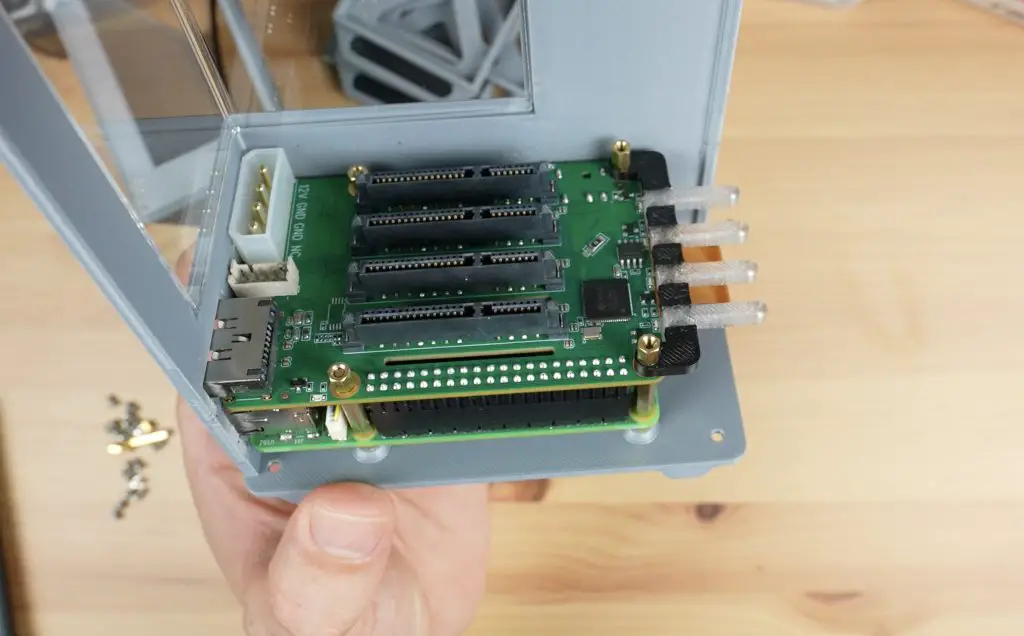

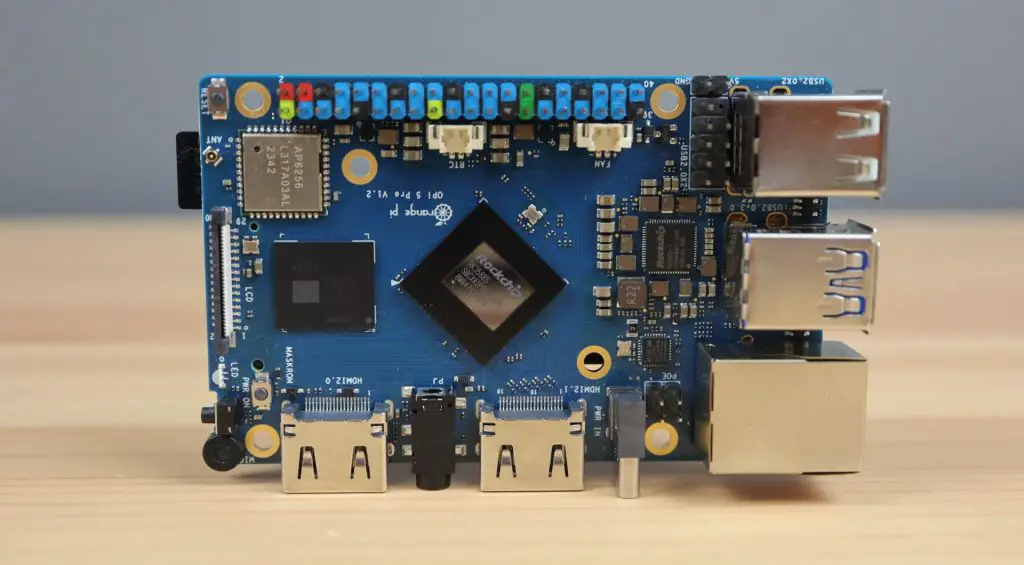

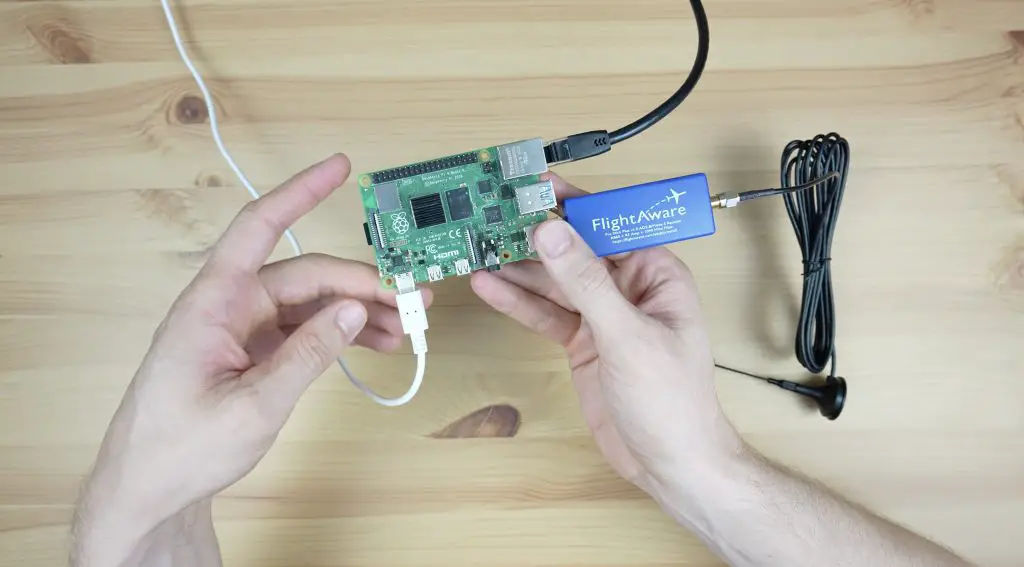

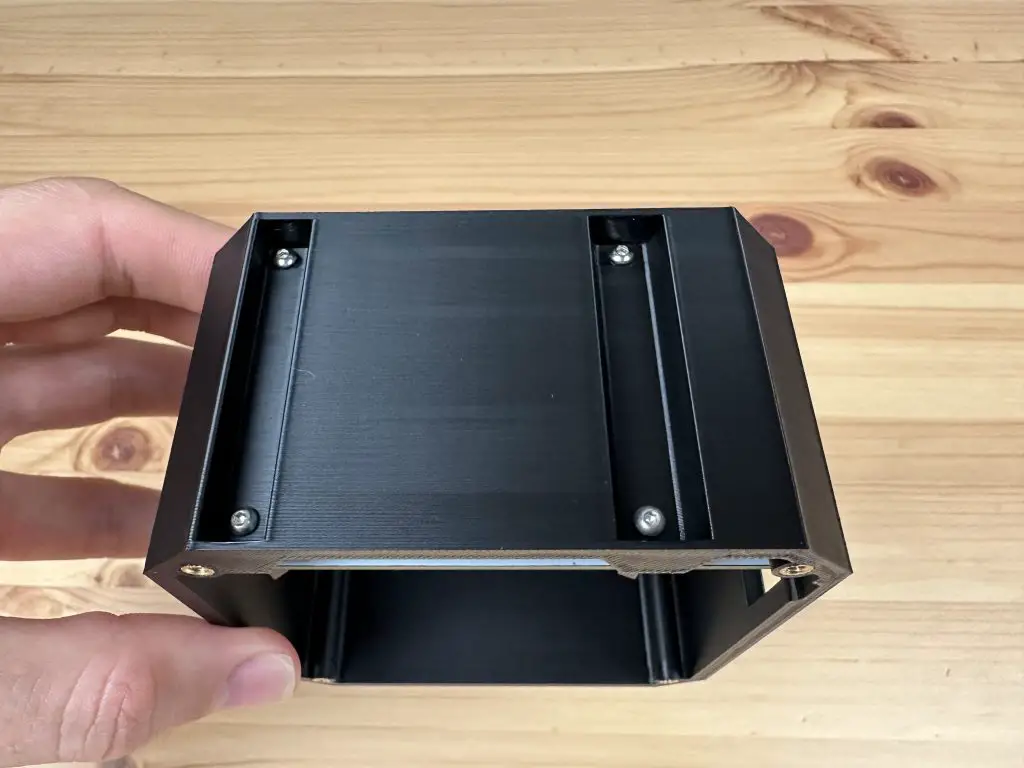

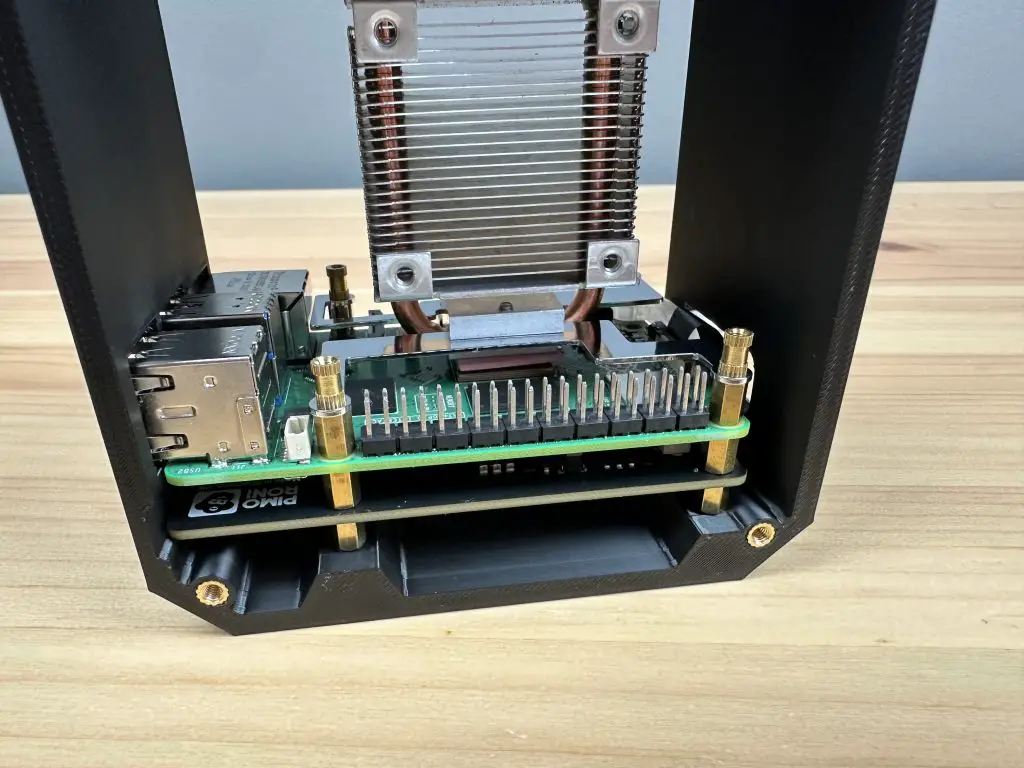

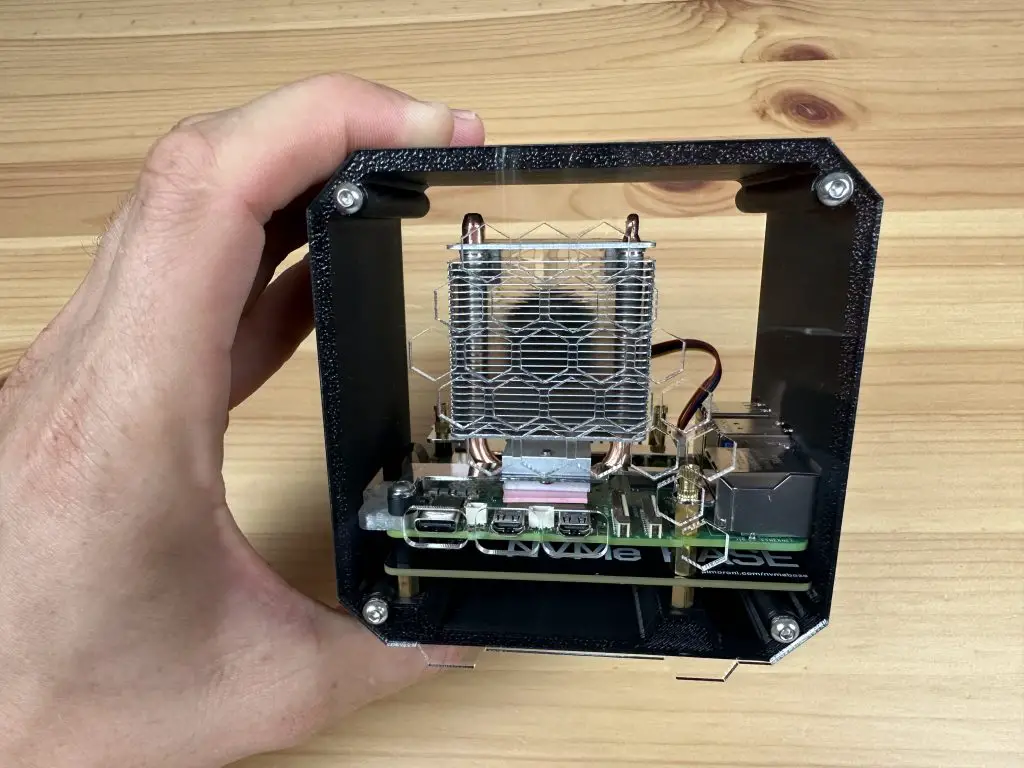

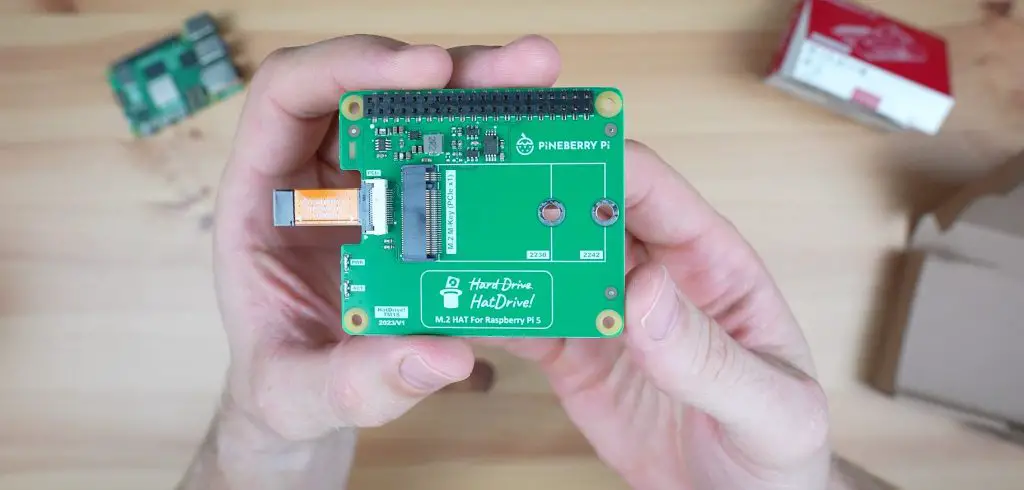

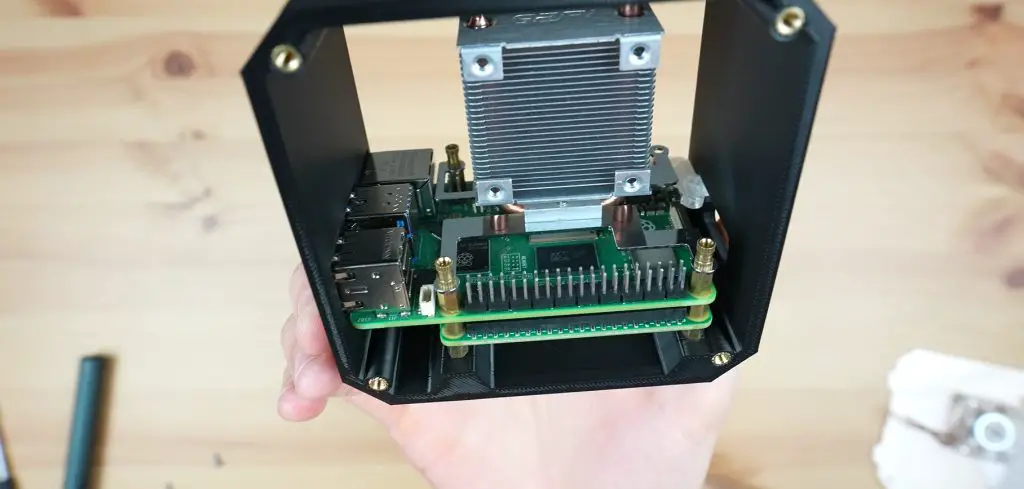

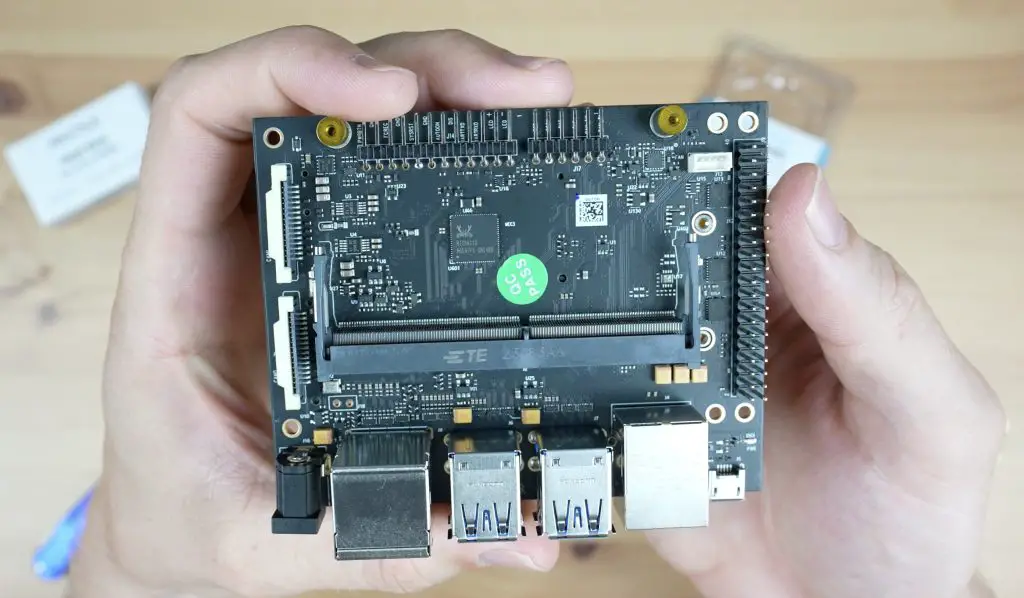

The carrier board that I’m going to be using with the Core 3588E is the A206, which is designed for NVIDIA Jetson modules.

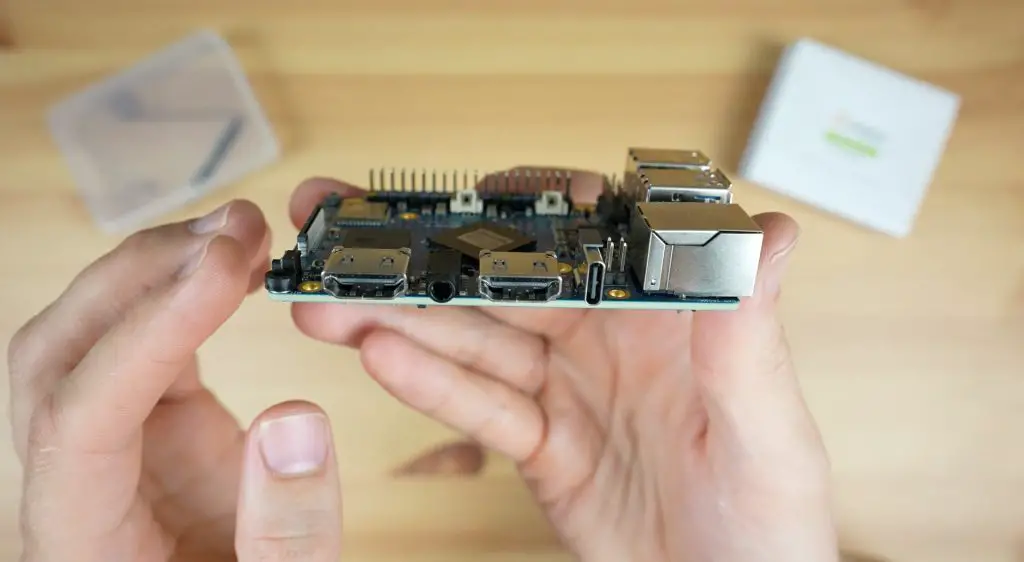

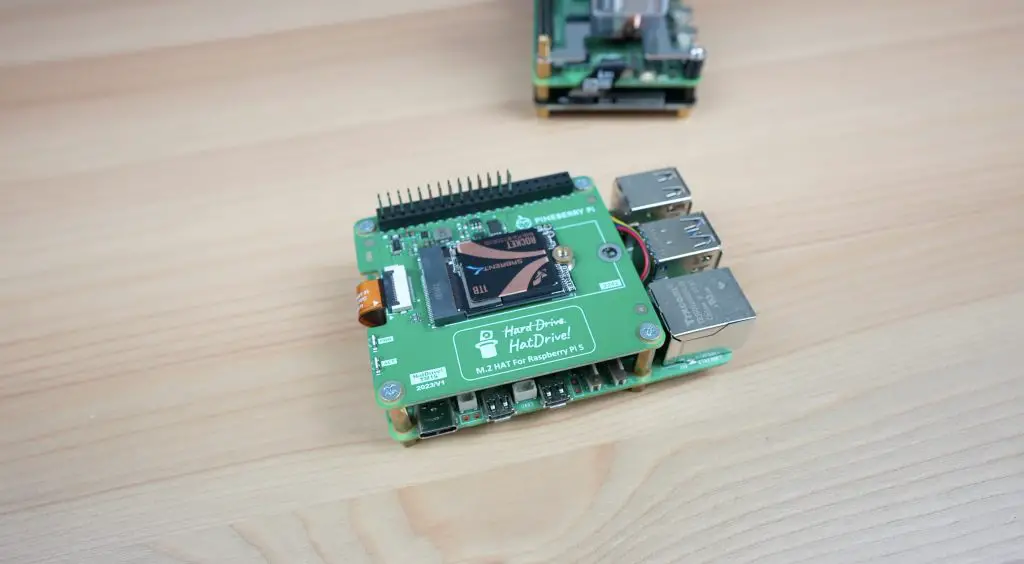

The main IO is all brought out on one side, with a power input on the left that supports a 9 to 19V DC supply. Alongside it, we’ve got a display port and HDMI port, 4 x USB 3.0 ports, and a Gigabit Ethernet port. The microUSB port at the end is for reflashing the boot loader.

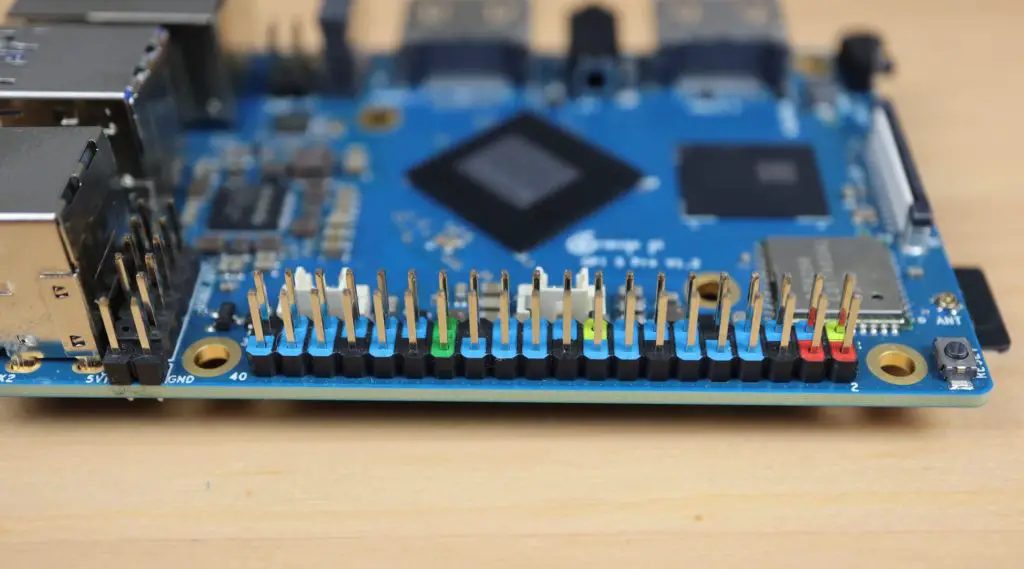

On the top of the carrier board, it has a set of GPIO pins along the right side, a set of pins for buttons and the CAN interface at the back and two camera inputs on the left.

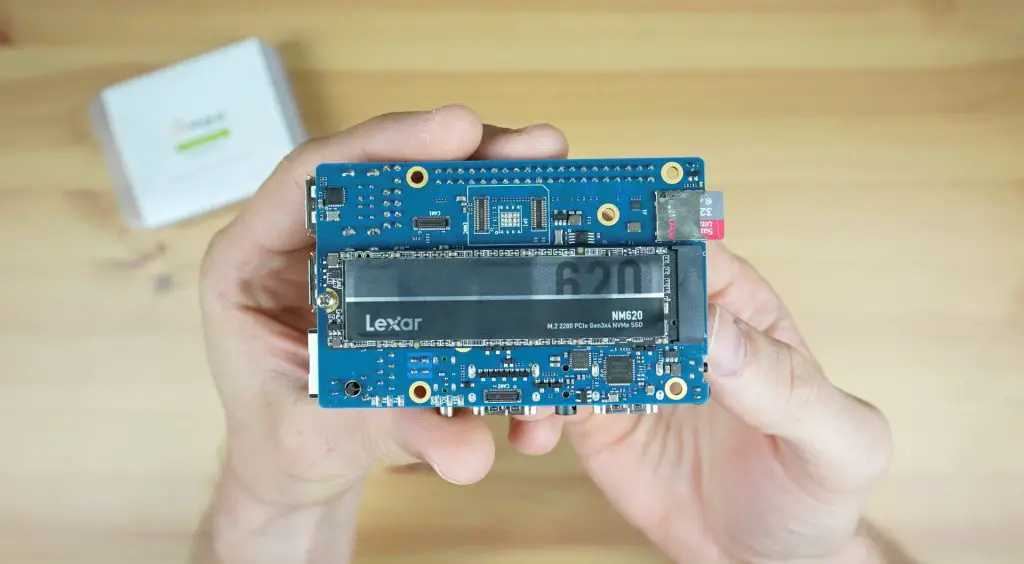

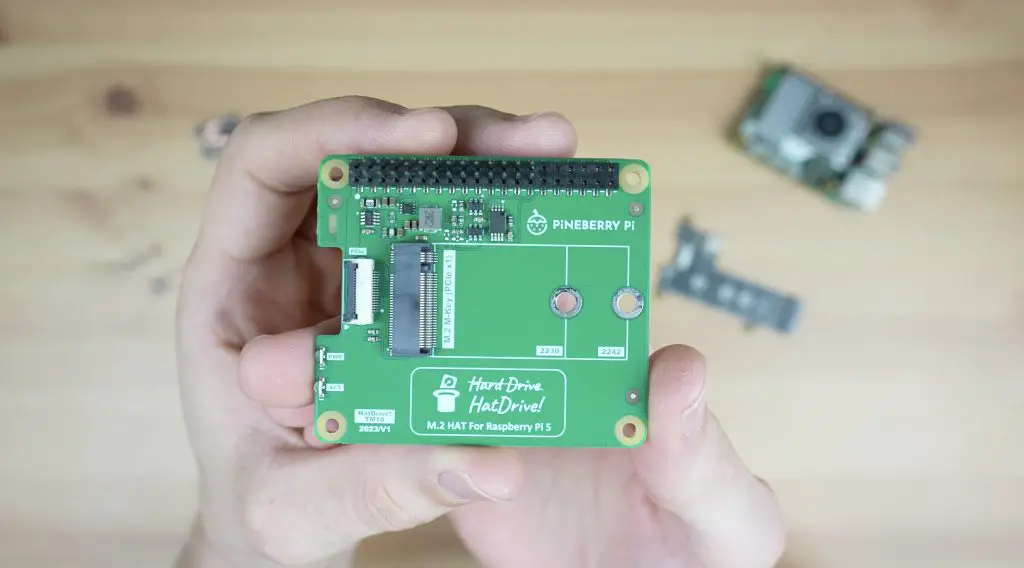

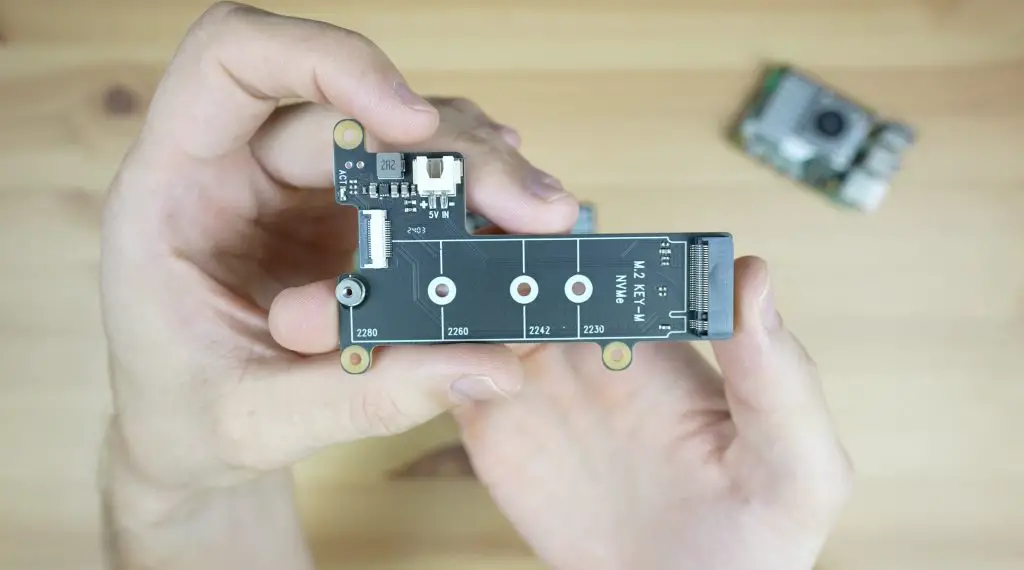

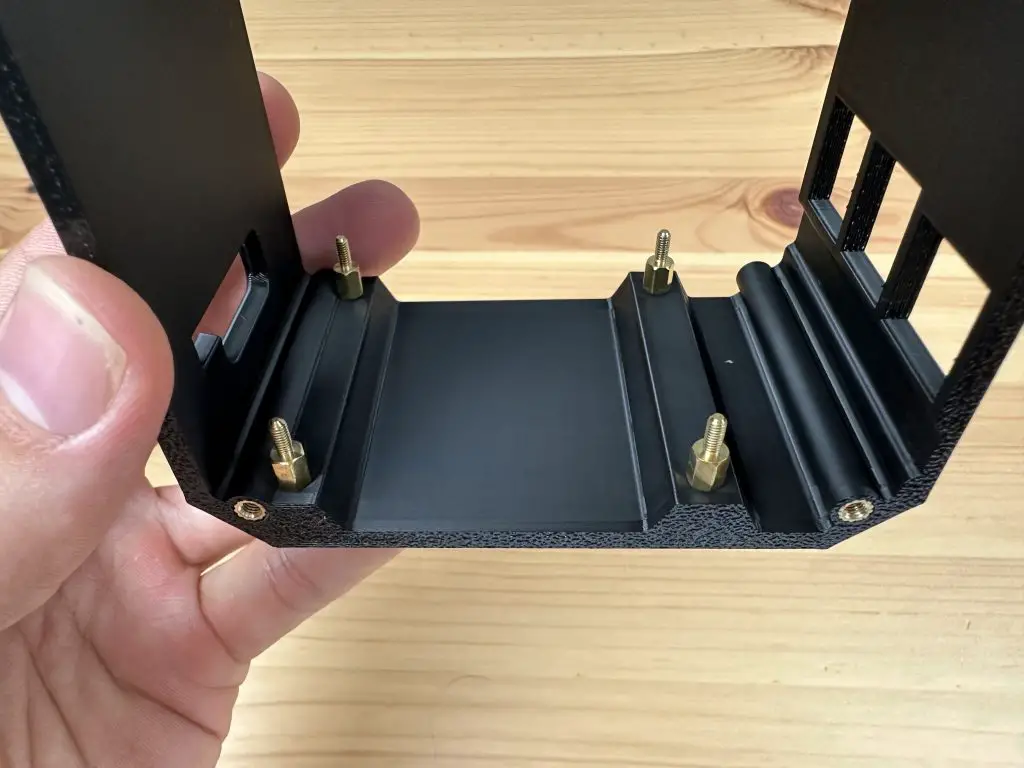

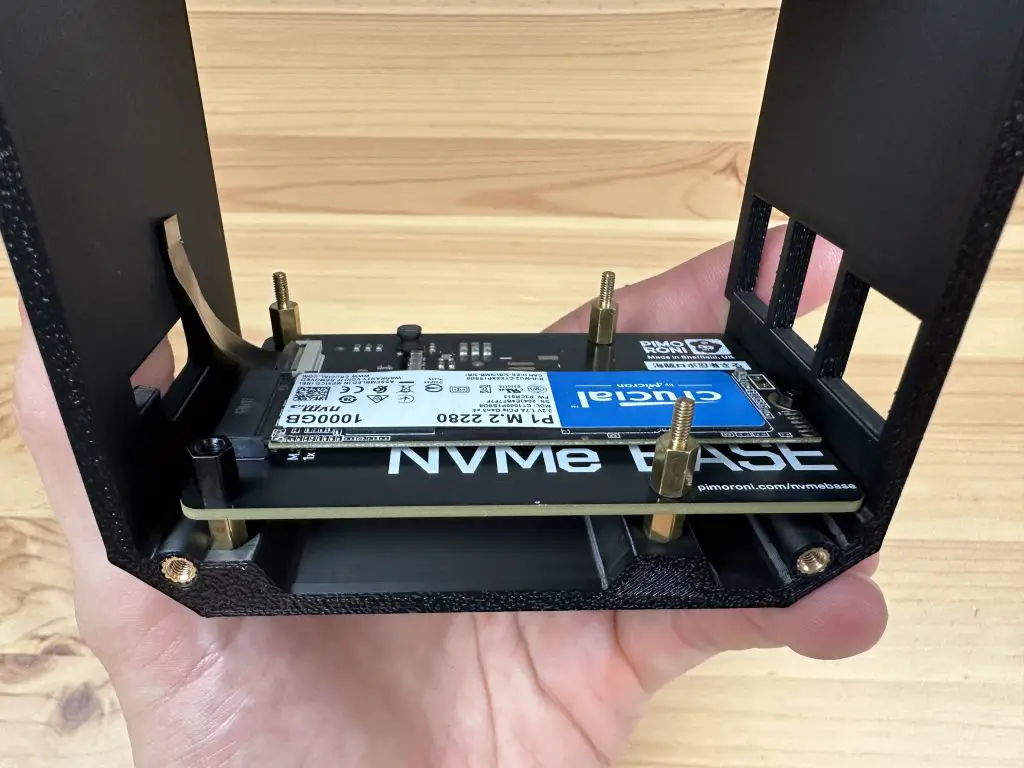

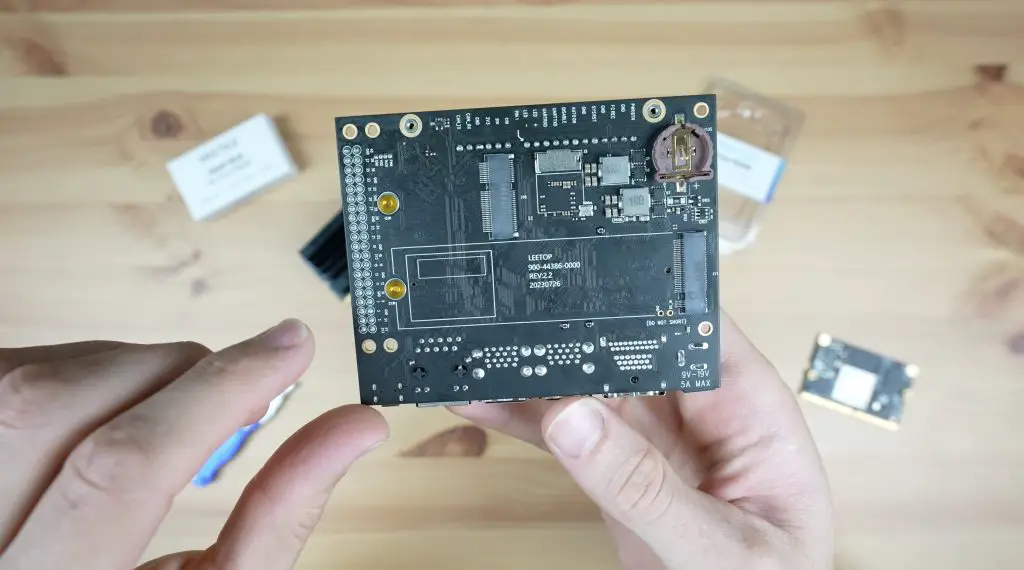

On the bottom is a M.2 E key port as well as an M.2 M key port, an RTC battery holder and a microSD card slot.

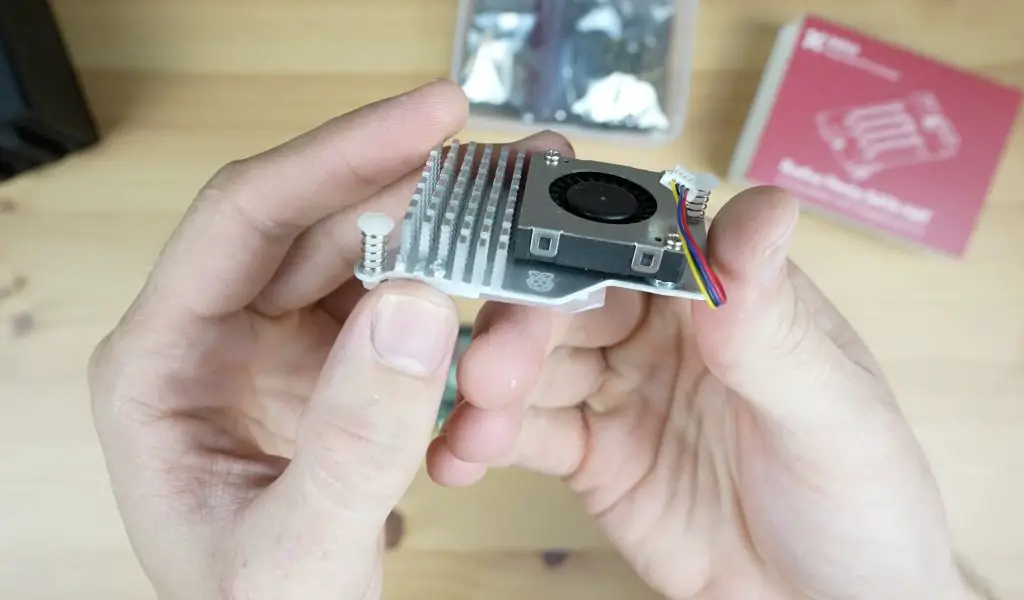

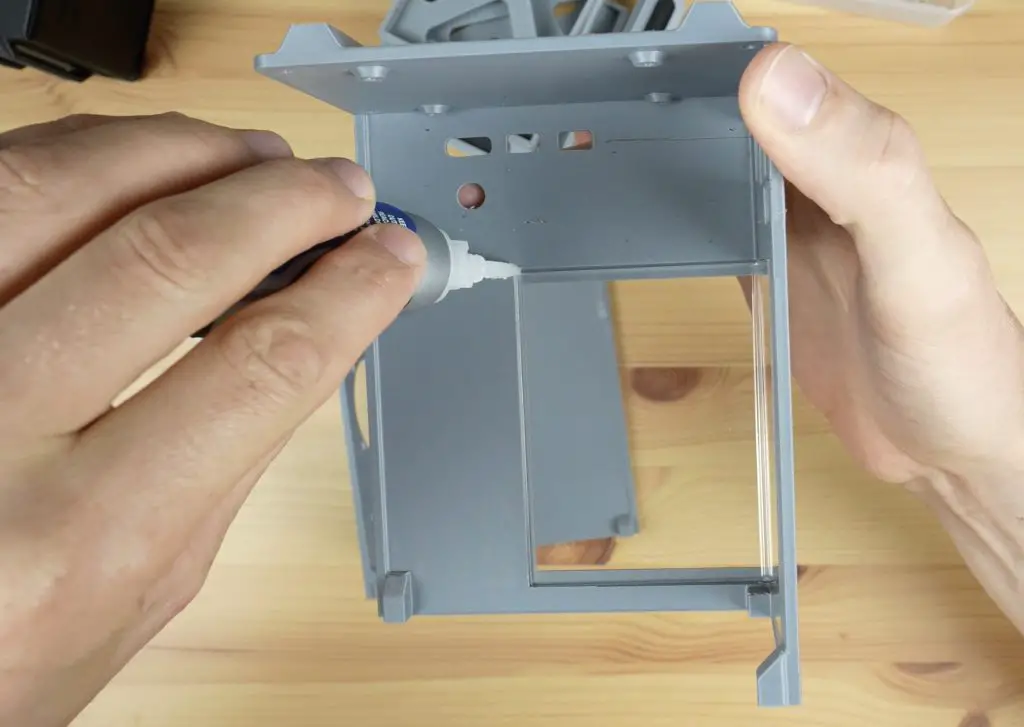

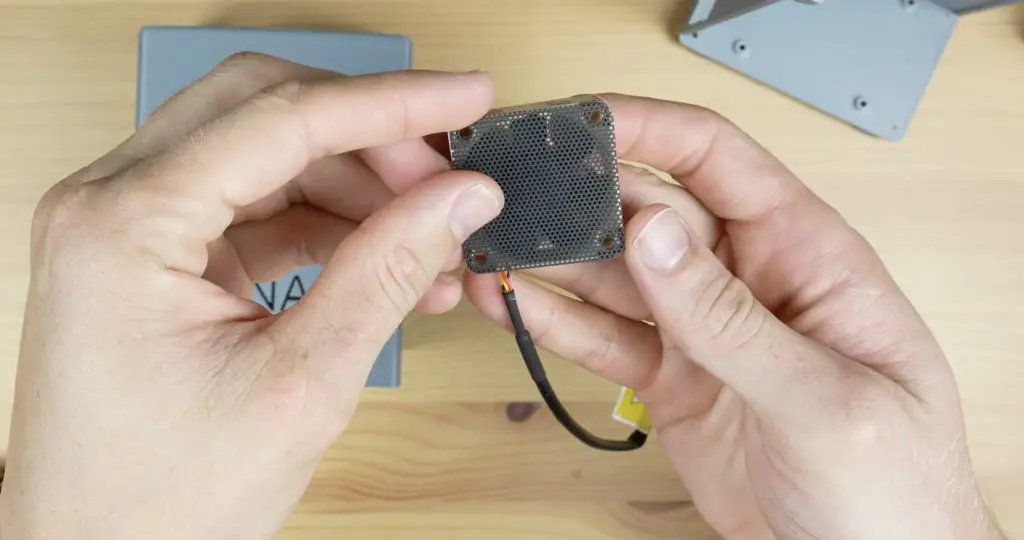

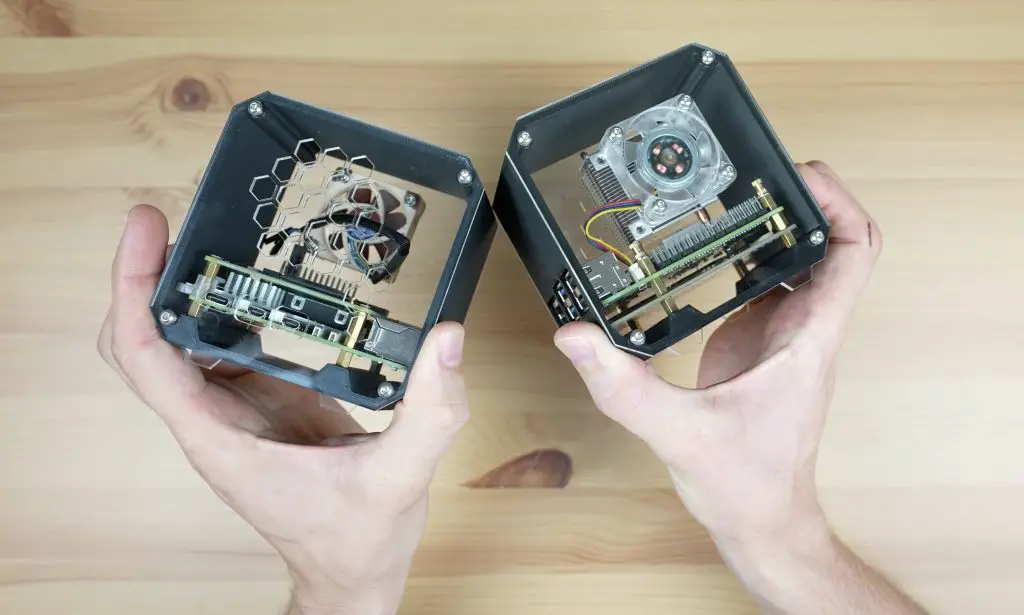

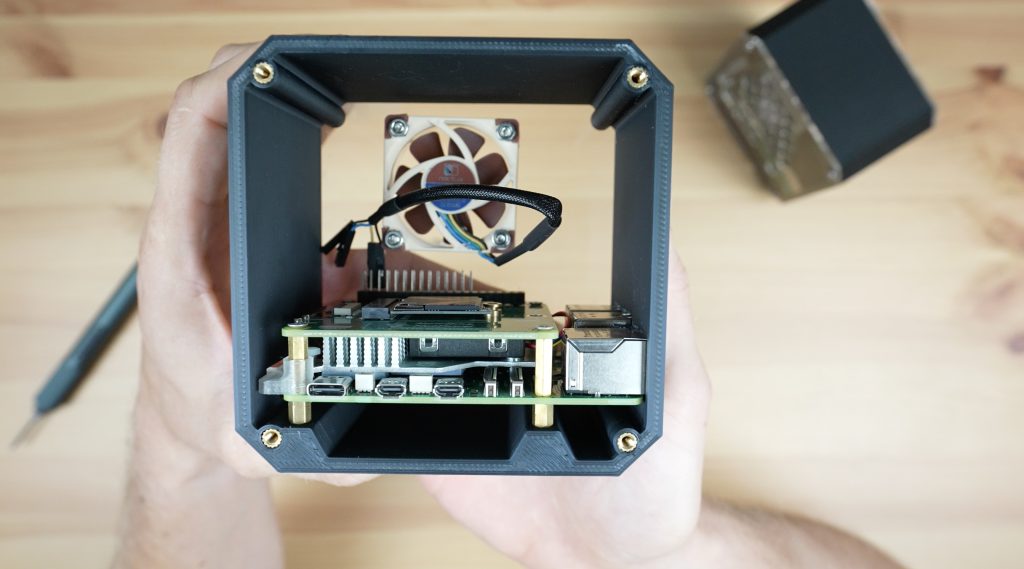

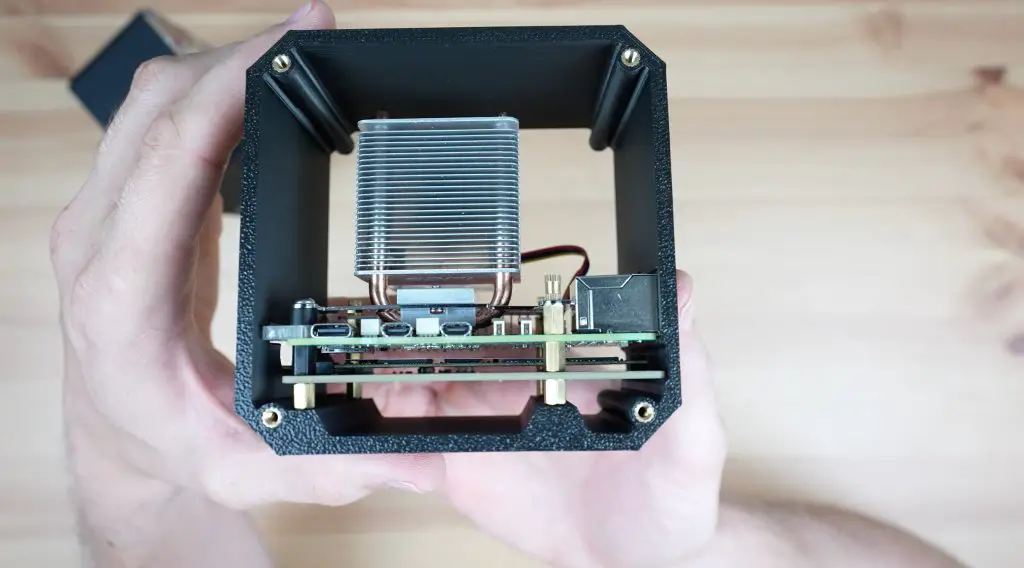

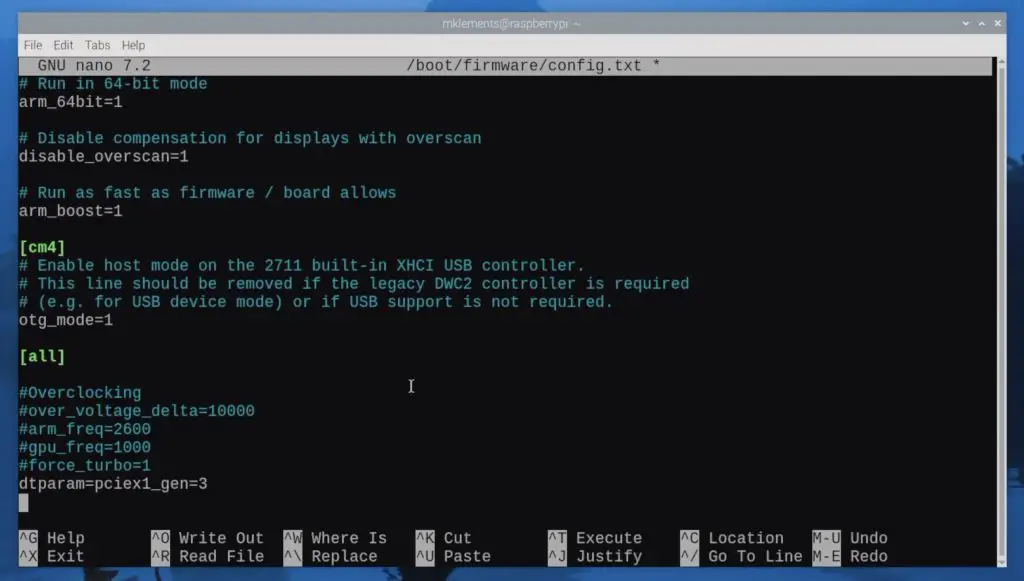

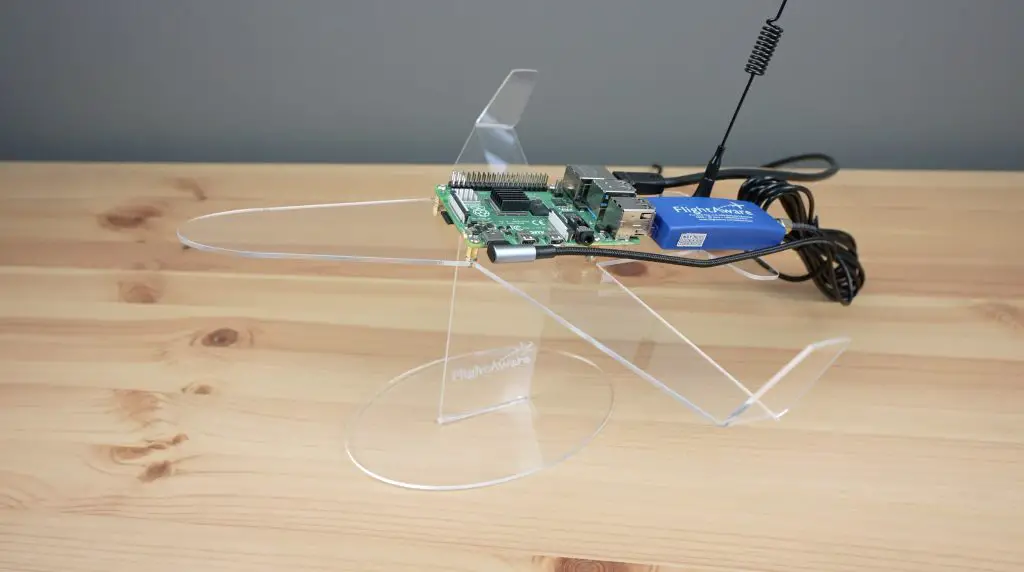

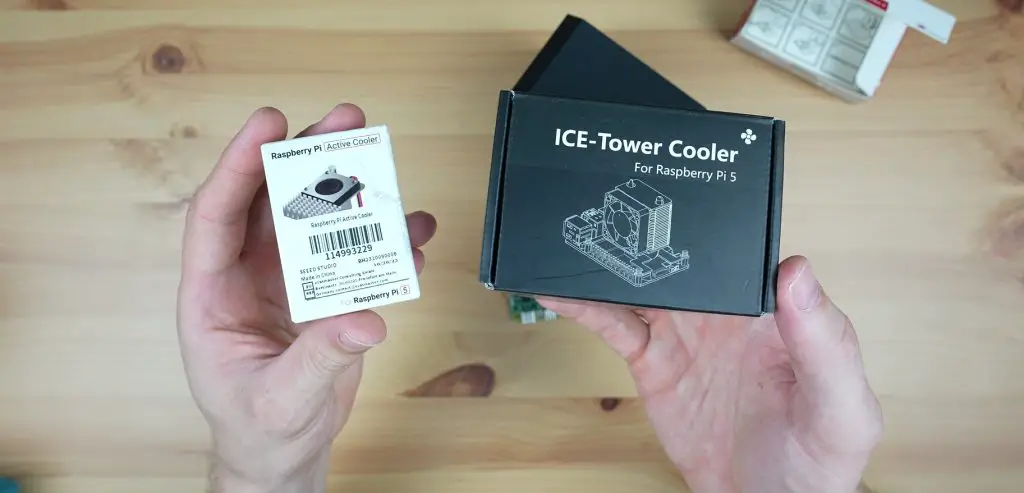

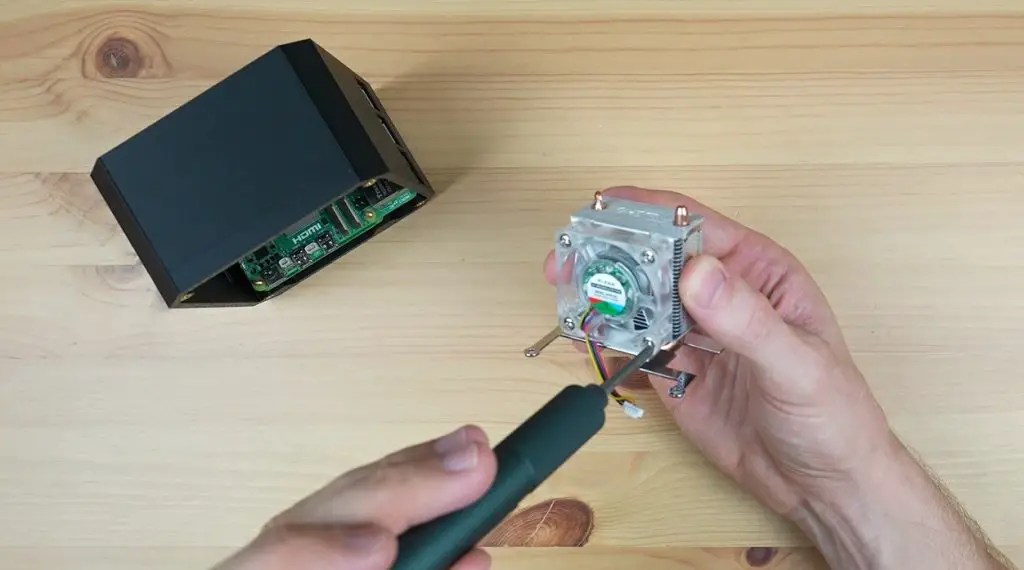

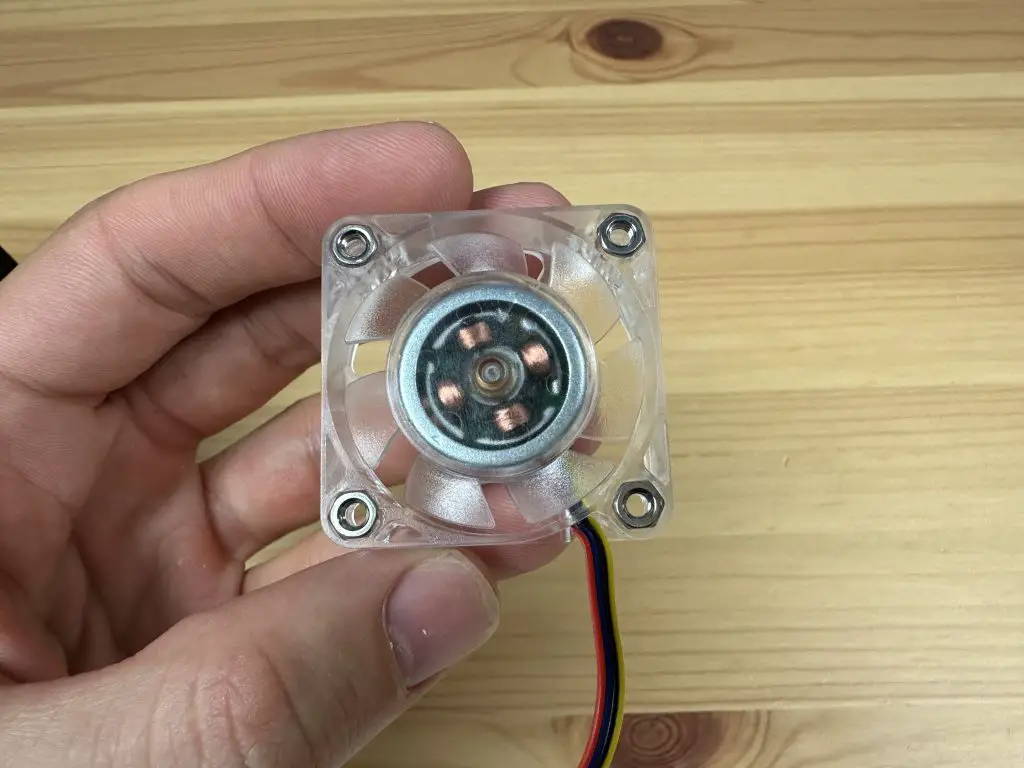

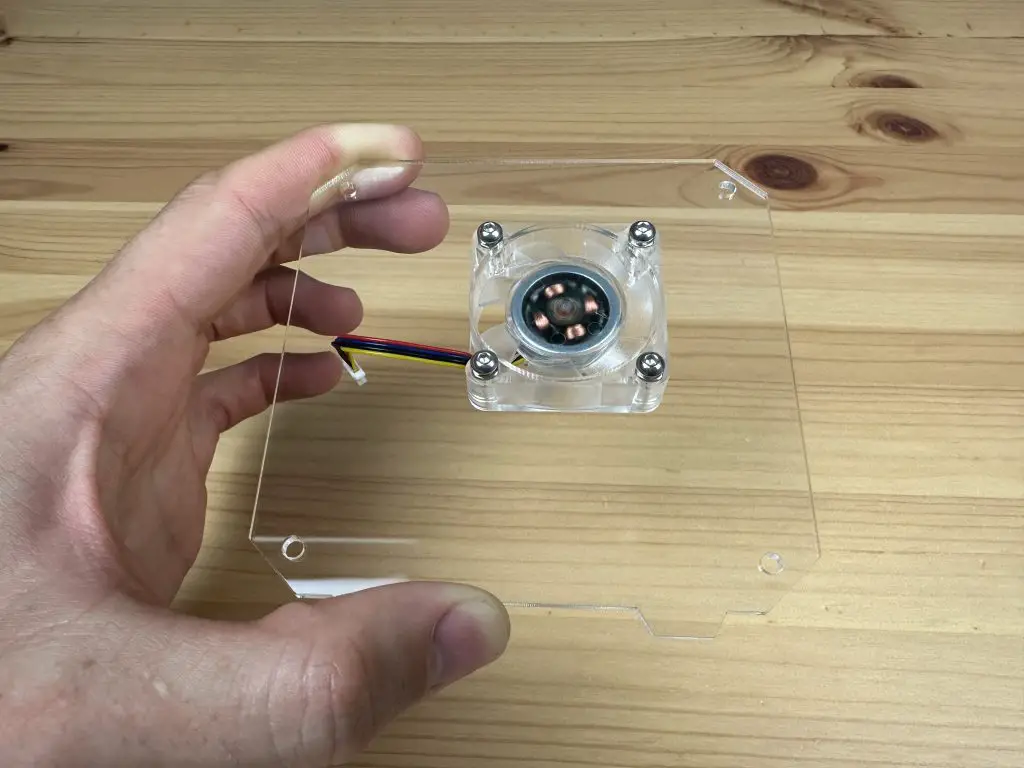

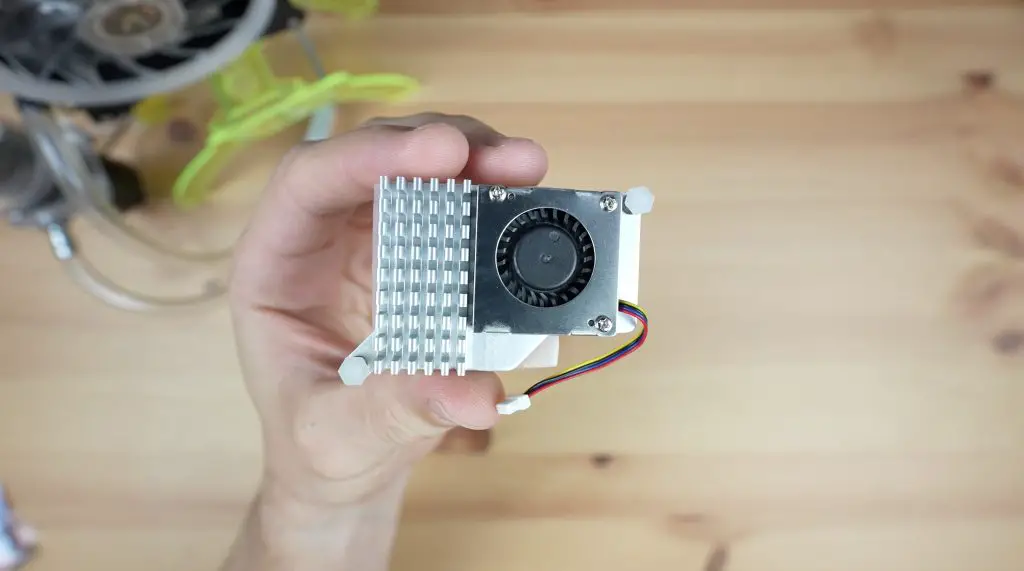

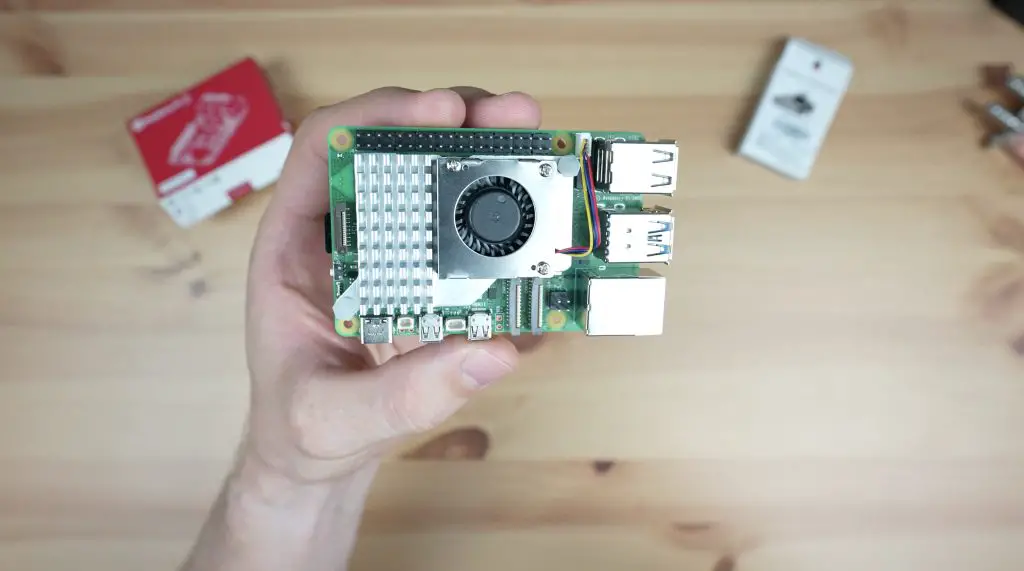

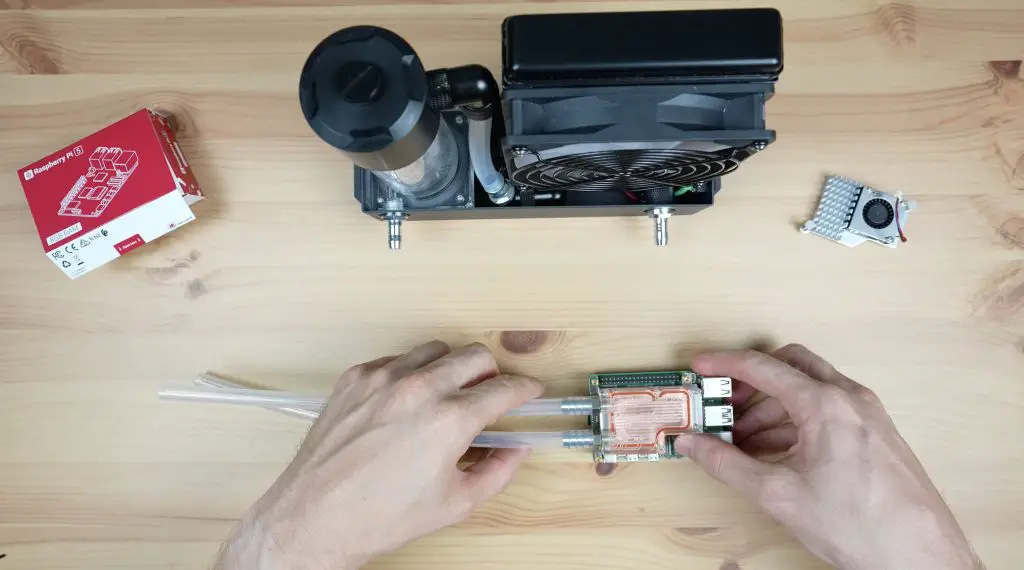

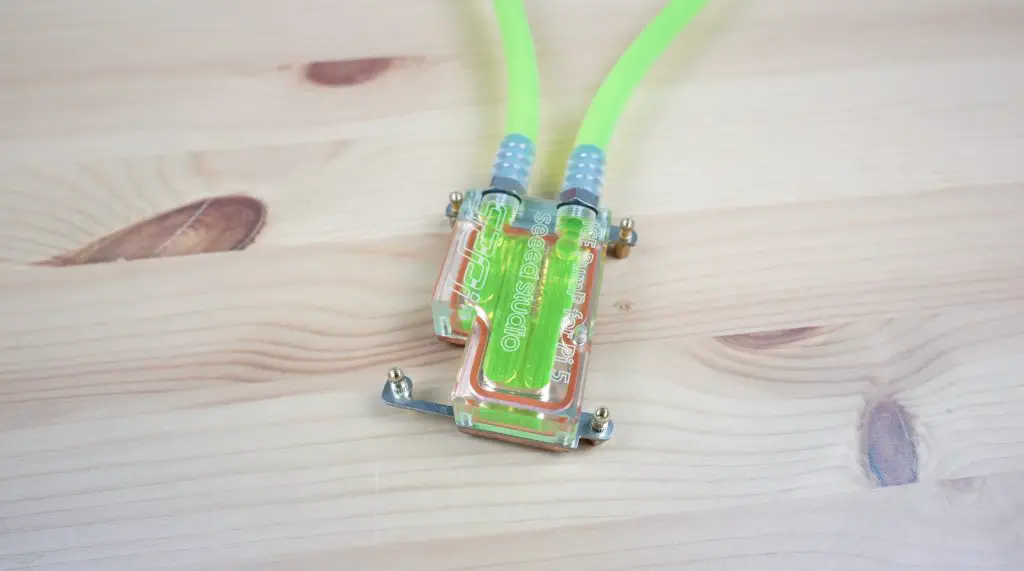

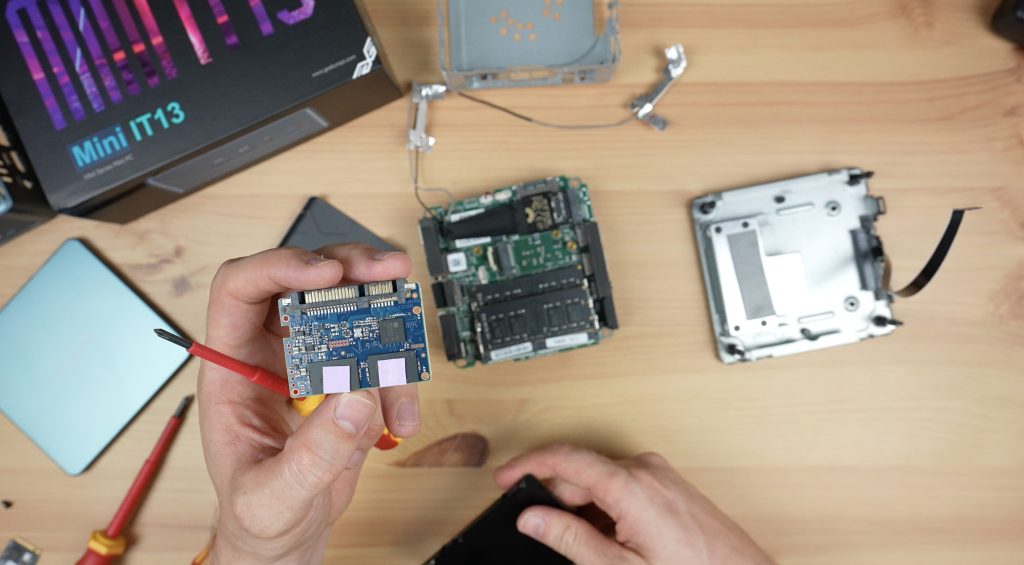

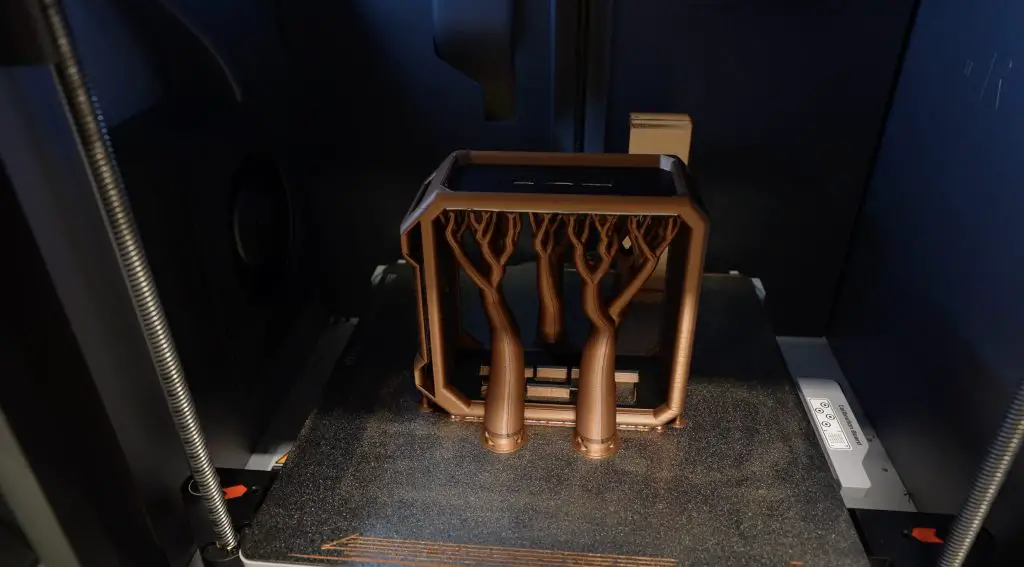

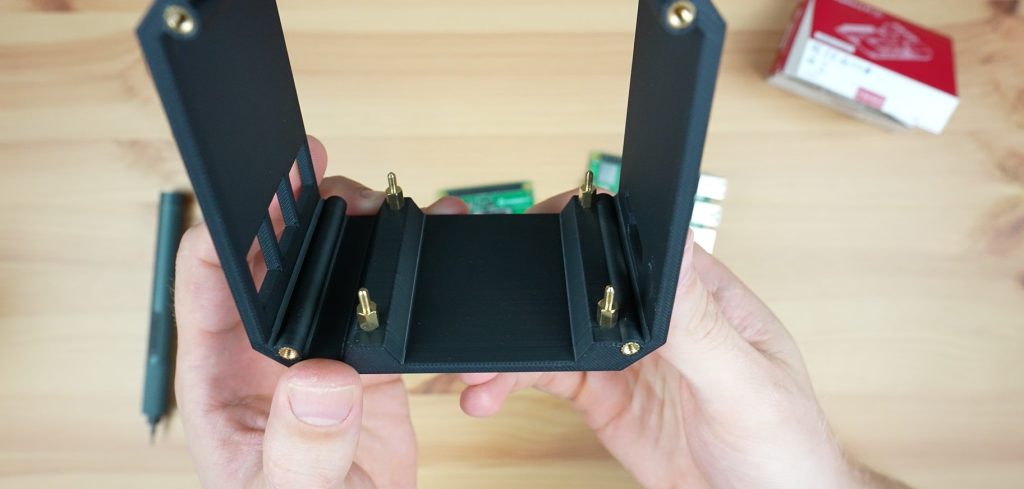

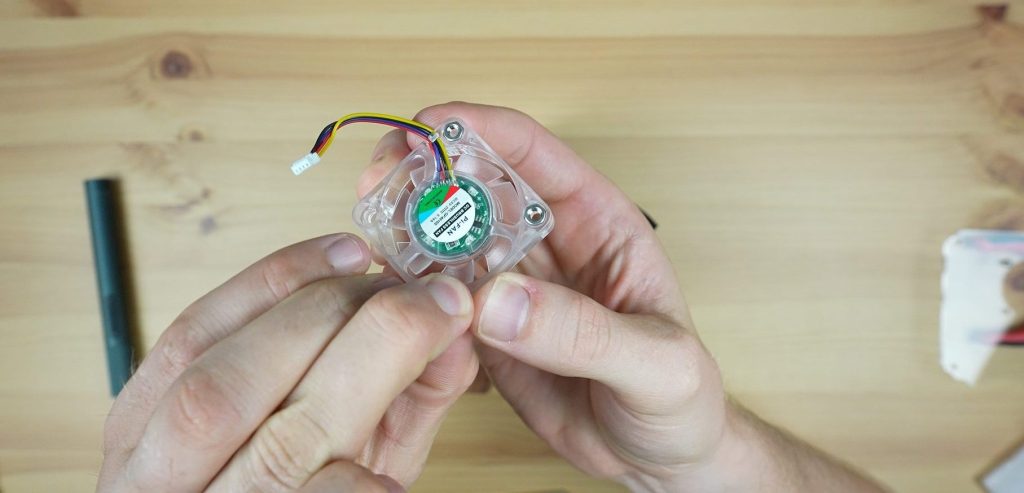

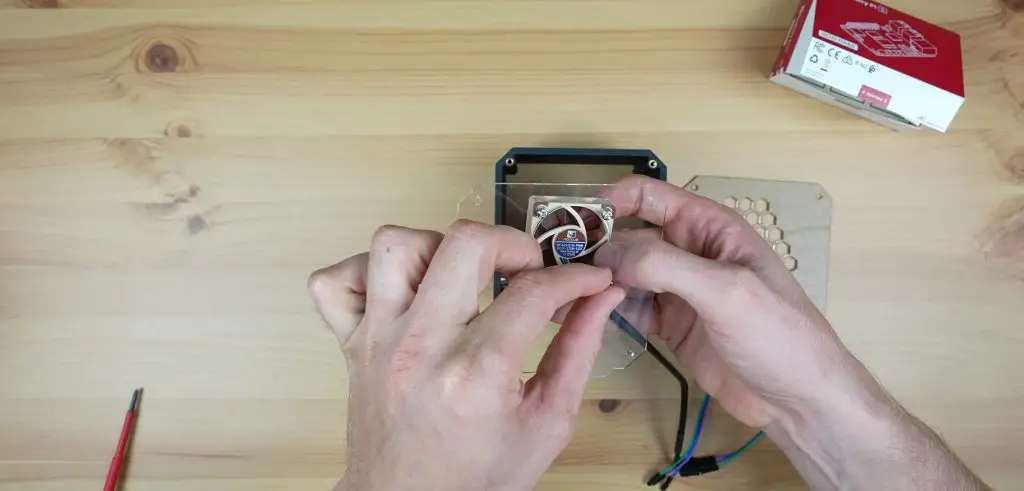

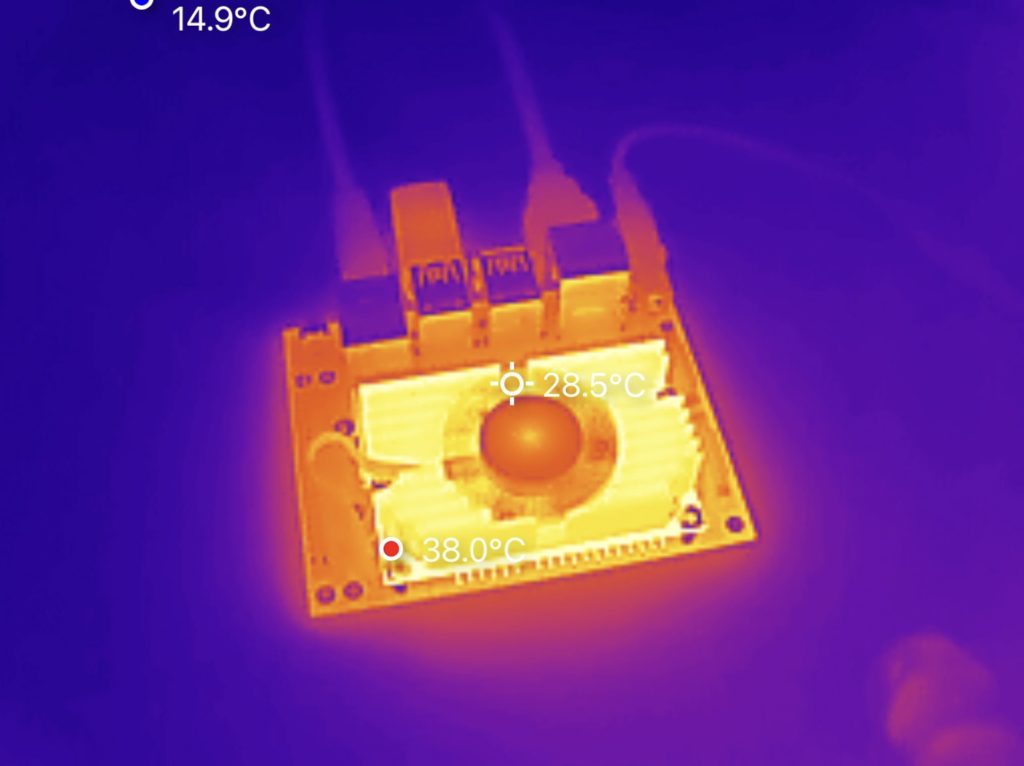

Also available for the Core 3588E is an optional heatsink with a built-in PWM fan which plugs into the carrier board. The heatsink is attached directly to the Core 3588e with some small screws that go into thread inserts on the SOM. They provide thermal paste to apply between the CPU and heatsink for improved conductivity.

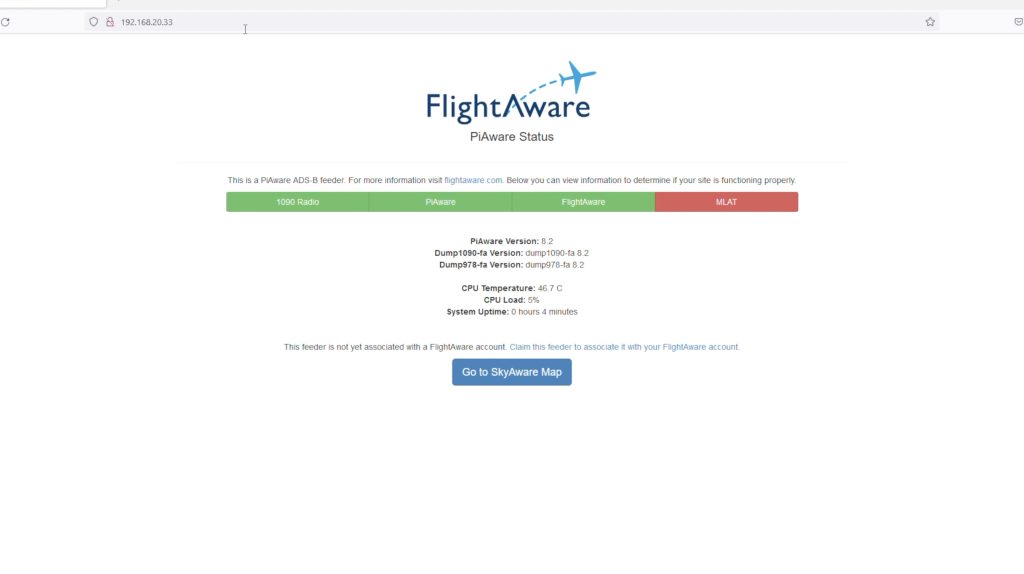

First Boot & Testing

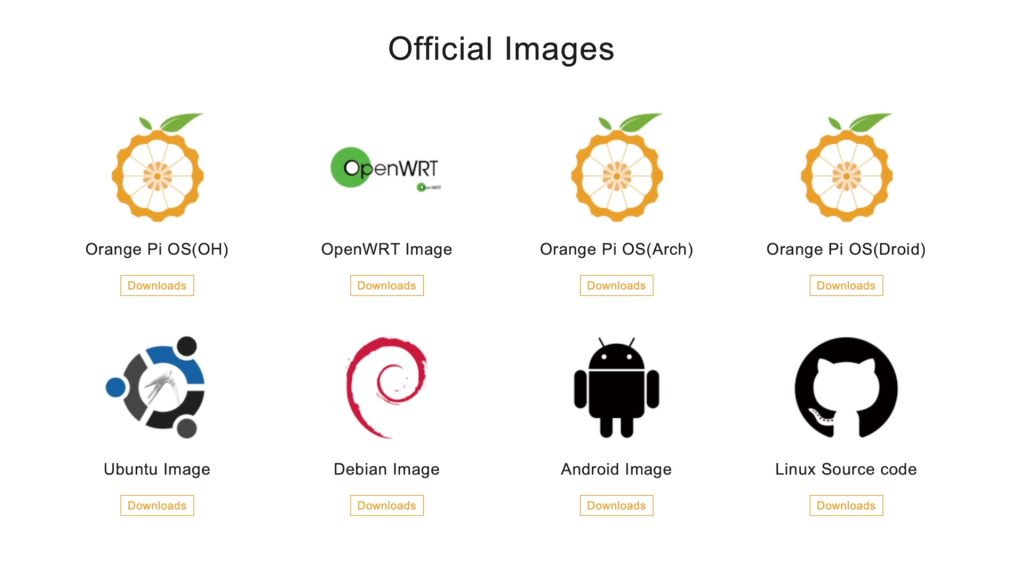

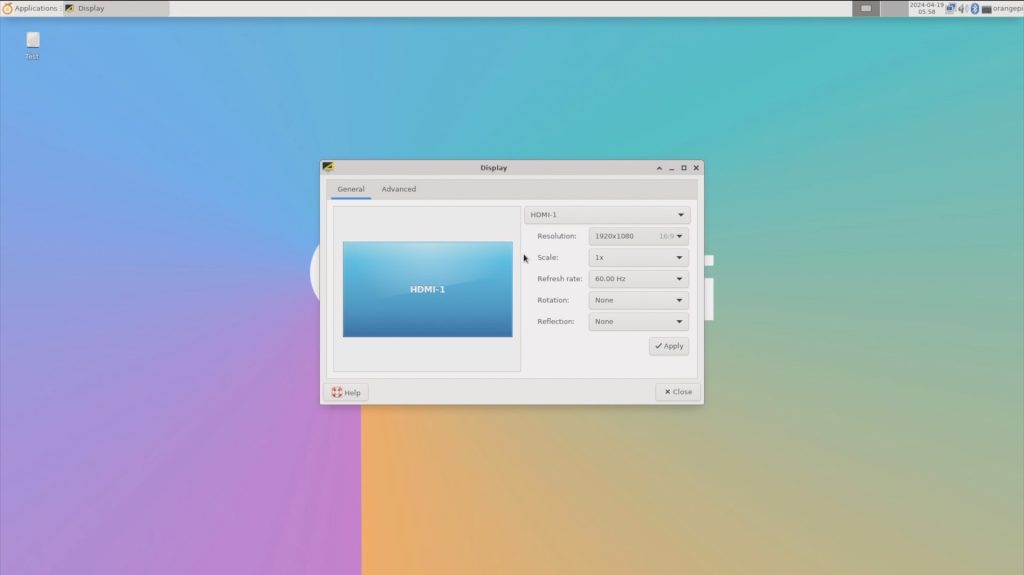

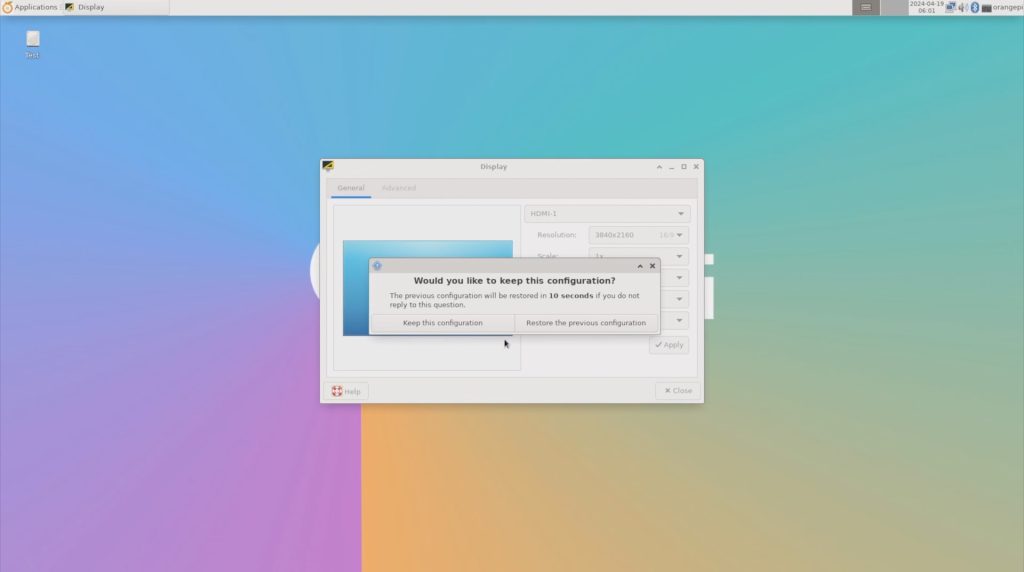

The board comes preloaded with a custom Ubuntu desktop image, so it’s ready to run right out of the box. You can also compile your own images for Debian and Android.

I’m going to test this board in a similar way to other SBCs that I’ve tried on this channel. I’ll also show you it running a pre-trained AI model to recognise objects in images as this is primarily what these modules are intended to be used for.

We’ll first test some video playback at 1080P, then try to run a Sysbench benchmark, then run a storage speed test, then the AI object detection model and finally we’ll take a look at power consumption.

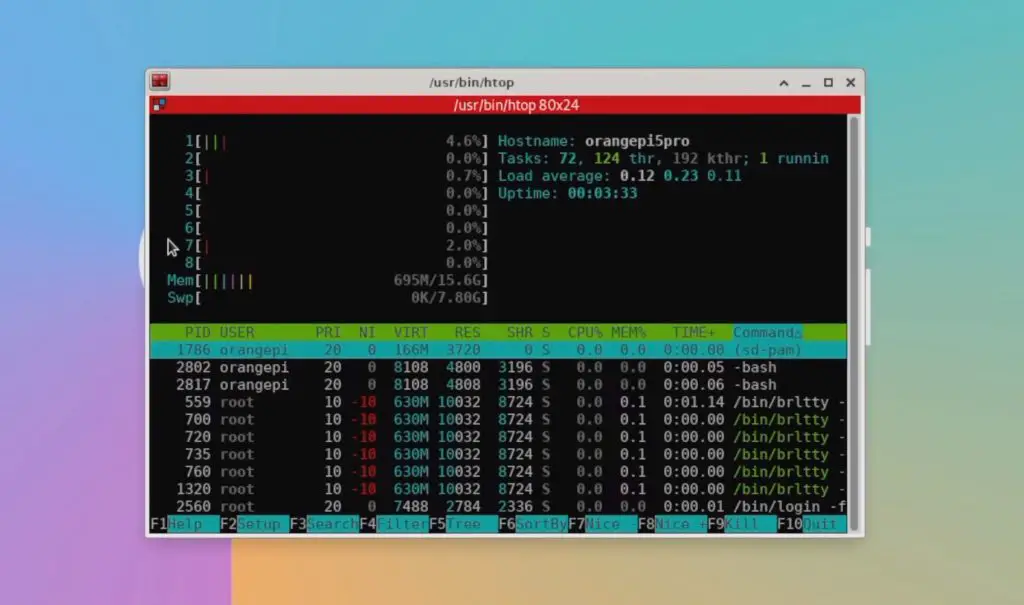

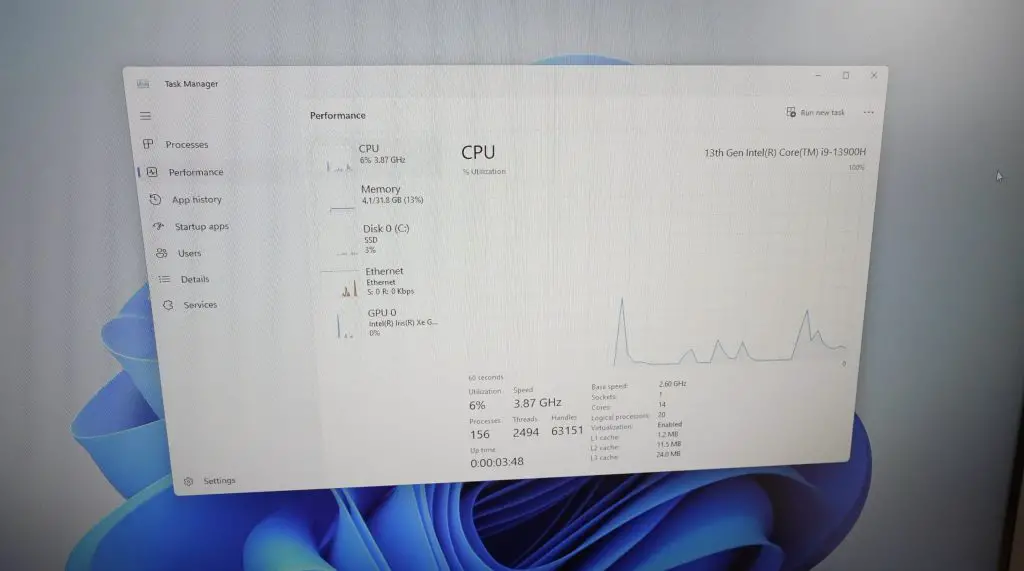

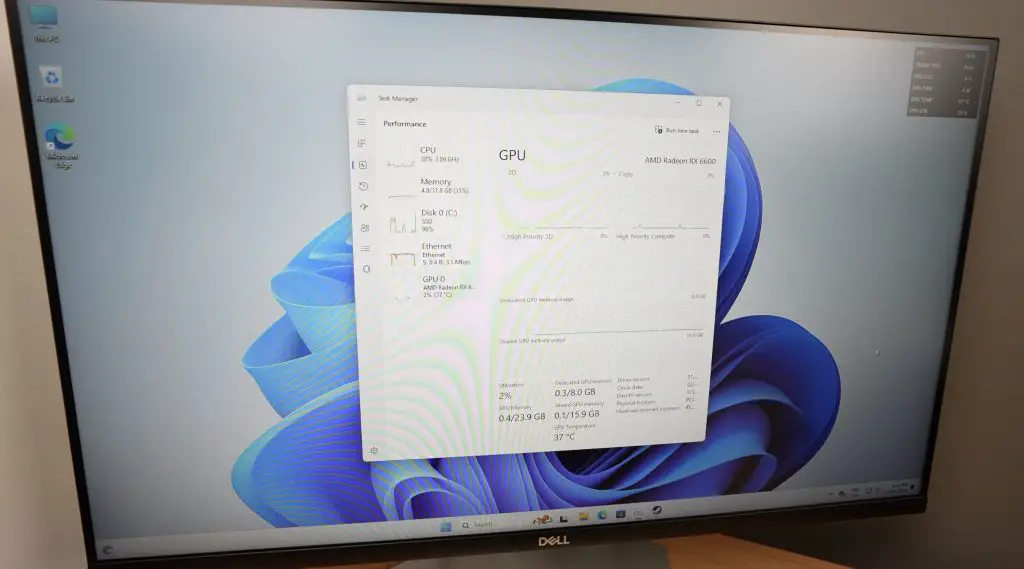

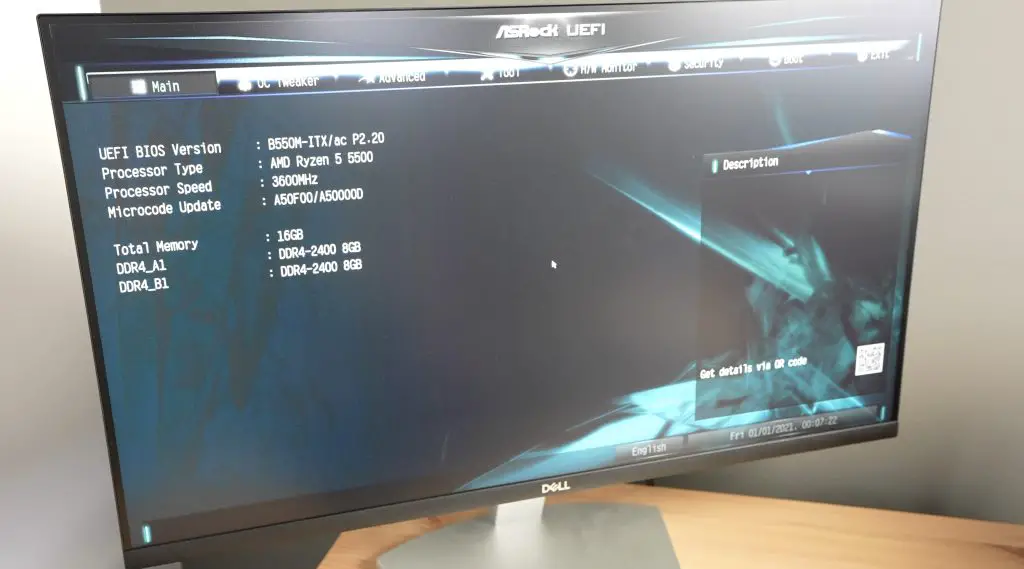

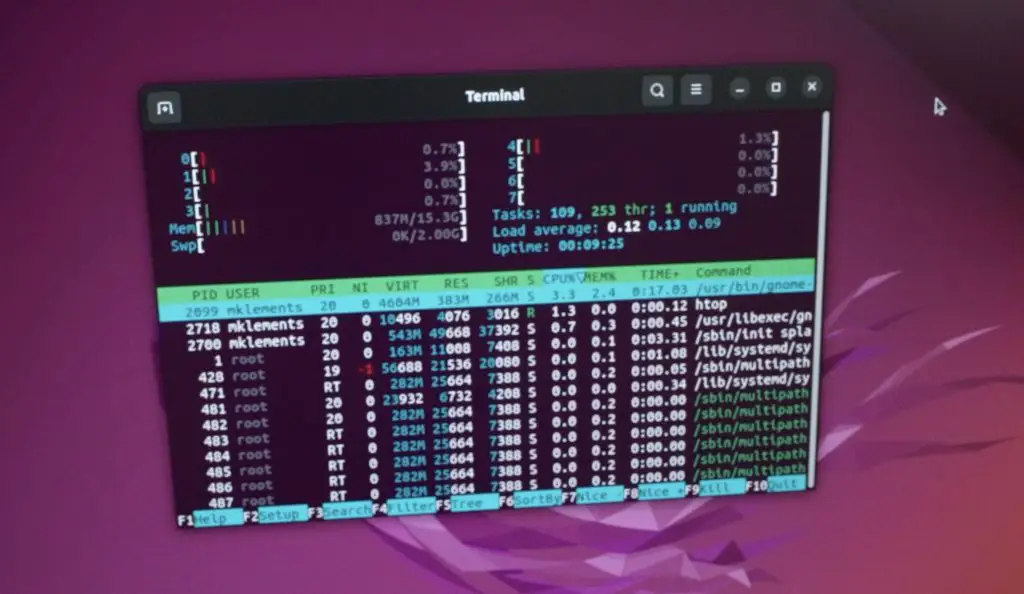

After the Mixtile Core 3588e has booted up, if we open up HTOP, we can see we have 8 processor cores and our 16GB of RAM. The processor is currently under very little load, being idle on the desktop.

Video Playback At 1080P

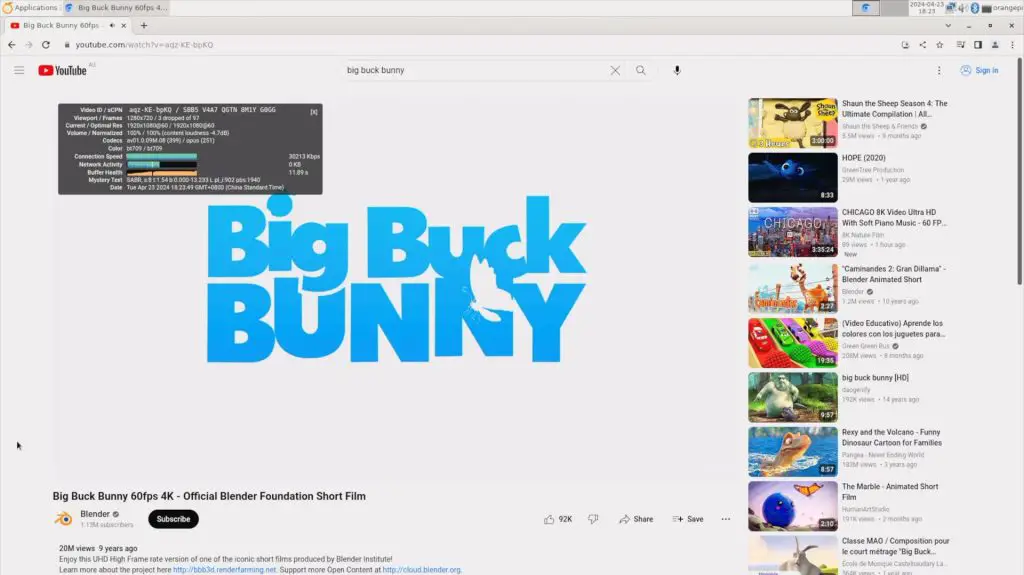

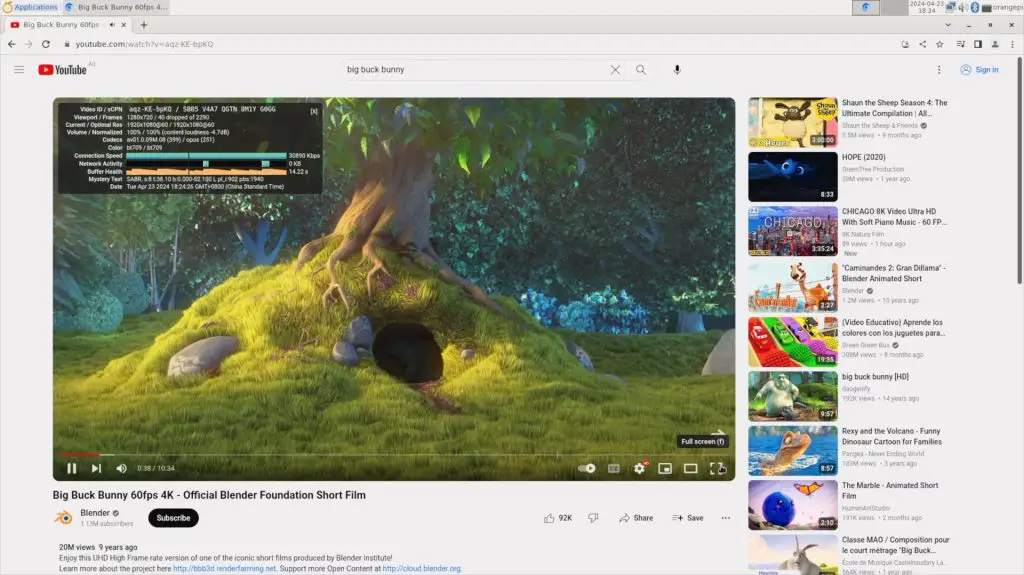

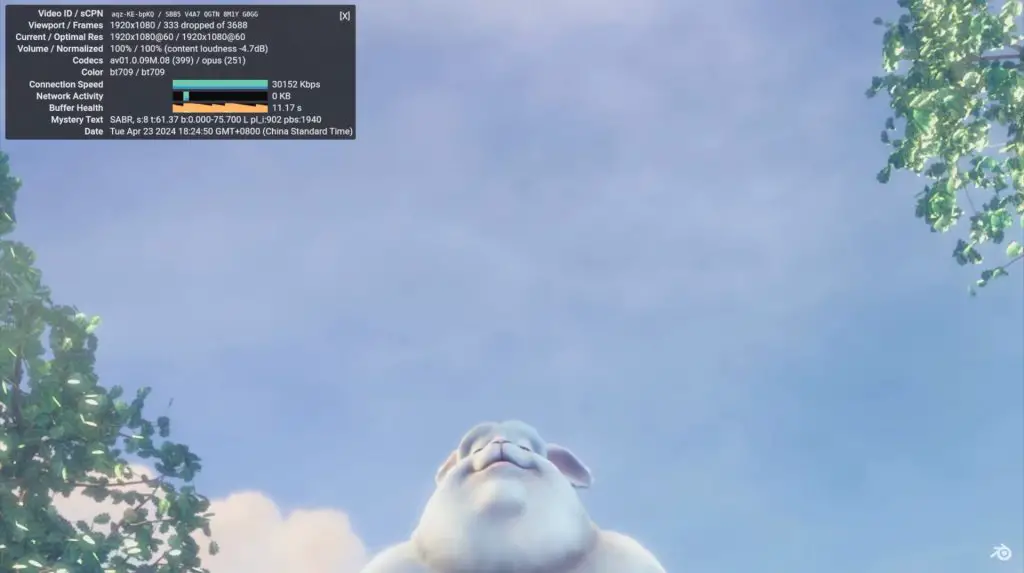

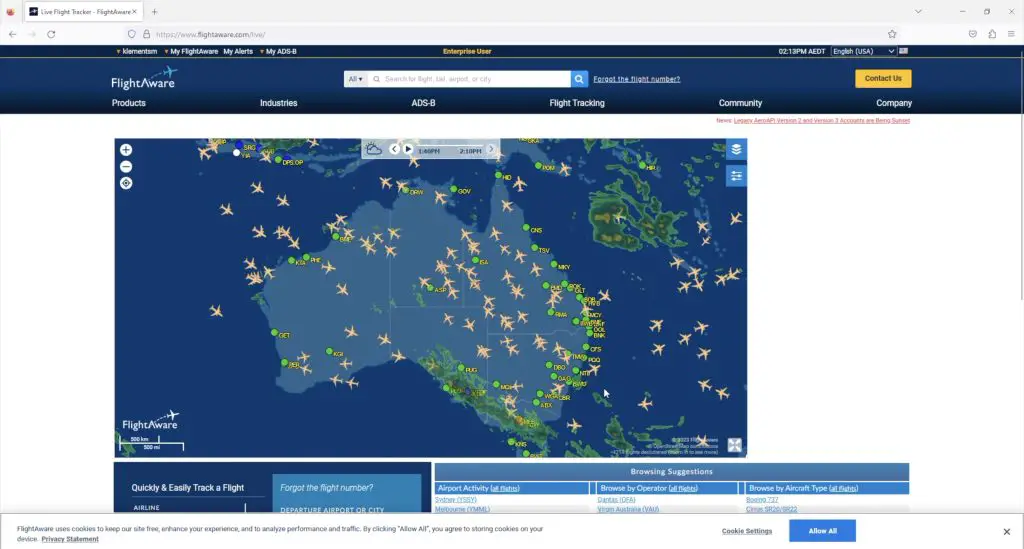

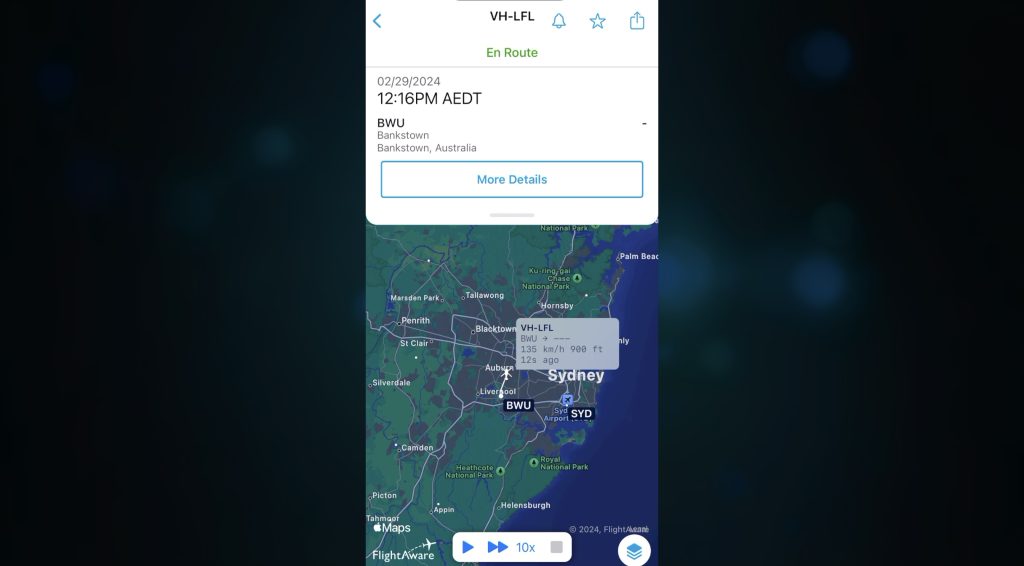

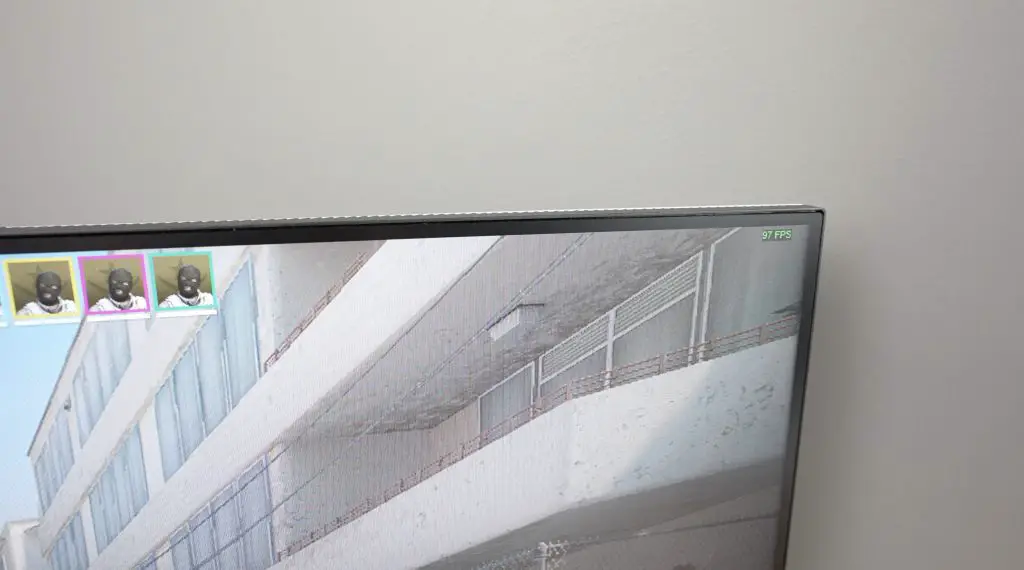

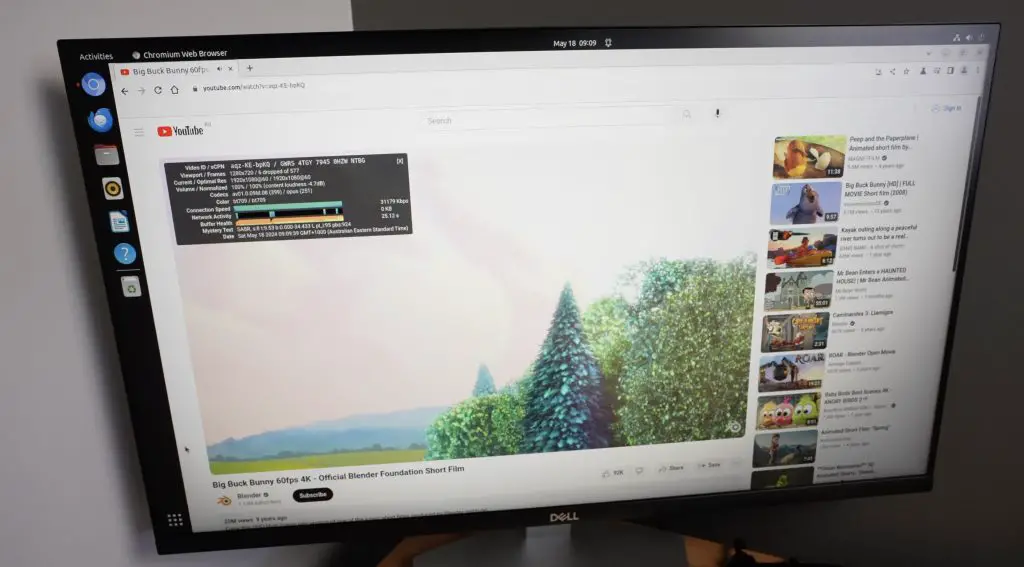

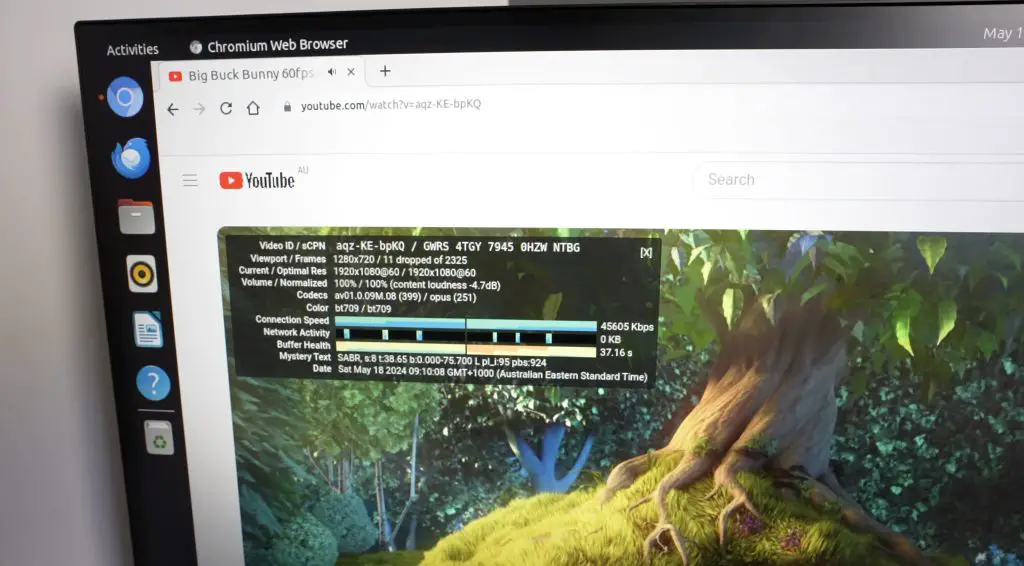

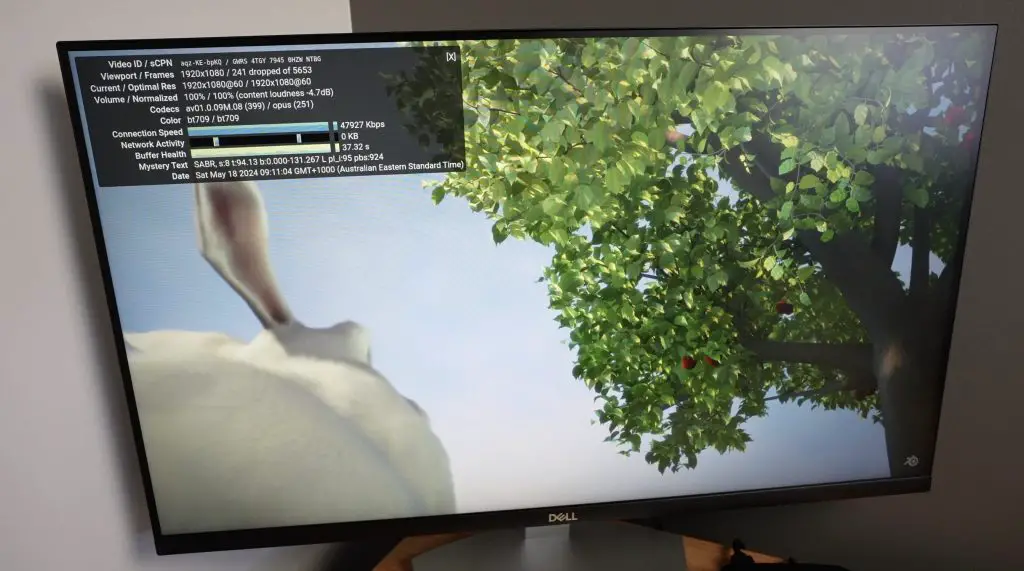

First let’s try playing back a YouTube video in Chromium, which I’m going to do at 1080P. We can open up Chromium, go to YouTube and play Big Buck Bunny. I’ll open up stats for nerds and set the playback resolution to 1080P as well.

Video playback in the window is pretty good. We dropped quite a few frames in the beginning but after that playback settles and is very stable and usable.

It’s also pretty good running full screen. It again dropped quite a few frames in the beginning and then settled down.

If we open up HTOP, we can see that we’re averaging less than 30% CPU utilisation on the first 4 cores, which is relatively low compared to the other RK3588 boards that I’ve tested.

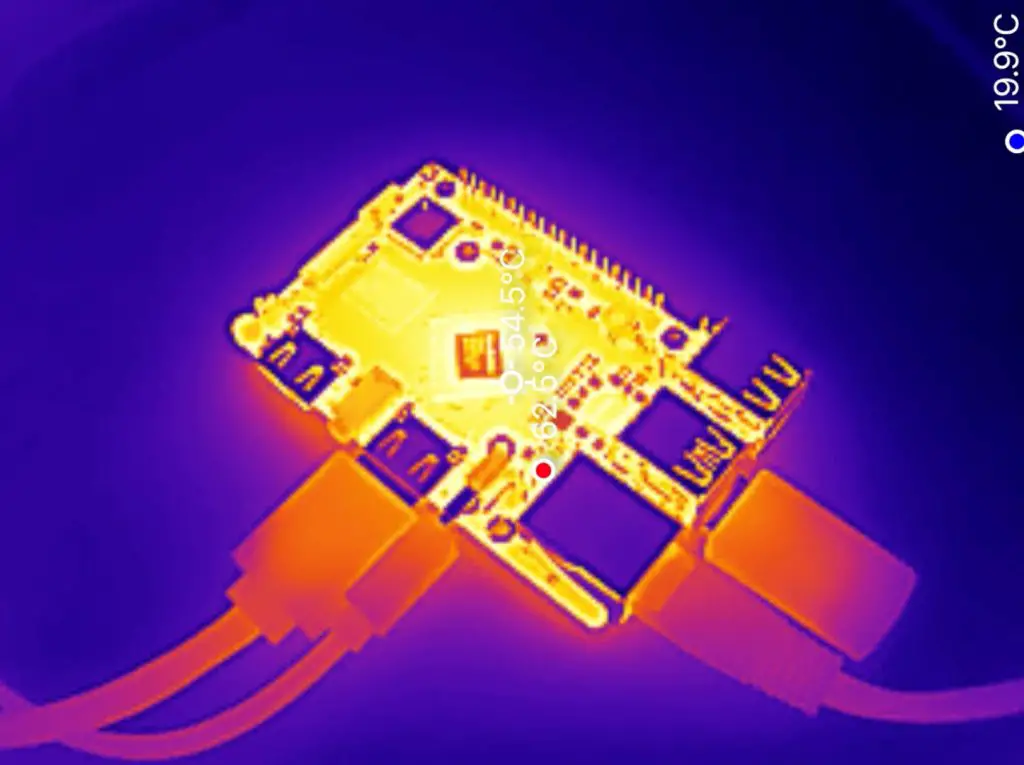

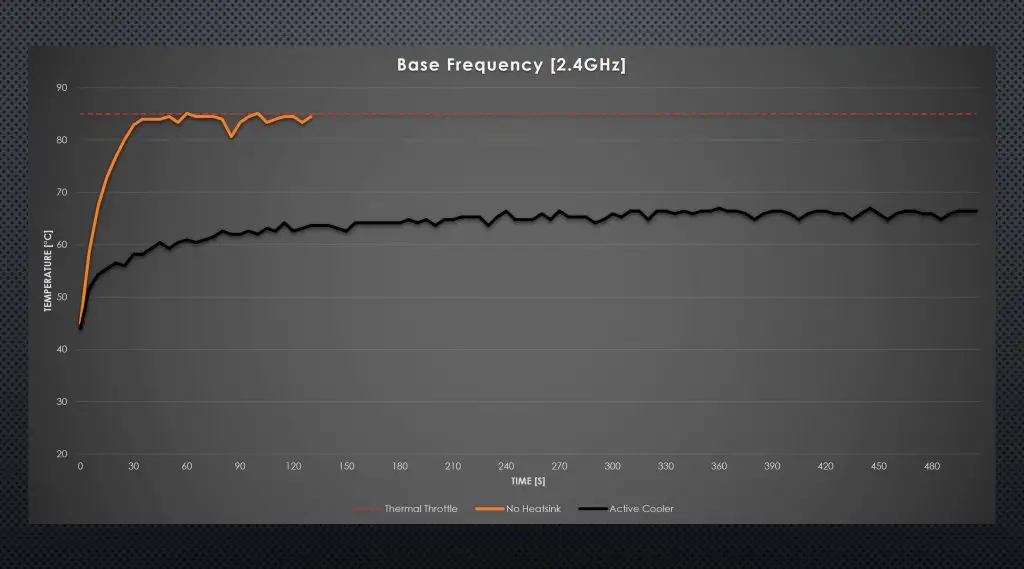

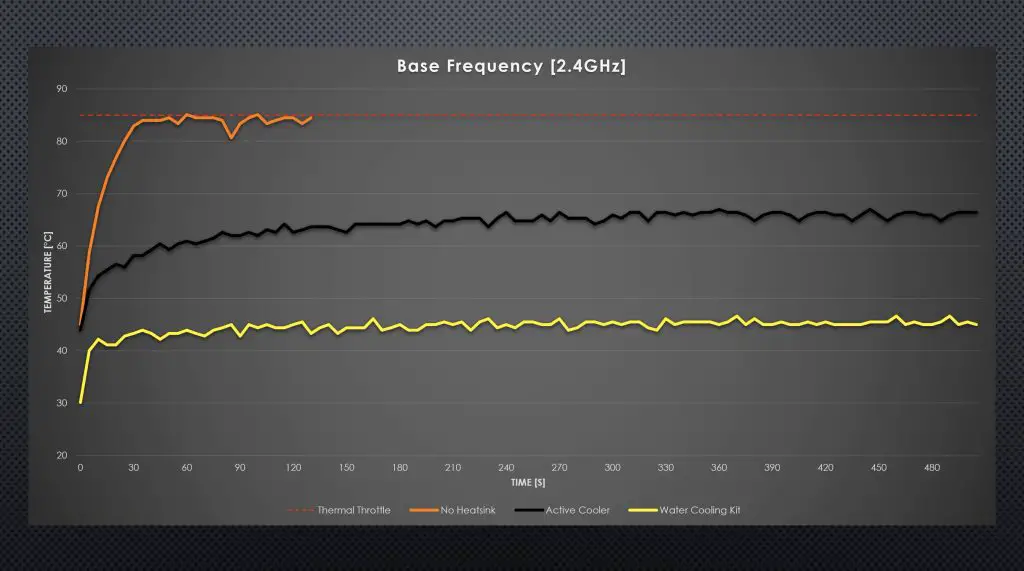

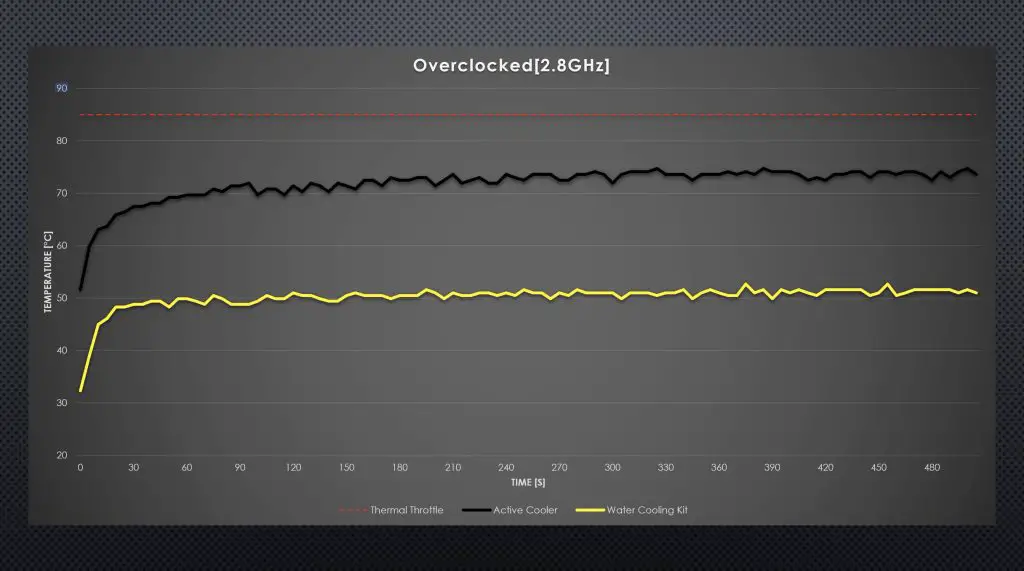

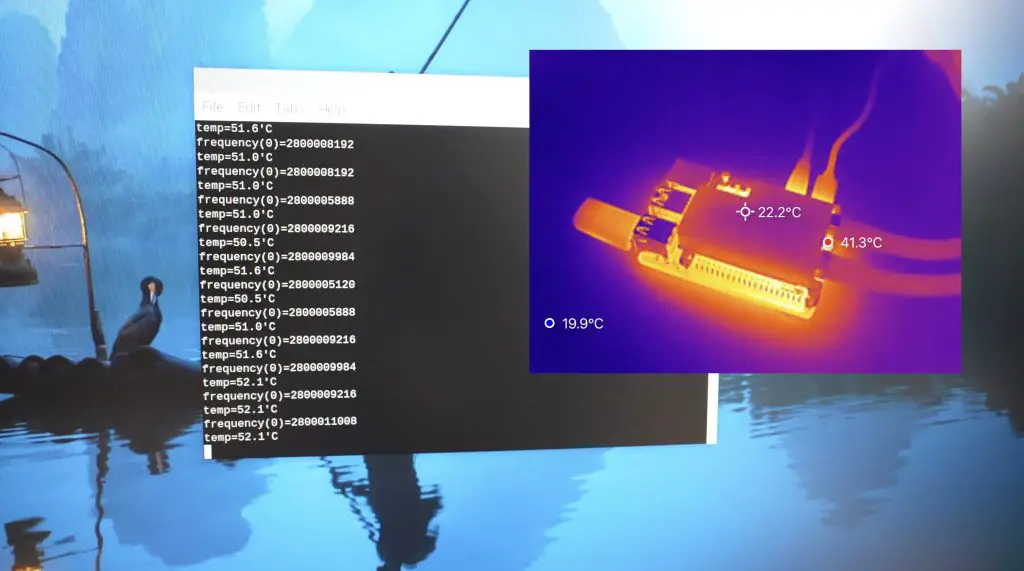

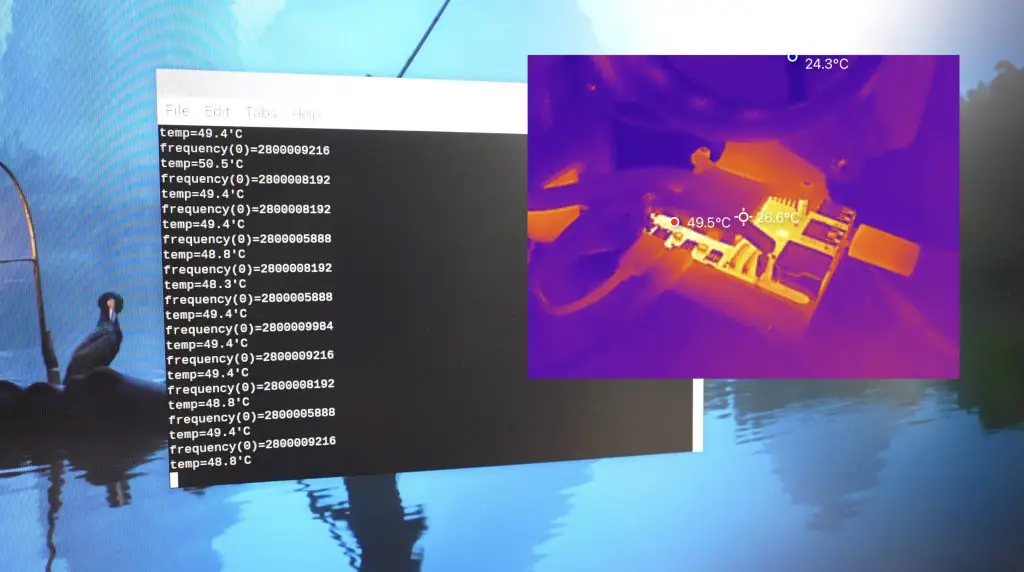

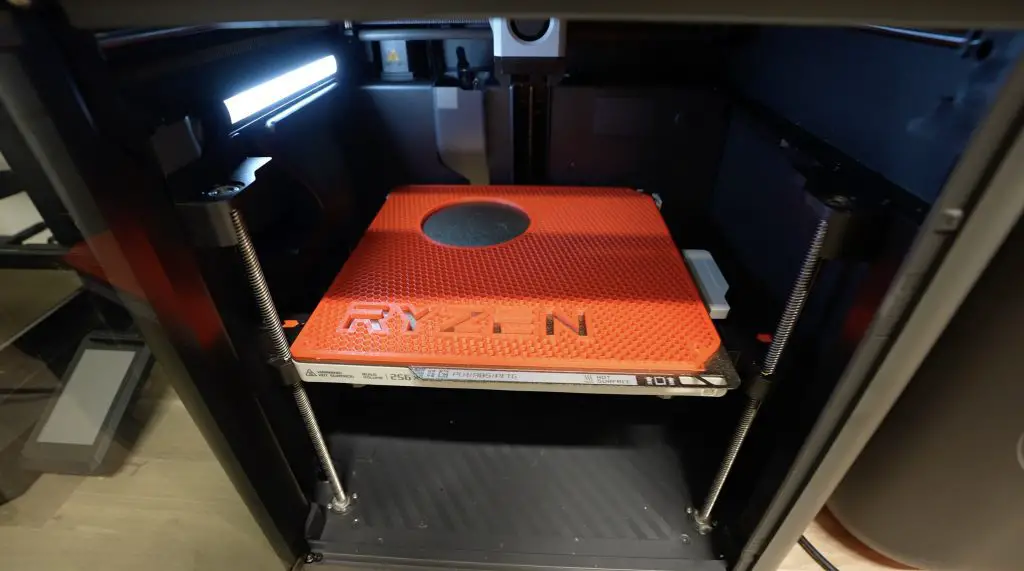

The optional heat sink and fan do a good job at keeping the Core 3588E cool. After 20 minutes of 1080P video playback on YouTube, the CPU was only at 47 degrees and the heatsink was at 38 degrees.

Sysbench CPU Benchmark

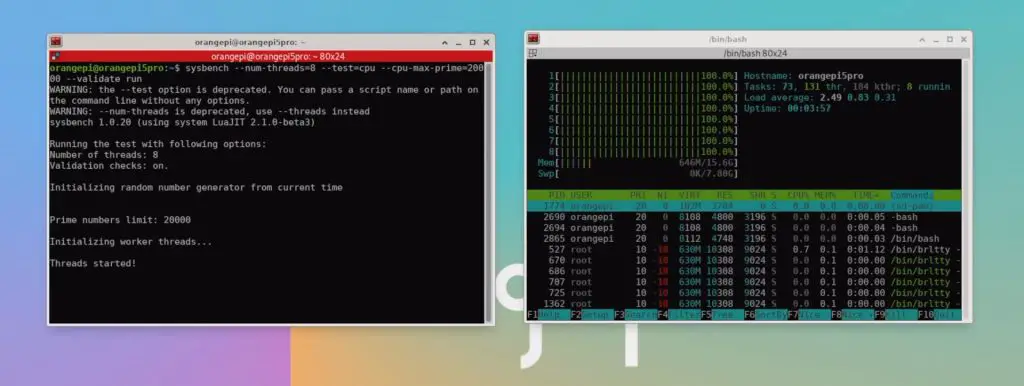

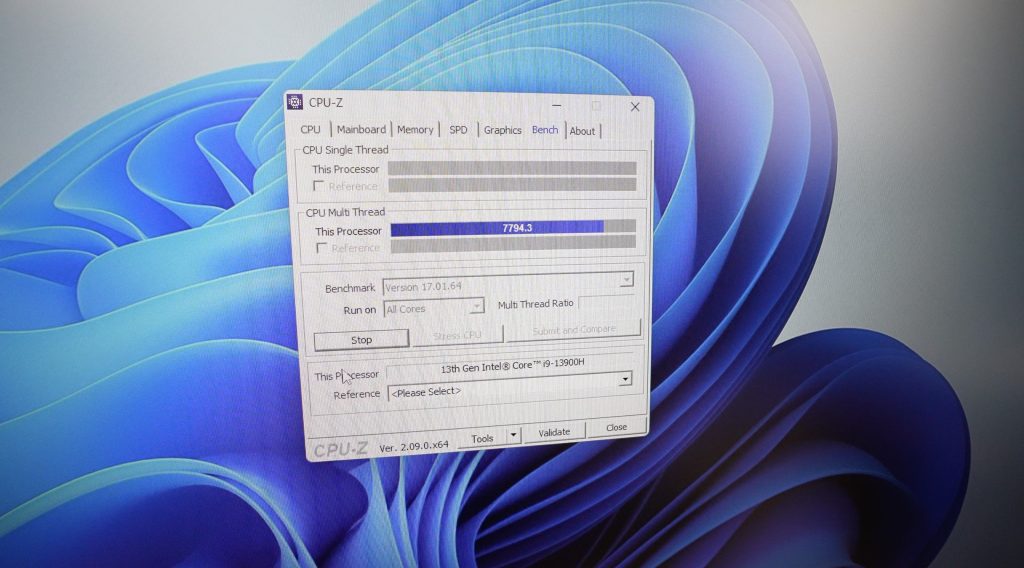

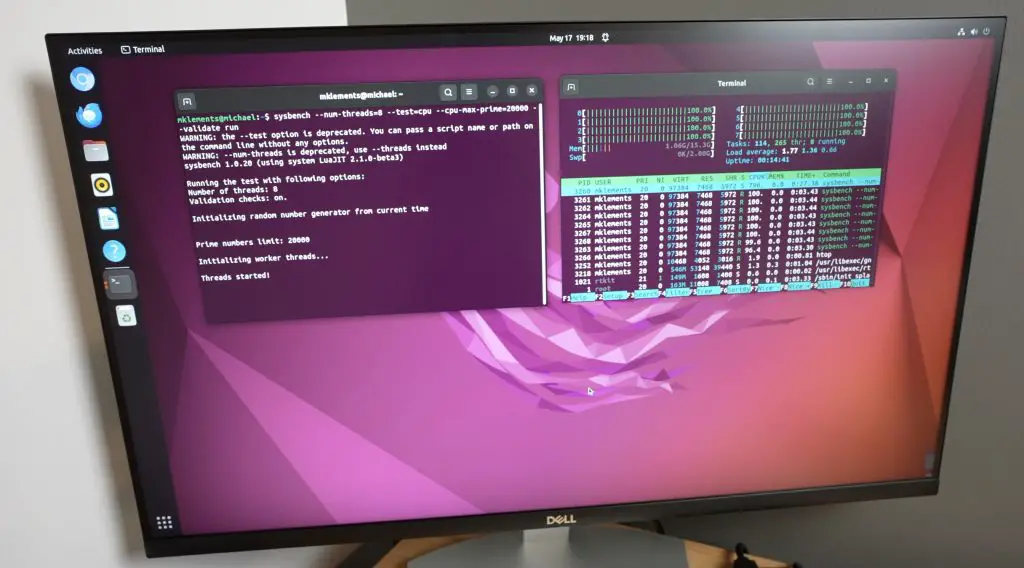

Next let’s do a CPU performance comparison with the Mixtile Blade 3, Rock 5 B and Orange Pi 5 Plus which all run the same RK3588 SOC. We’ll do this by running the Sysbench CPU benchmark.

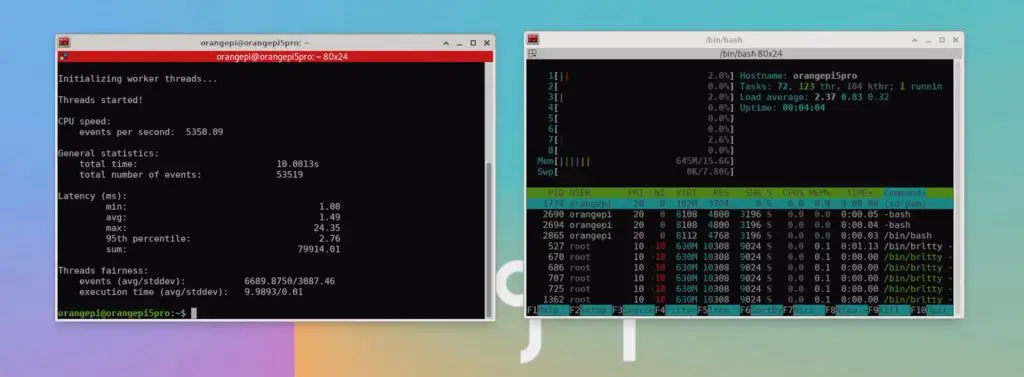

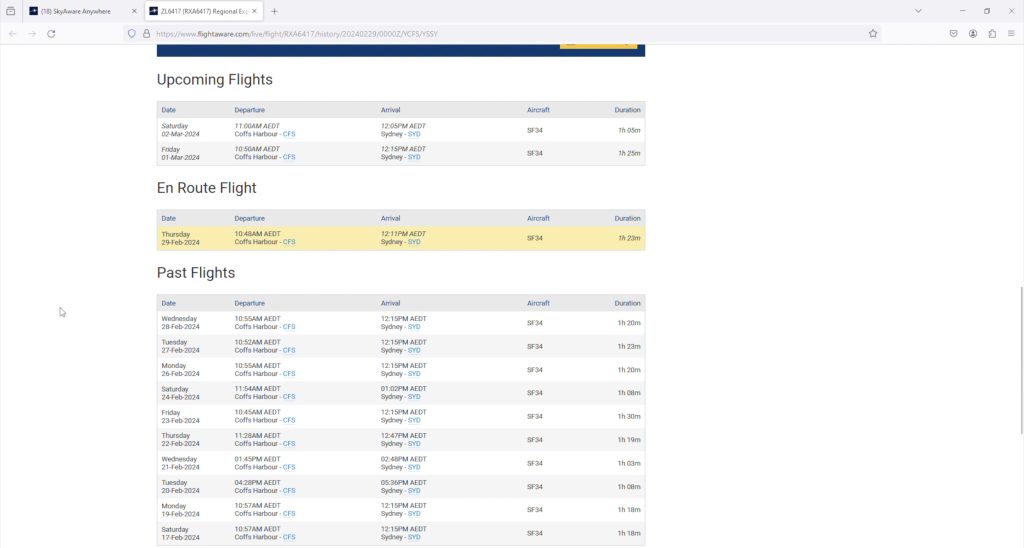

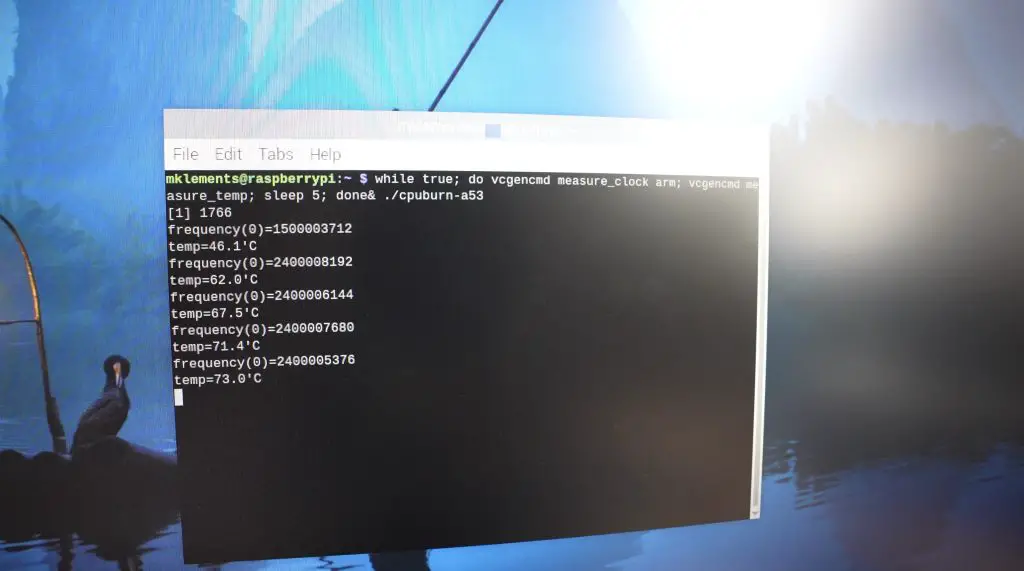

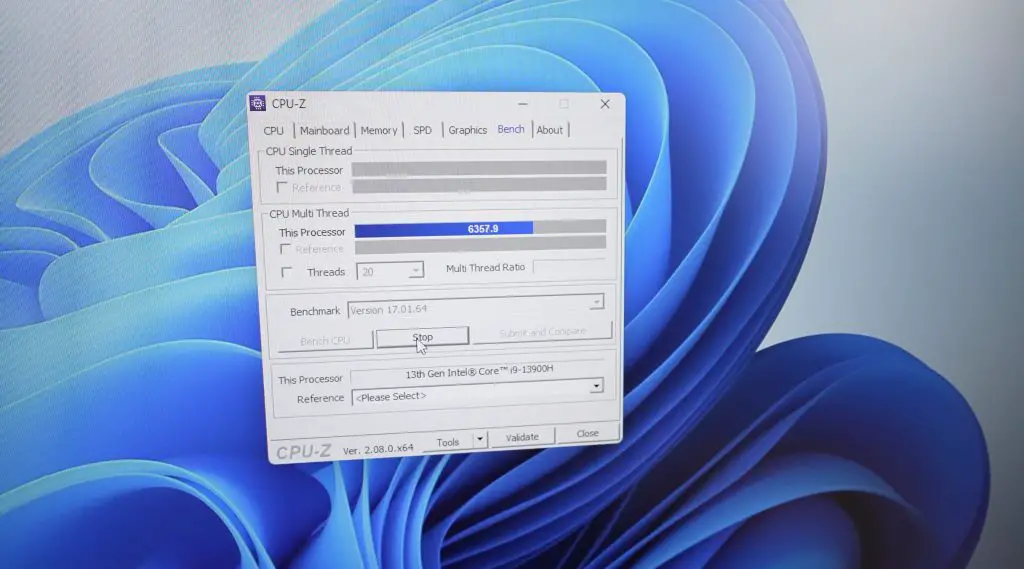

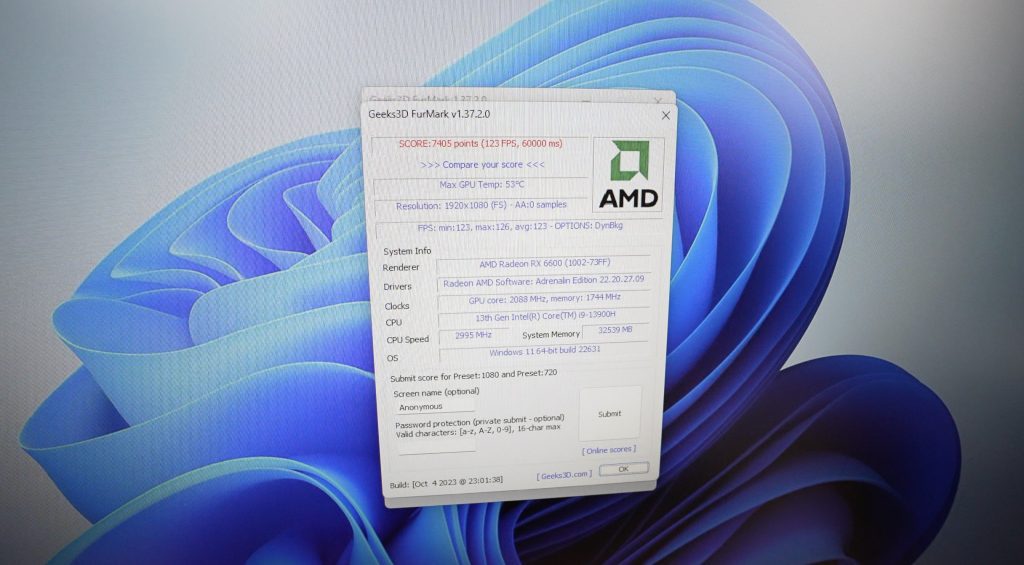

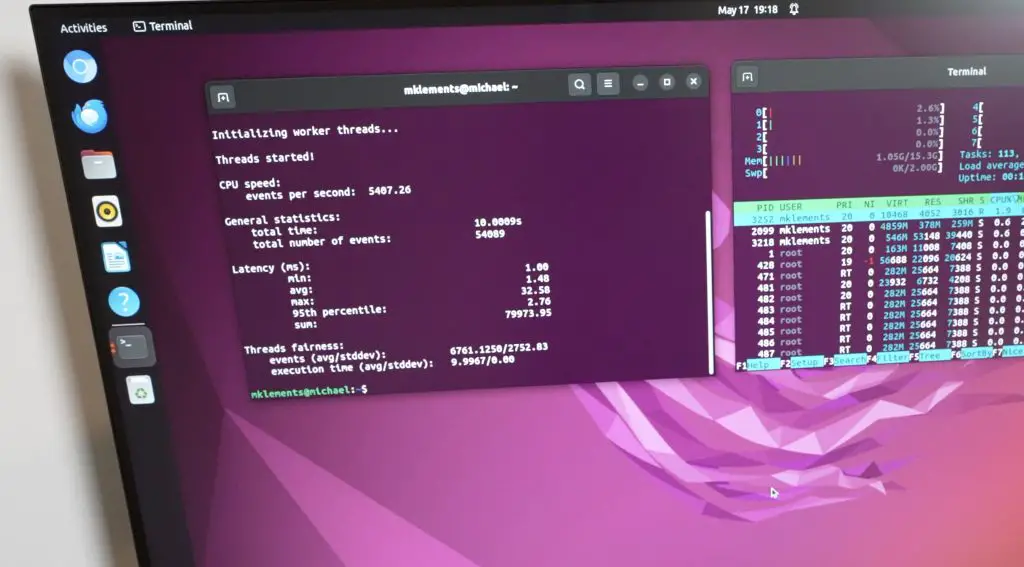

After 10 seconds we have processed a little under 5400 events per seconds and we get a total score of 54,089. Over three tests we get an average score of 54,083.

For comparison, also over three consecutive tests;

- Mixtile Blade 3 managed an average of 54,025

- Rock 5 B managed an average of 53,642

- Orange Pi 5 Plus managed an average of 53,436

So the results from the Core 3588e are slightly higher than the other boards I’ve tested but this is not a significant improvement. It is likely because we’re running a different OS this test was run on Ubuntu and all of the others were tested on Debian.

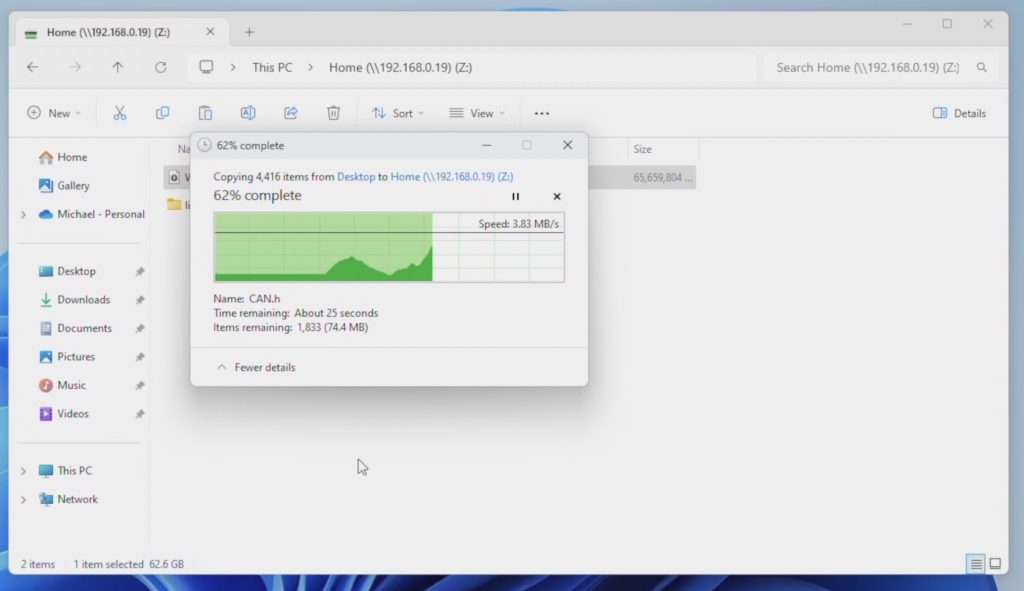

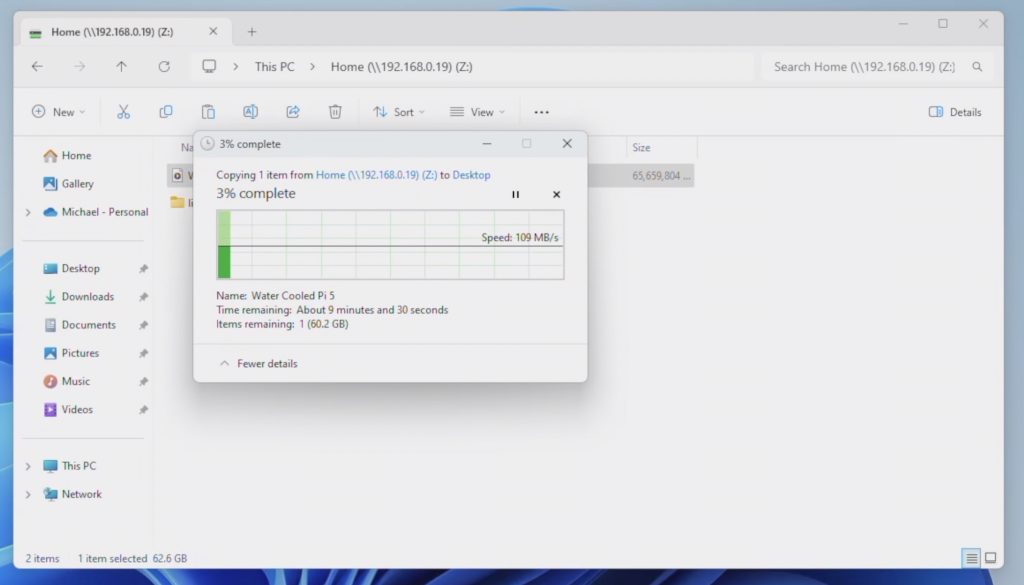

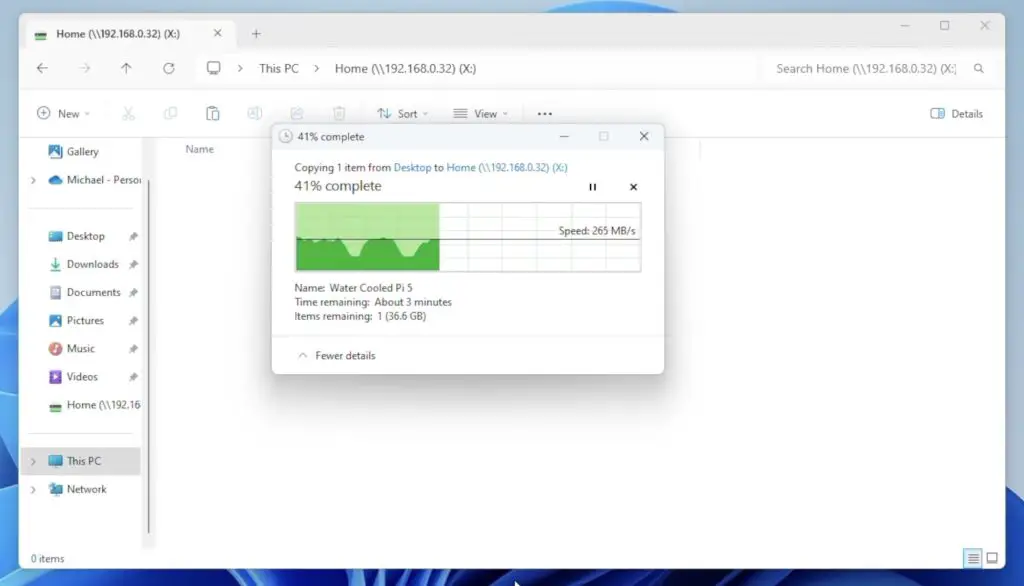

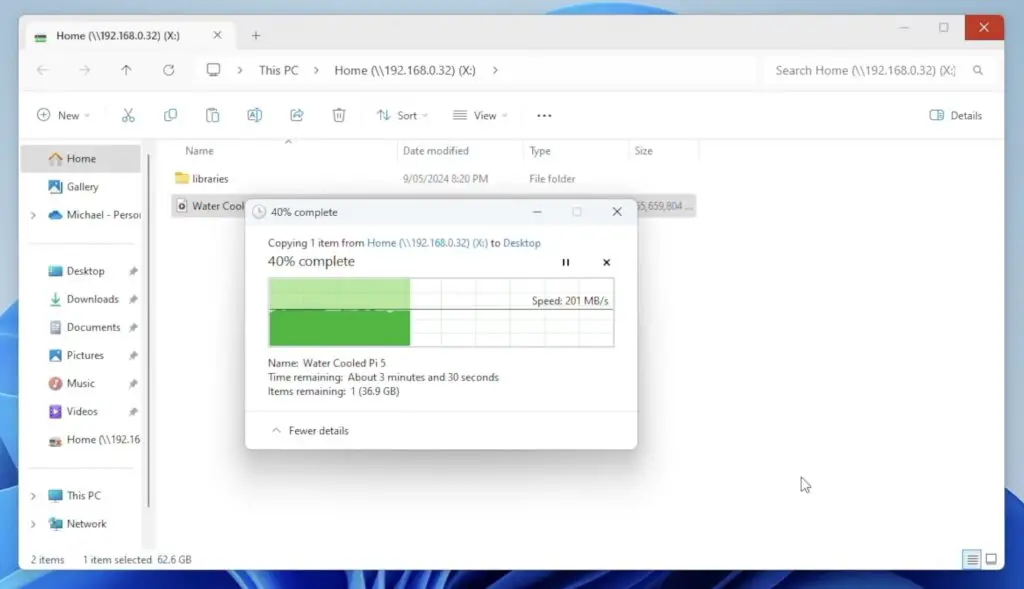

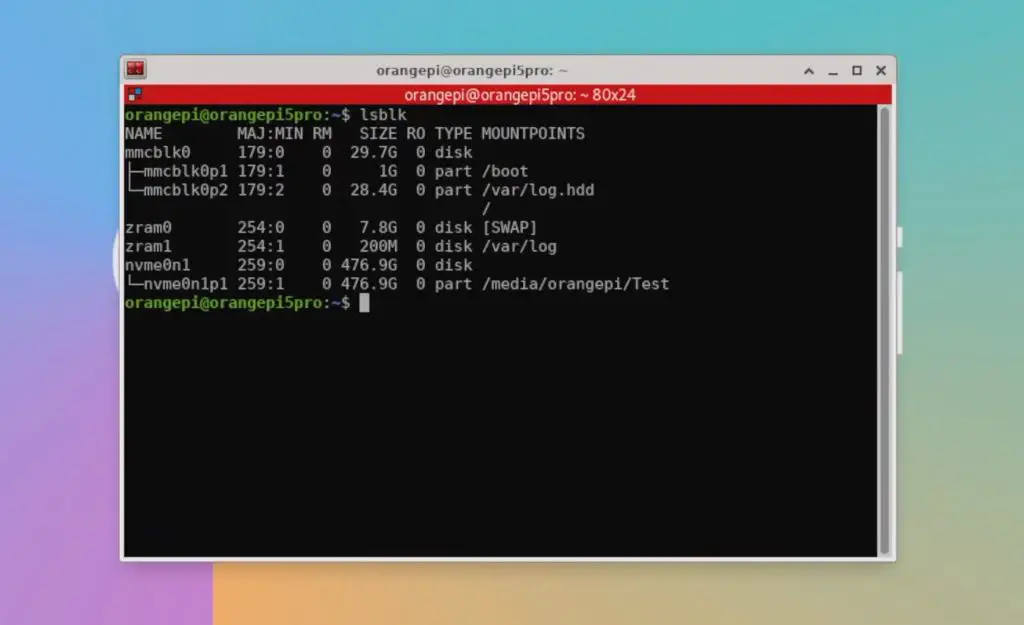

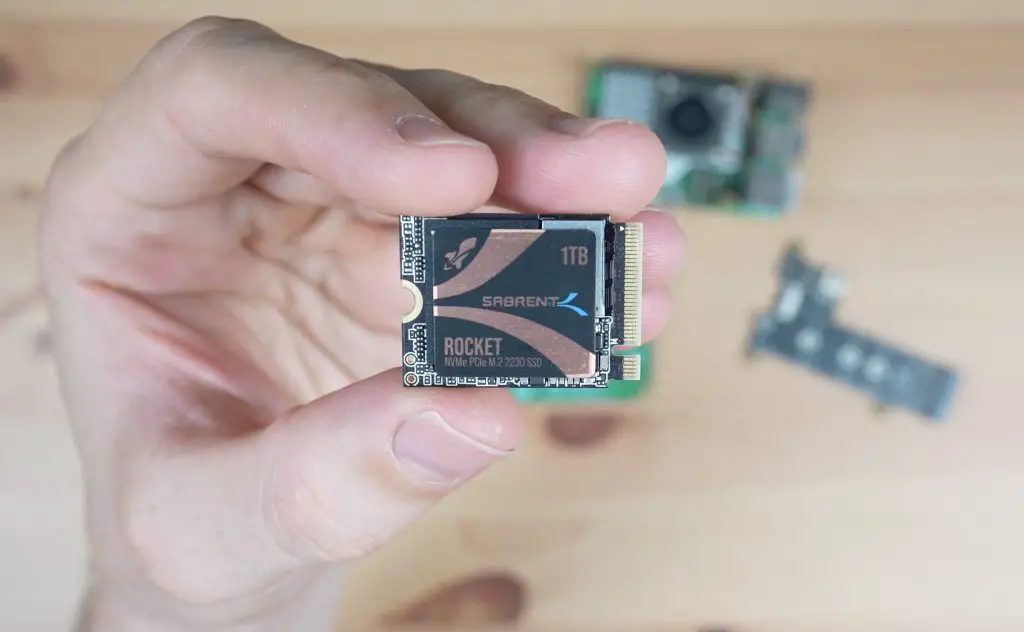

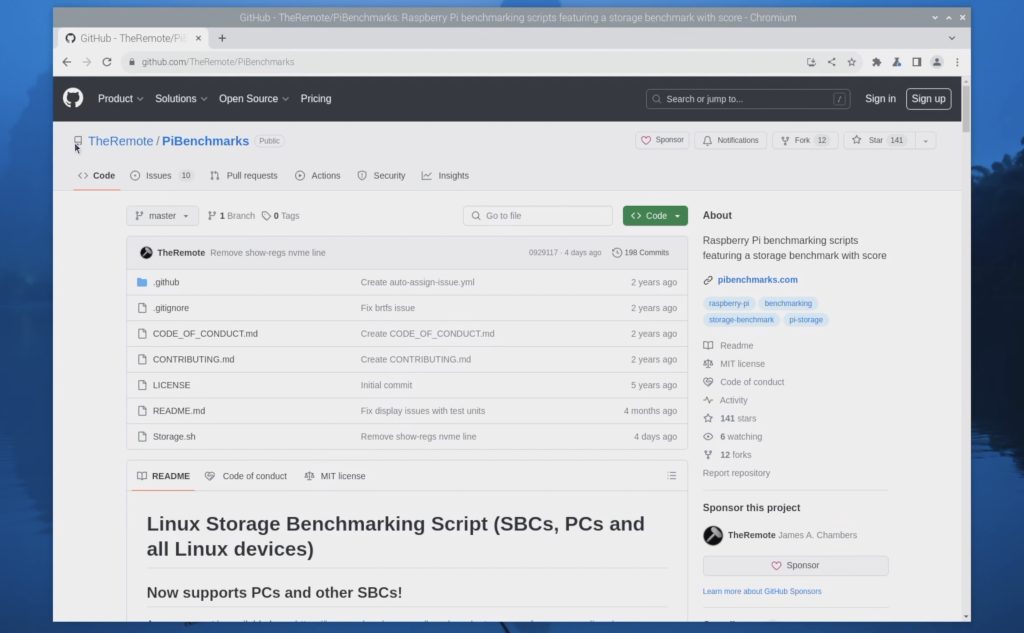

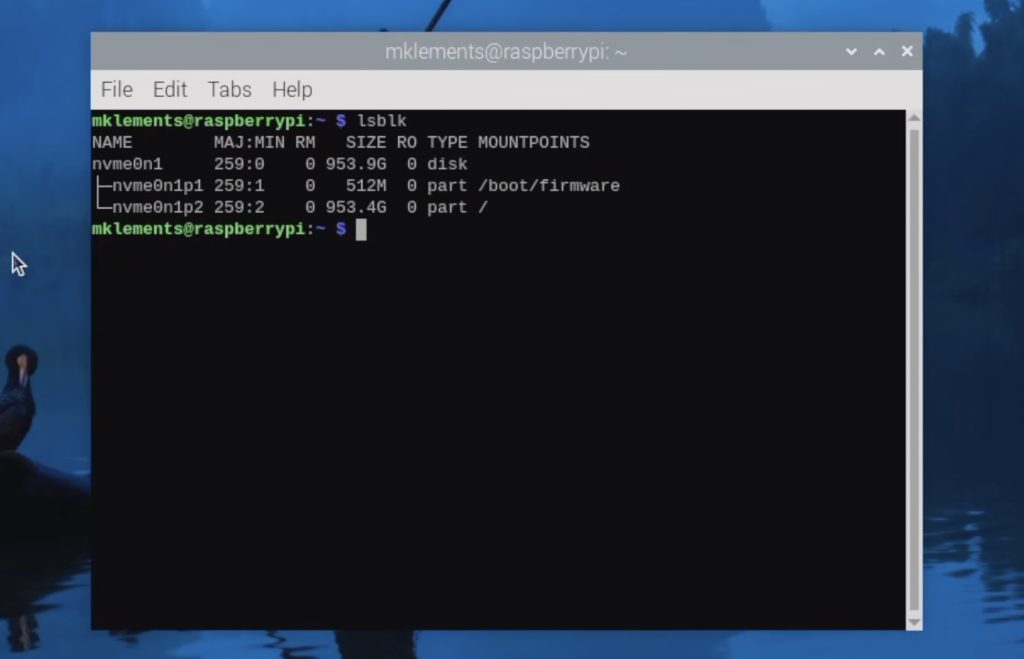

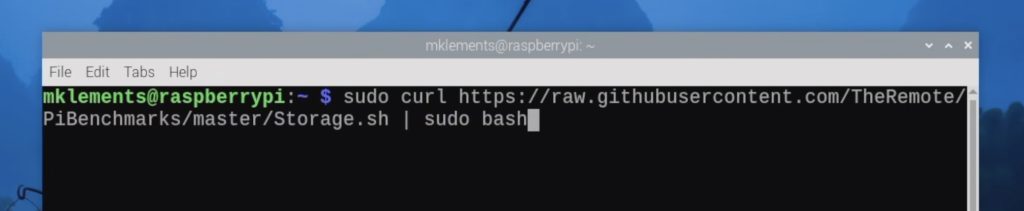

eMMC Storage Benchmark

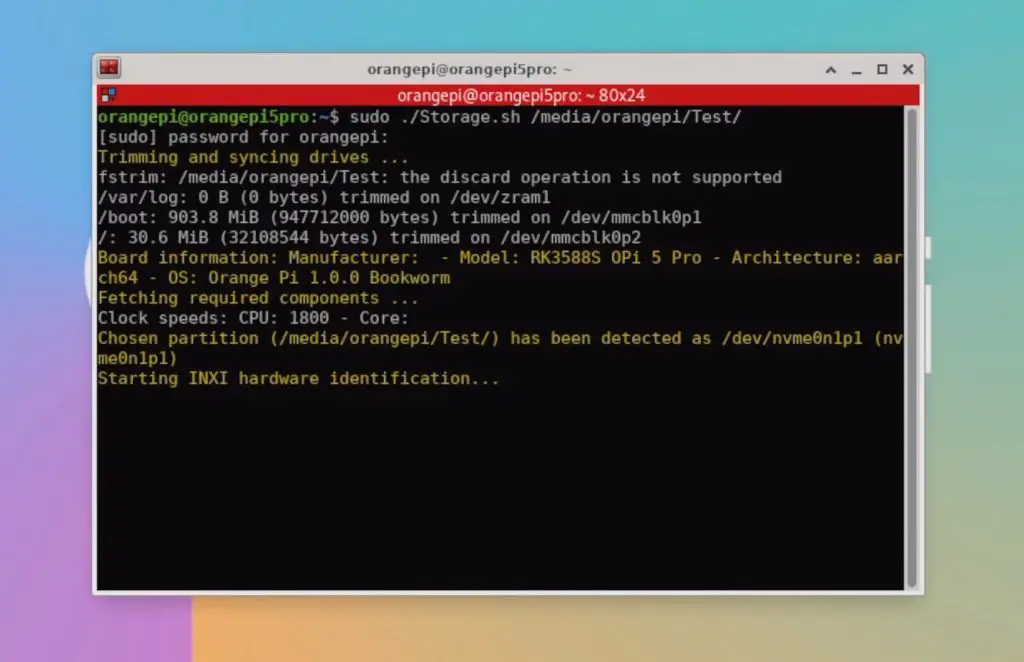

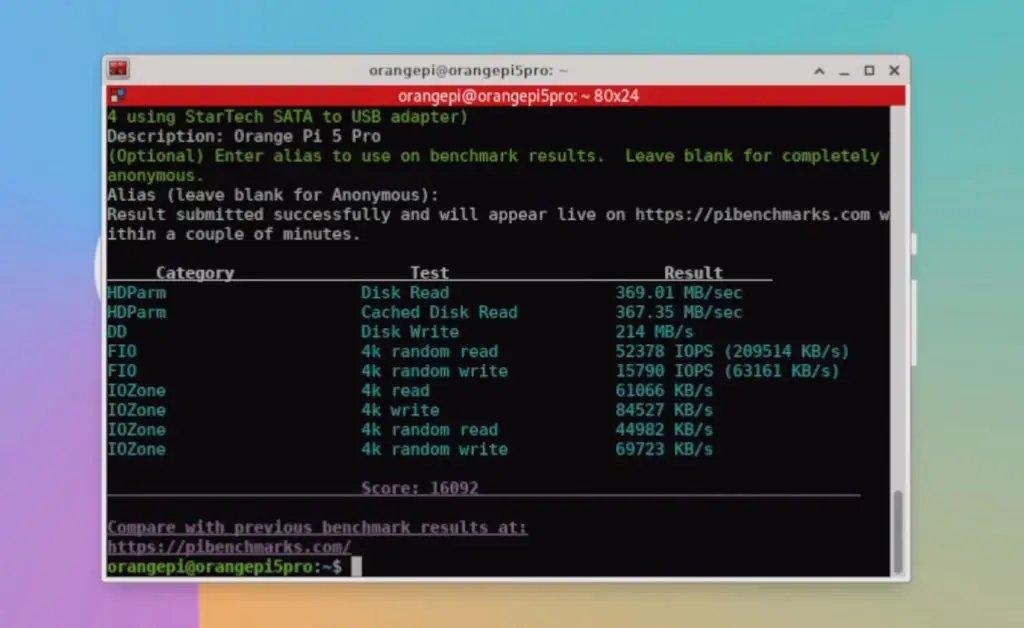

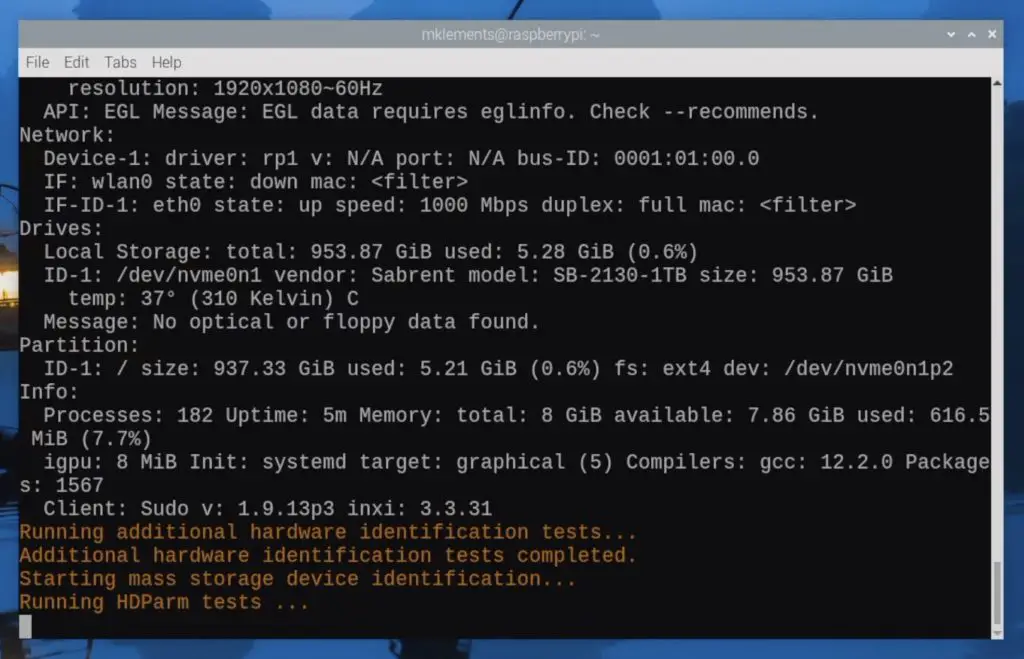

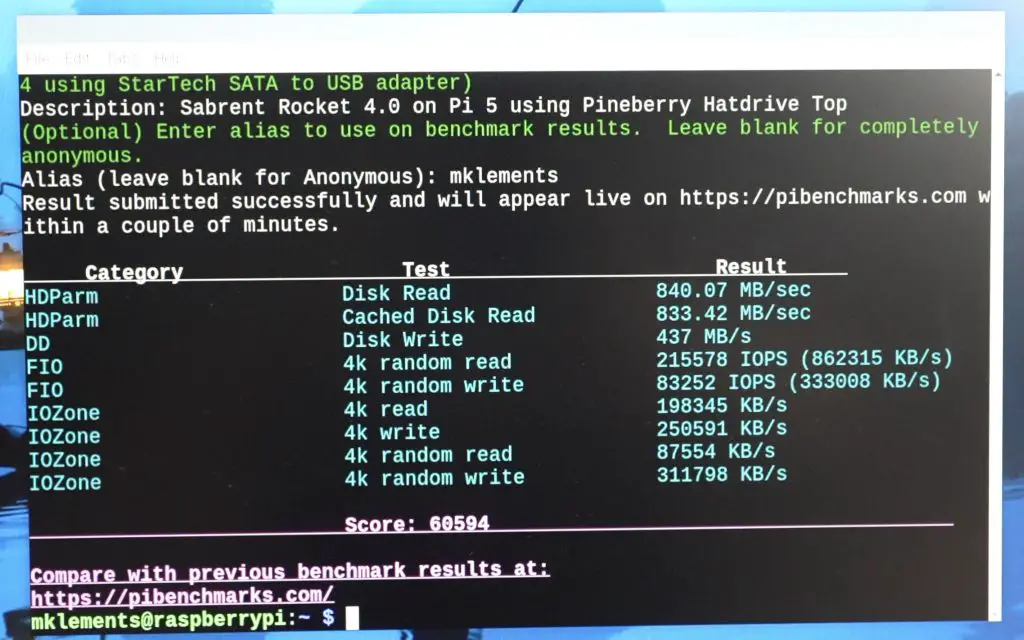

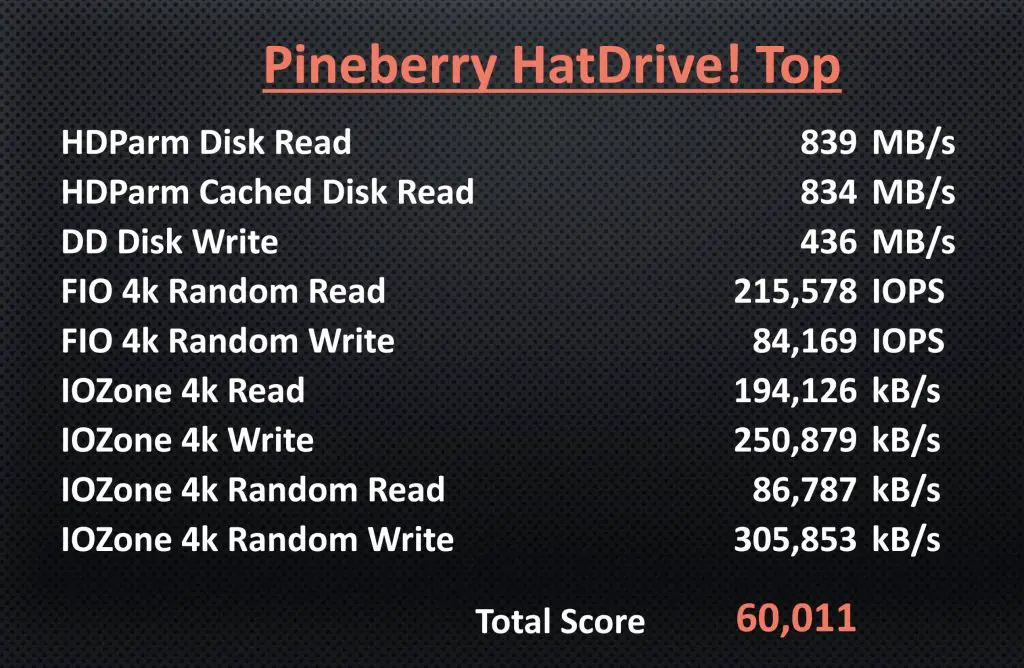

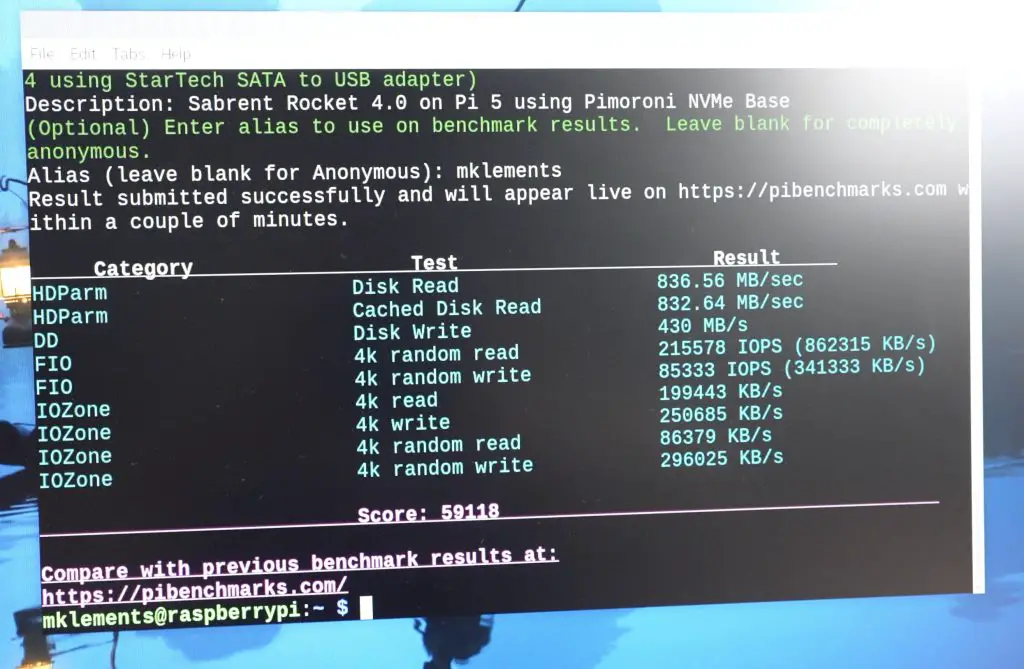

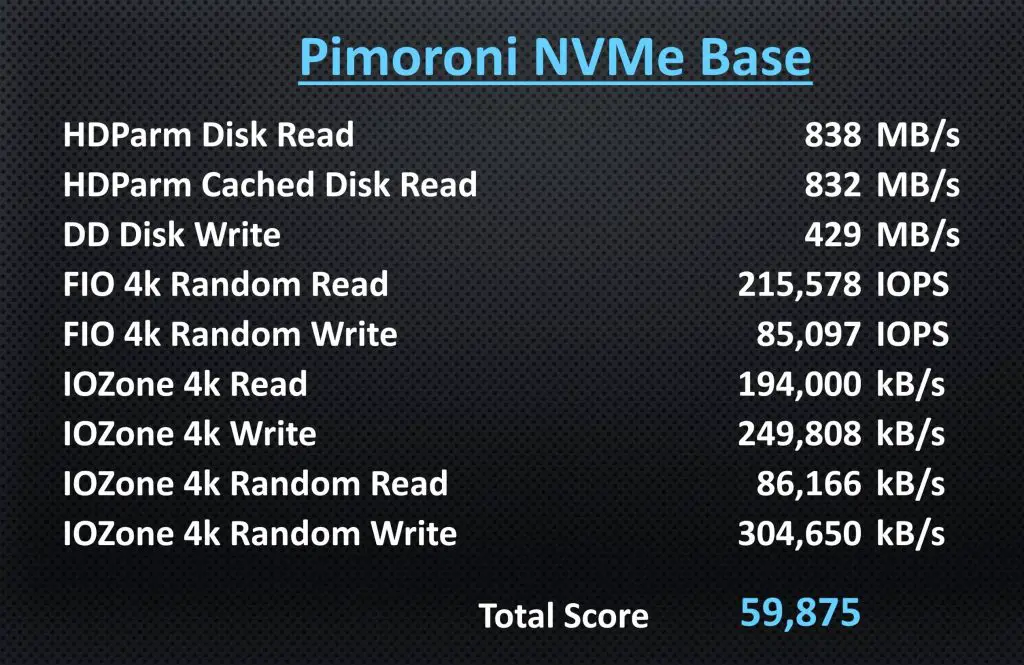

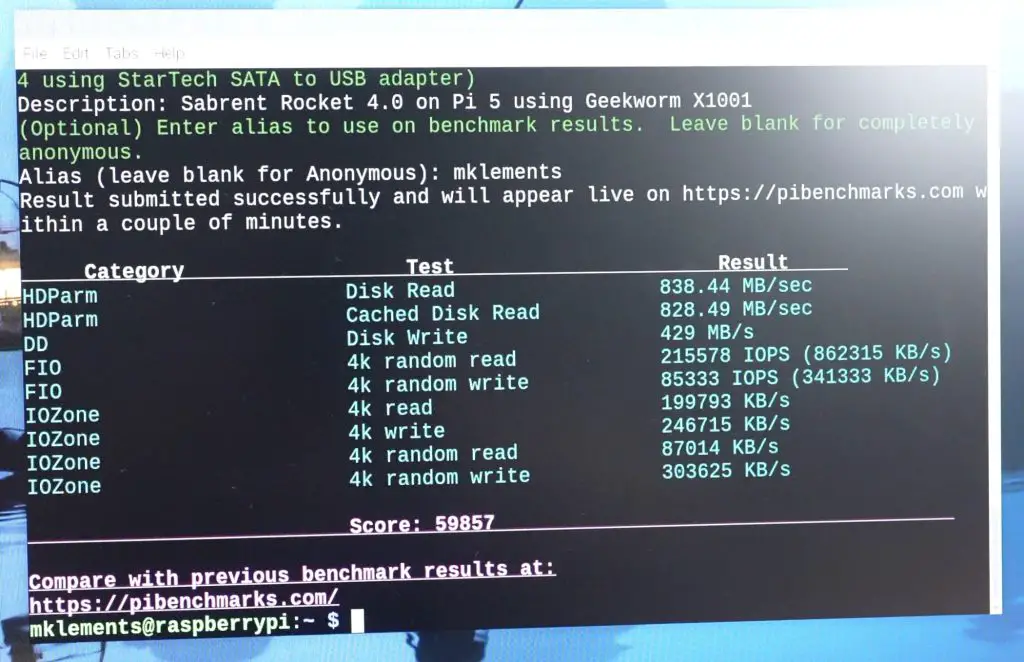

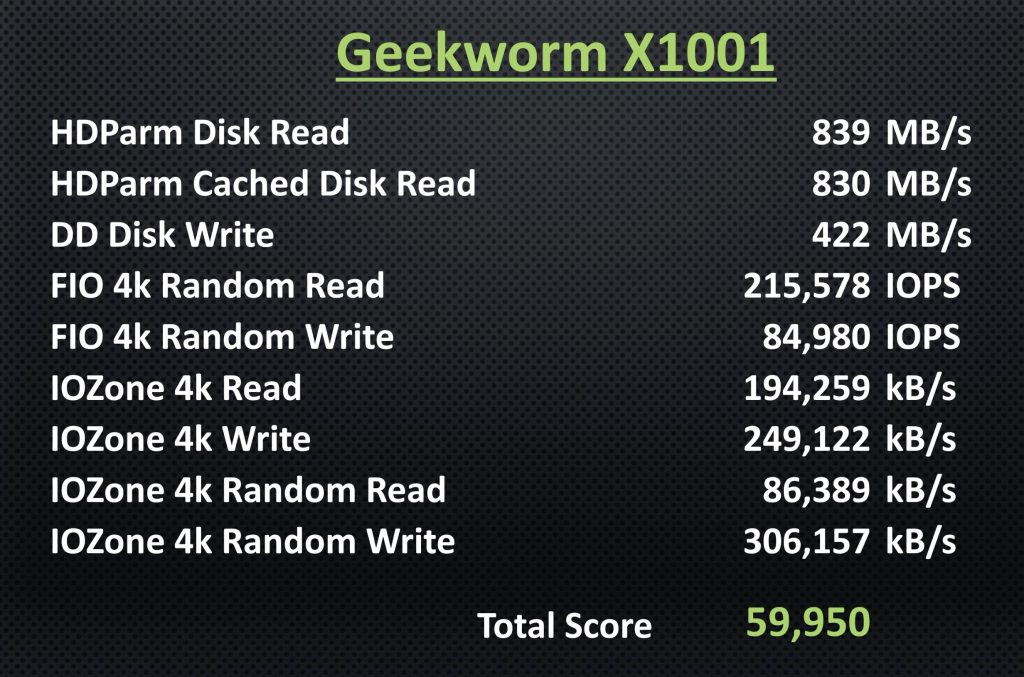

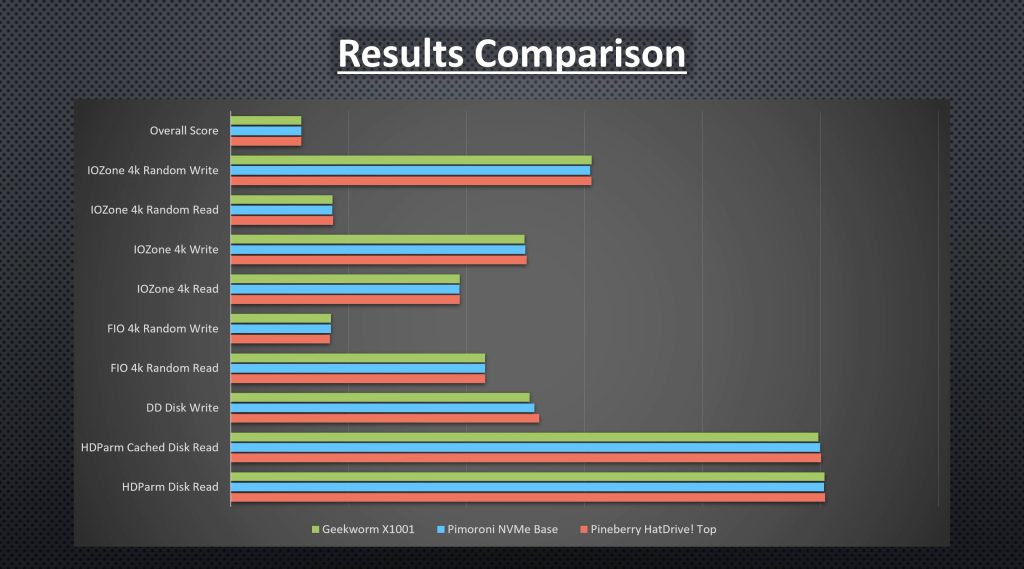

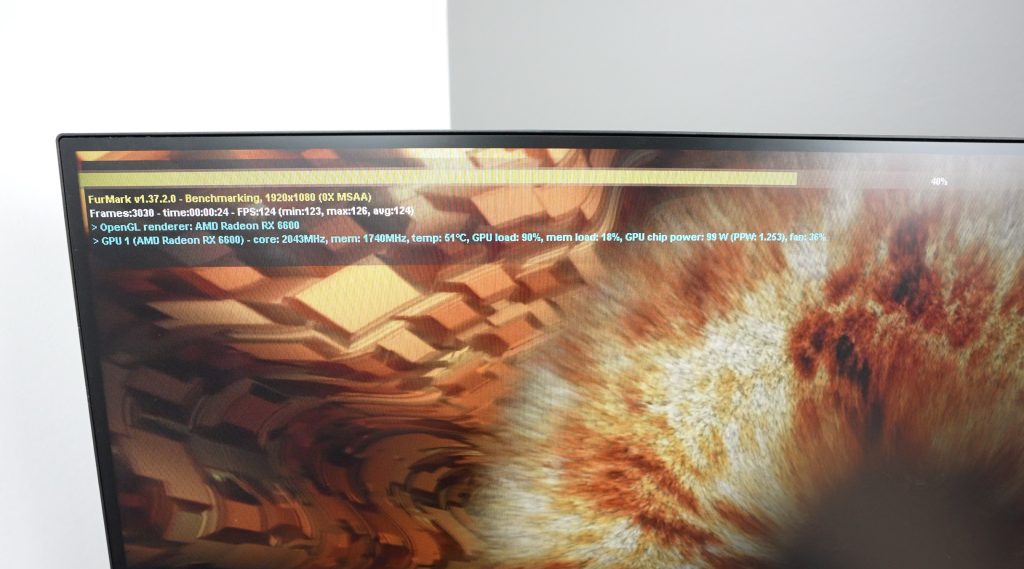

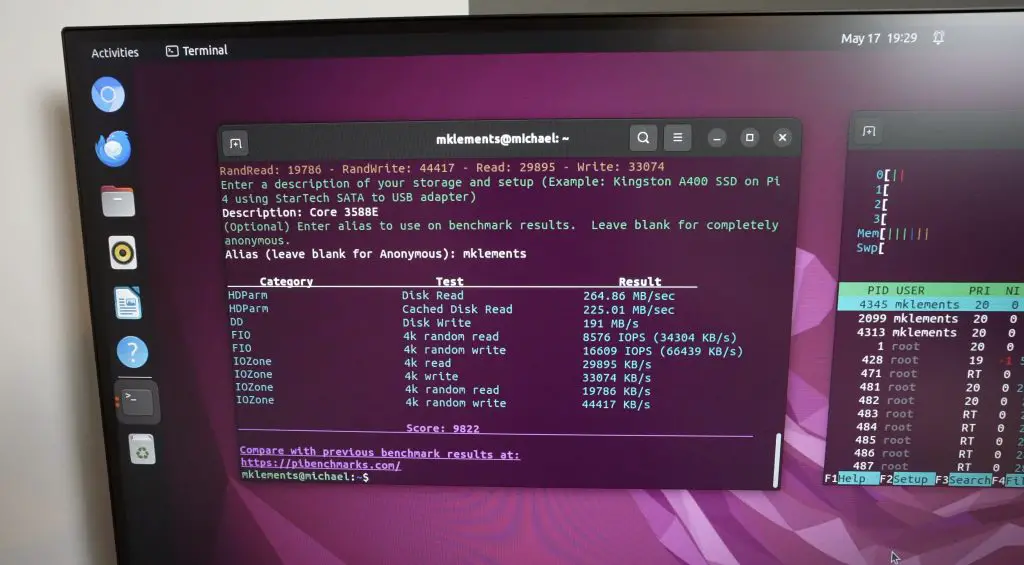

Next, we’ll run James Chamber’s Pi Benchmarks script to test the speed of the onboard eMMC storage. This benchmark favours better random read/write performance because this is a good representation of how the storage or drive would typically be used as an OS drive rather than just reading or writing single large files to it.

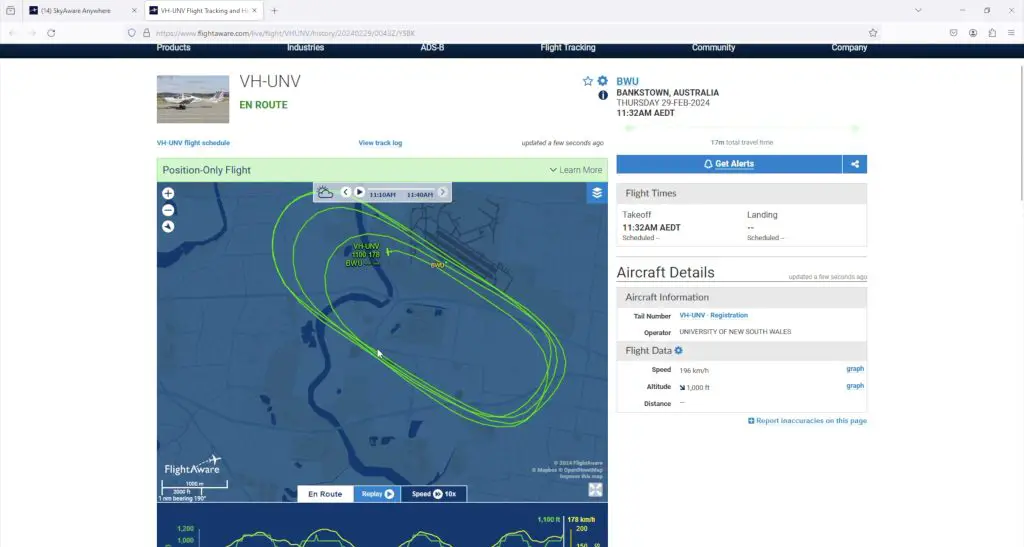

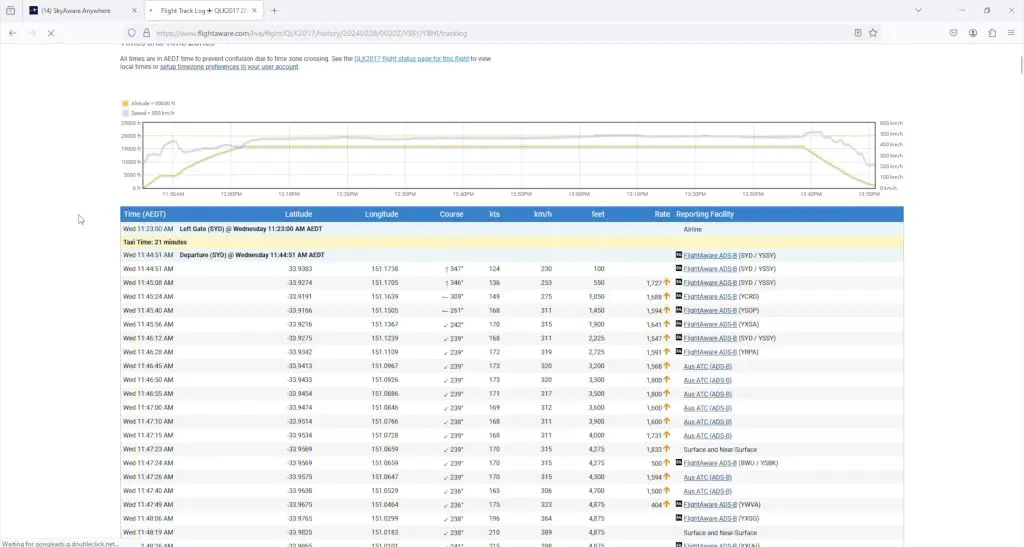

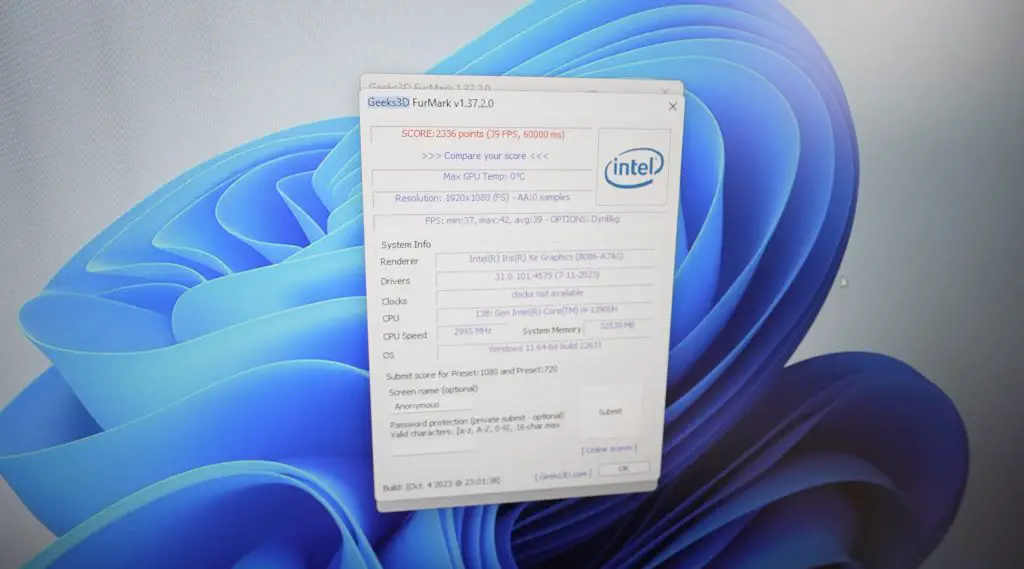

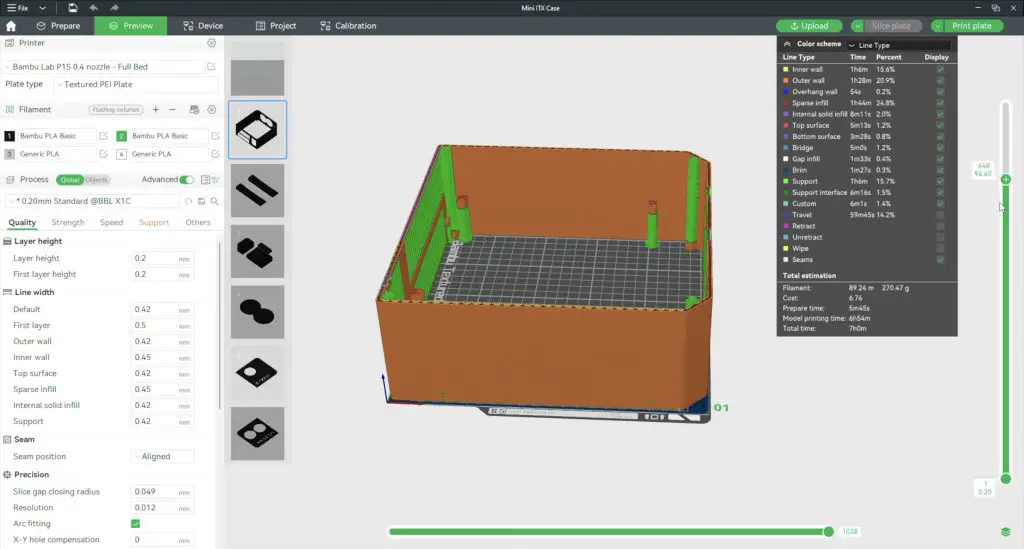

On completion of the test, we get a total score of 9,822. The individual test results are also listed in the image below.

The results aren’t great, sequential read speeds are around 264MB/s and writes are around 225MB/s. Random reads and writes are 13 times and 5 times slower respectively. A better option would probably be to boot from an NVMe drive on the carrier board, but the eMMC storage is ok for an onboard solution if you aren’t transferring large amounts of data.

AI Object Detection Model

Now let’s try an AI object detection model. This is a pre-trained model that you send an image to and it then analyses the image to see if any objects that it has been trained to identify are present.

Here is a list of the objects that the model can detect (each row being a category);

person

bicycle, car, motorbike, aeroplane, bus, train, truck, boat

traffic light, fire hydrant, stop sign, parking meter, bench

cat, dog, horse, sheep, cow, elephant, bear, zebra, giraffe

backpack, umbrella, handbag, tie, suitcase, frisbee, skis, snowboard, sports ball, kite, baseball bat, baseball glove, skateboard, surfboard, tennis racket

bottle, wine glass, cup, fork, knife, spoon, bowl

banana, apple, sandwich, orange, broccoli, carrot, hot dog, pizza, donut, cake

chair, sofa, pottedplant, bed, diningtable, toilet, tvmonitor, laptop, mouse, remote, keyboard, cell phone, microwave, oven, toaster, sink, refrigerator, book, clock, vase, scissors, teddy bear, hair drier, toothbrushWe need to run the below commands to download the code, install the dependencies and build the YOLOV5 demo code;

sudo apt install cmake

git clone https://github.com/rockchip-linux/rknpu2

cd rknpu2/examples/rknn_yolov5_demo/

./build-linux_RK3588.shOnce installed, the model can be run using the below commands;

pushd /home/"Username"/rknpu2/examples/rknn_yolov5_demo/install/rknn_yolov5_demo_Linux/

./rknn_yolov5_demo ./model/RK3588/yolov5s-640-640.rknn "Image Name".jpgI’ve got five test images prepared. We’ll try to put each of these through the model and it’ll produce an output image that shows any detected objects and the model’s confidence in its classifications.

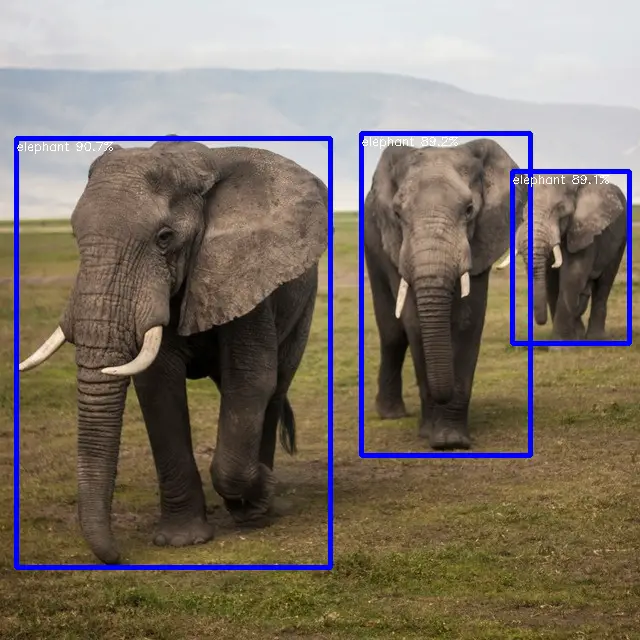

Image 1 is a photograph of 3 elephants;

The image took 18 ms to process, which is impressively fast. It would be able to process around 55 frames per second at this speed.

And this is the result. It got all three correct with a fairly high level of confidence.

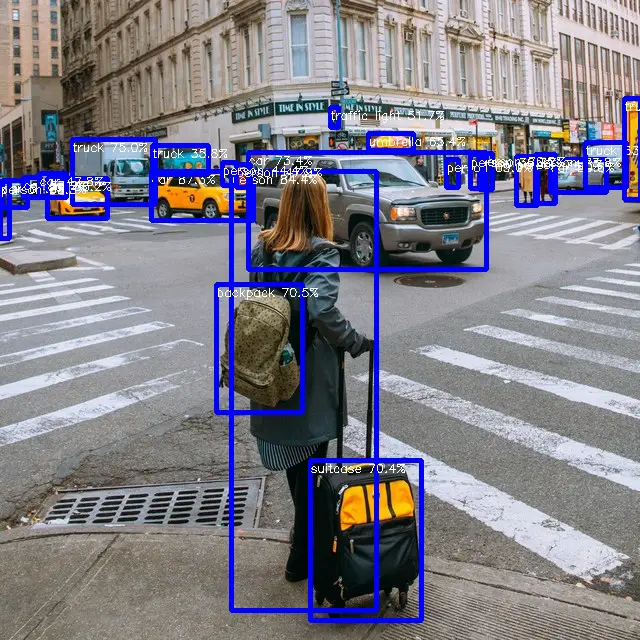

Image 2 is a woman in front of a pedestrian crossing with some traffic in the background.

This too took 18 ms to process and the results are pretty good. There is a lot going on in the background but the main elements in the foreground and centre are all correct. Even some of the more obscure background objects are correct.

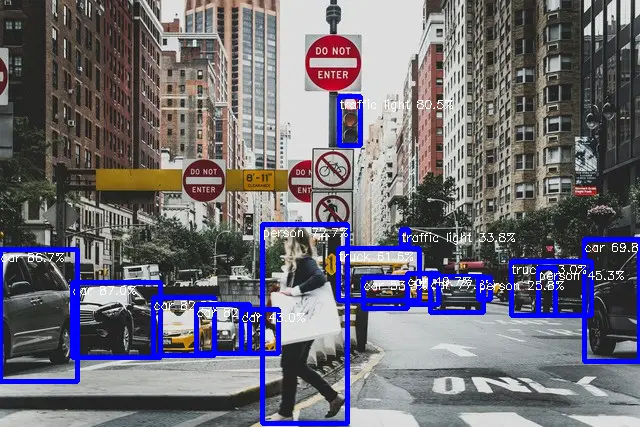

Image 3 is a similar traffic image.

This has got most of the main elements correct and even a number of the partially obscured cars are correctly identified.

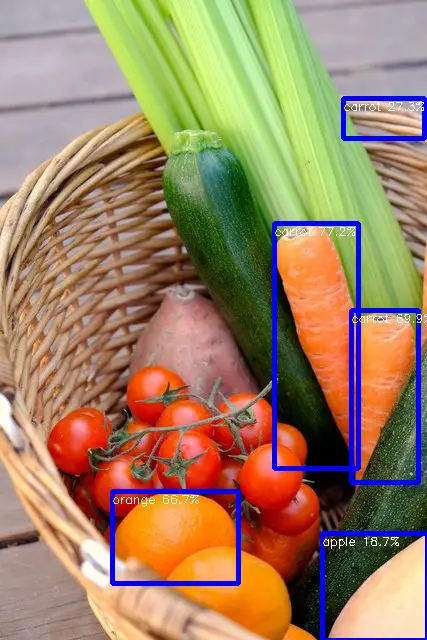

Image 4 is a basket of vegetables with some oranges in front of them.

It made a few mistakes here. I’m not even sure why – these look nothing like an apple or carrot. The confidence levels are pretty low so it clearly had trouble working through these areas.

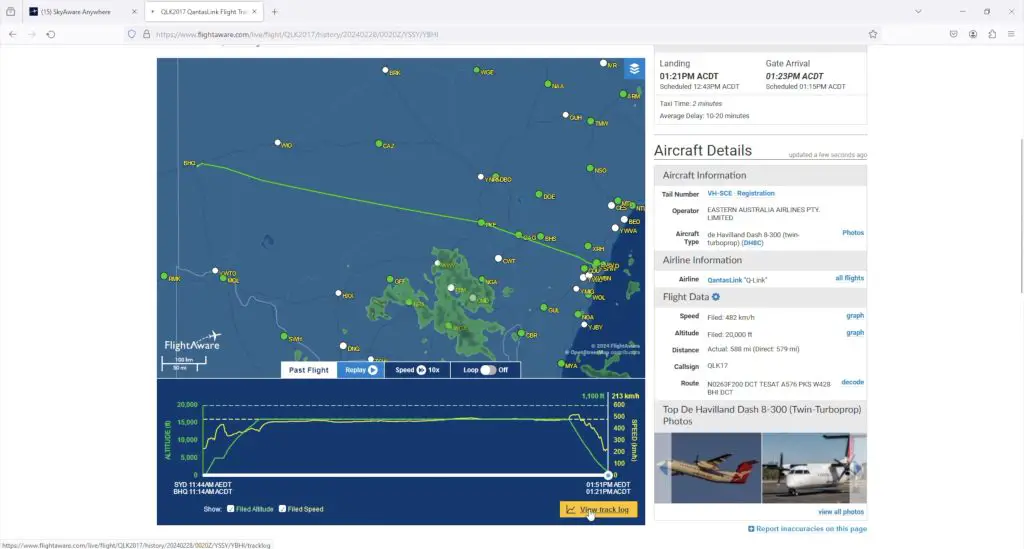

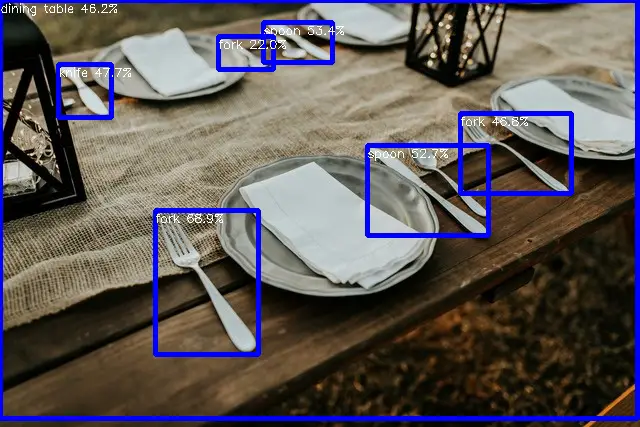

The last image is a dinner table.

Again this image is mostly correct, even recognising that the whole image is of a dinner table. The knives on either side have been missed and have jointly been labelled a spoon with the spoons next to them. The fork on the far side it got right despite the low confidence.

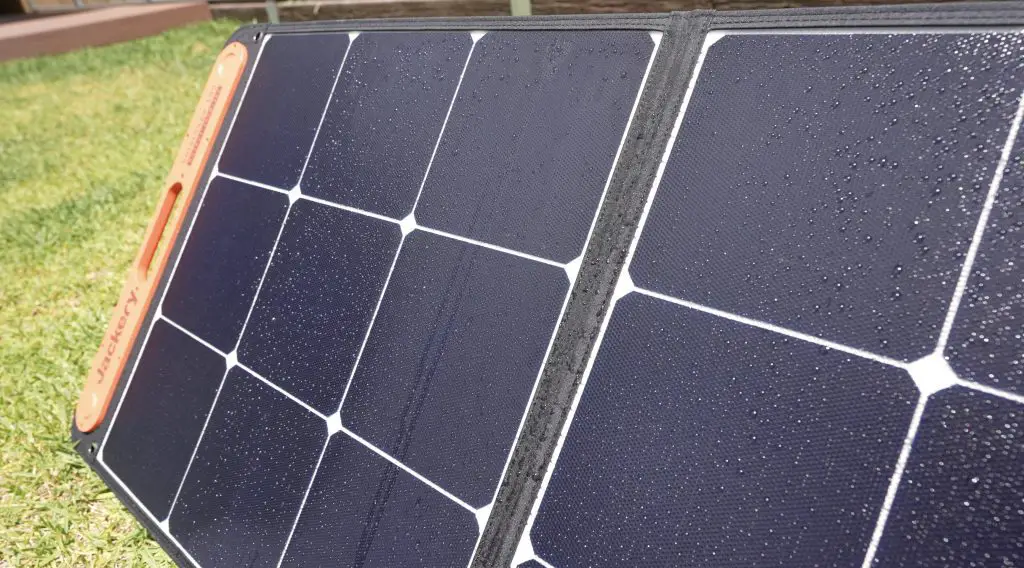

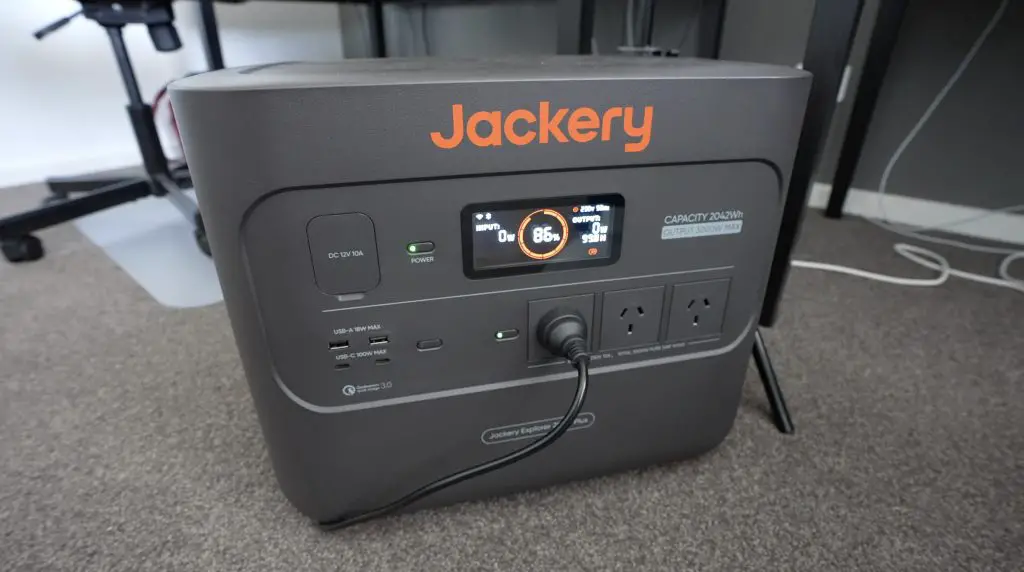

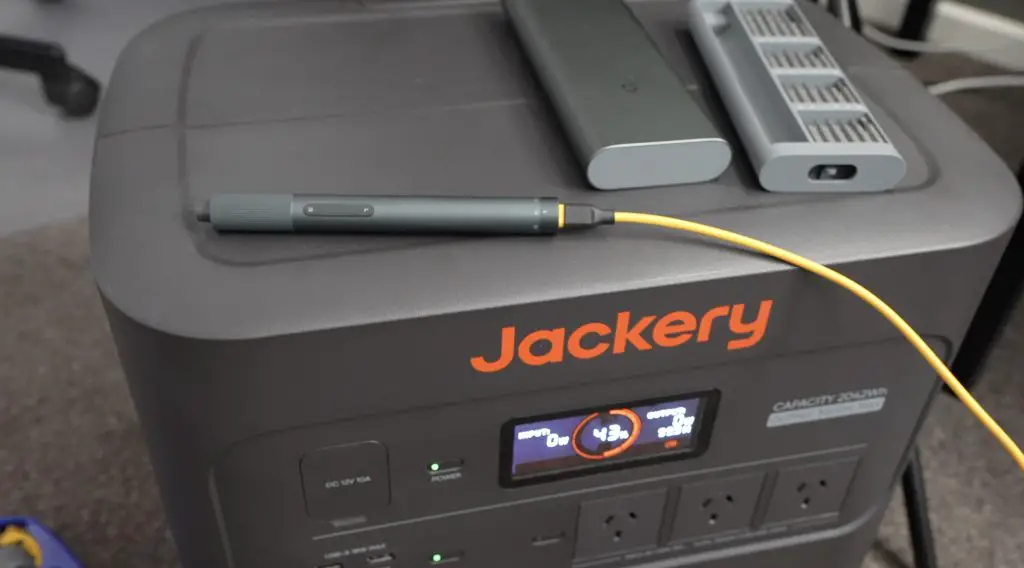

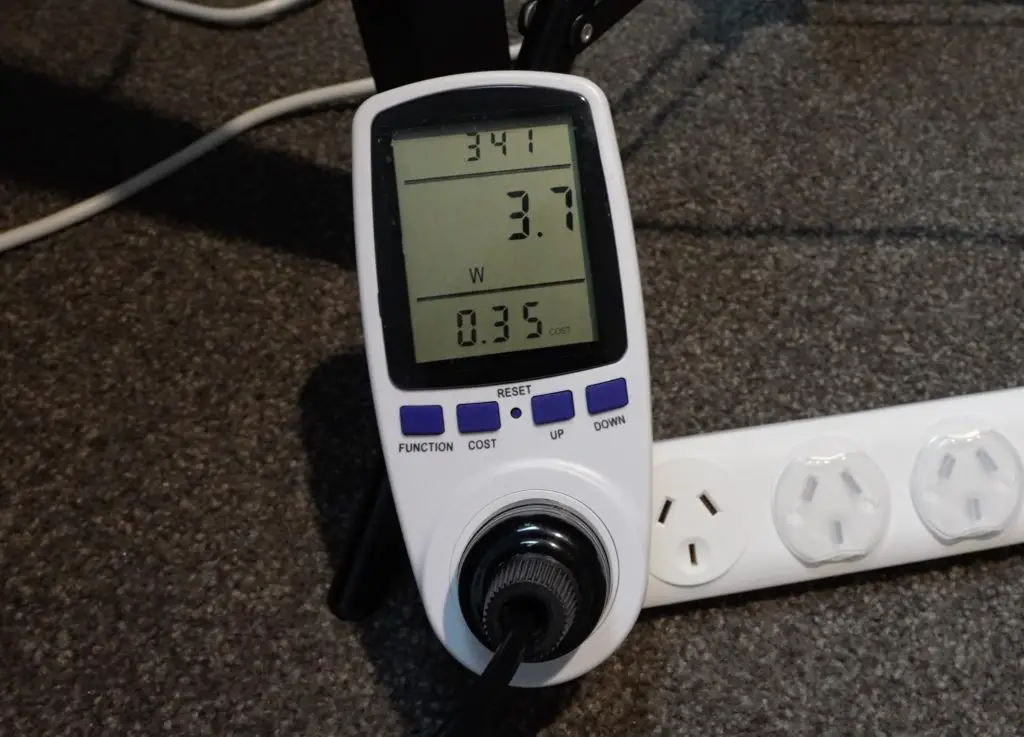

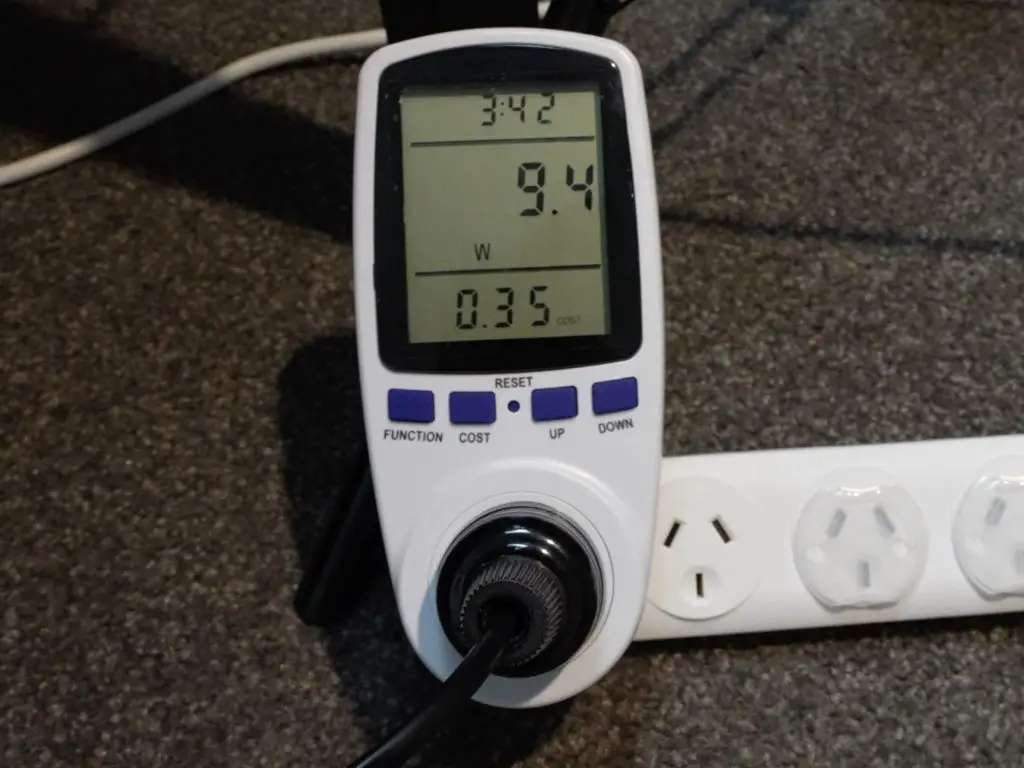

Power Consumption

Lastly, let’s take a look at power consumption. To measure the Core 3588E’s power consumption, I used a mains power meter. This indicates that the Core 3588E uses about 4W when idle and this goes up to 9W when loaded.

This is a bit higher than the Blade 3 but it does have an active cooler on it and a few extra circuits on the carrier board as well, so is expected but still quite power efficient.

Final Thoughts On The Mixtile Core 3588E

Overall I think that, similar to the Blade 3, the Core 3588E is quite expensive, especially considering it is a bare module and you’d still need to add a carrier board or have a device to plug it into to use it. They have again used good quality components, so you should get good reliability and life out of it, and the module is similarly priced to some alternatives like the Turing RK1 modules.

With the RK3588 SOC, performance is really good, especially considering its low power consumption. This module is ideal for applications like live object detection or motion tracking on a video feed.

Let me know what you think of the Mixtile Core 3588E in the comments section below and if there is anything else that you’d like me to try on it.